As Boris Johnson is fond of reminding people (at least when it suits him), Britain is a freedom-loving land; its people tenacious in their defence of fundamental rights.

As was witnessed most recently at the vigil for Sarah Everard, Britons are prepared to challenge the authorities if they feel the cause is right and urgent, and they will not be silenced. You wonder, then, why the government is persisting with the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, which will make the business of protest more difficult – both for those who wish to take to the streets, and for the police who will have to persuade demonstrators to leave the streets.

At the moment, things are made all the more difficult by the current Covid restrictions, which clash badly with sections of the 1998 Human Rights Act, as well as the UK’s international commitments to the right to free speech and free assembly. Asking the police to enforce the law is one thing, but asking them to choose to safeguard one law (the Covid regulations) over others (human rights and common law) is unreasonable.

Read more:

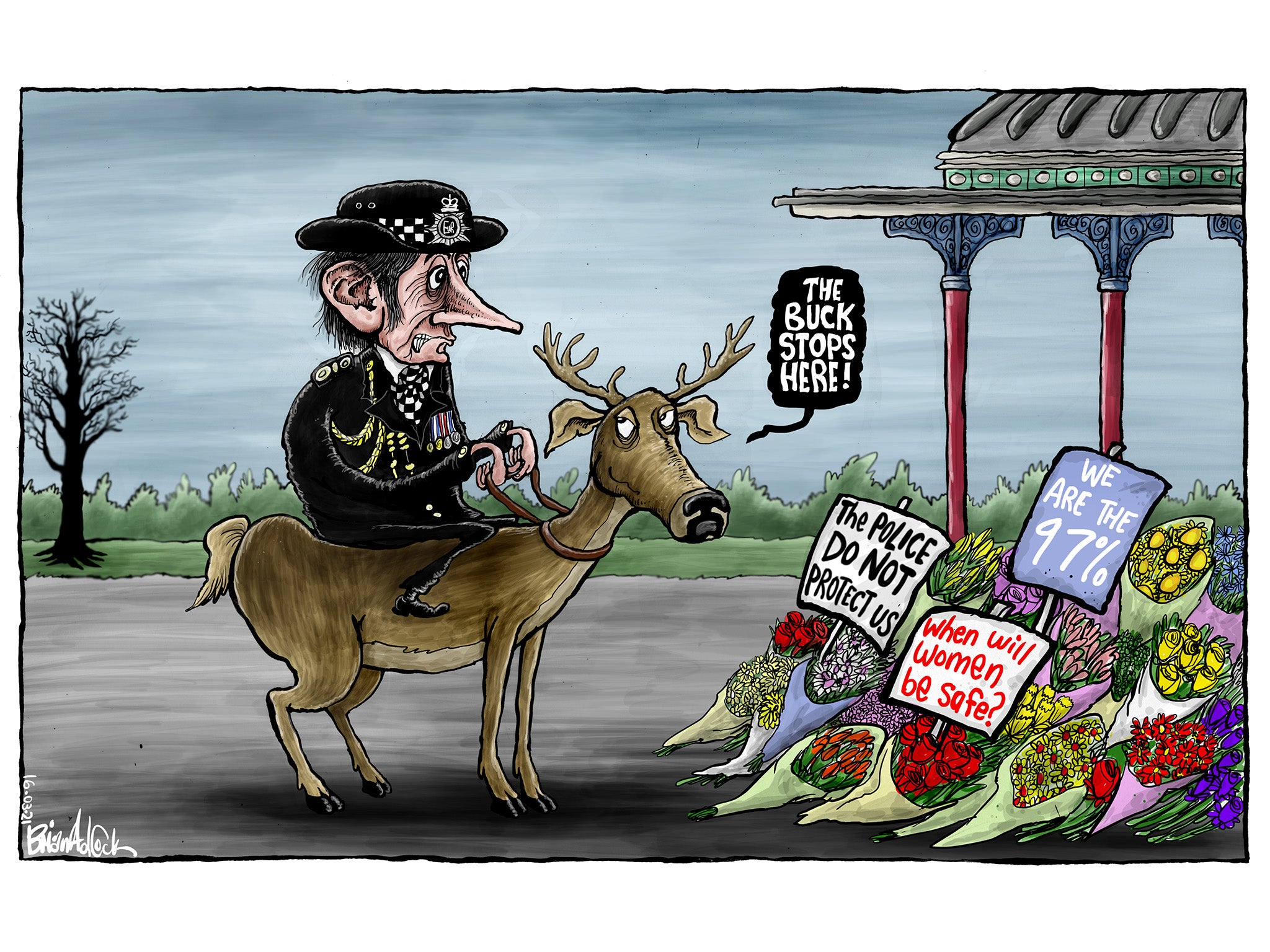

From what can be judged by the weekend’s television pictures and news reports, some of the police may have acted with undue force against unarmed, mostly female protesters, posing little physical threat to any officer; but that is now the subject of internal inquiries and a report from HM Inspectorate of Constabulary.

For the moment, calls for the resignation of the commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Cressida Dick, are premature – and look to be an overreaction. The Black Lives Matter protests, Extinction Rebellion’s deliberate disruption and the various counter protests prove how difficult maintaining public order can be even at the best of times. The pandemic made matters even more challenging.

Human rights are inviolable – and if they are to be constrained in an emergency, then more care needs to be taken to explain and gain consent for such changes. The government and parliament failed to do so during the panicky conditions of the Covid crisis, and it has left us with the current mess.

Yet even without Covid, the point about policing by consent along lines that command very wide public respect and clear legal requirements still stands. It is not obvious that the new legislation satisfied those criteria, and the chances are that confusion will persist and multiply in the years ahead.

There is far too much stress placed on what a “reasonable” person would regard as “reasonable” behaviour. A climate protester will regard it as perfectly reasonable to block major arterial roads because of the “climate emergency”; those going to work, waiting for an ambulance or on the way to pick their kids up from school would beg to differ. What is a “reasonable” amount of noise by a “single-person protest”? What is the point of protest if it goes unnoticed? Is it right to lock someone away for a decade for assaulting an inanimate object?

The new bill is bad law, and the best that can be said for it is that it will be disregarded, just as laws imposing a poll tax were 30 years ago.

The British cherish their freedoms, but, as our Tory prime minister never quite gets round to acknowledging, also have a tradition of rioting and disorderly disruptive protest to fight for things that are now celebrated by conservatives. “Reasonable” people were horrified when, not much more than a century ago, the suffragettes smashed windows, attacked policemen (for there were only policemen), and went on hunger strike.

Now, we have the comparative luxury of discussing whether a female police commissioner should be sacked by a female home secretary because of the way the police tried to uphold the law. No legislation passed in the Edwardian era to play cat and mouse with the suffragettes could stop women from winning their rights through noisy, chaotic protest. Nor will such a law prevail now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments