Vladimir Putin has kept all his options open in Ukraine – and divided the west with ease

Editorial: The price of peace, if such it is, has been to build up President Putin’s reputation as a global player to be reckoned with, and to leave Nato visibly demoralised and weakened

There may still be a long and bloody war in Ukraine, and one that no side can truly win. According to American intelligence released a few days ago, and with a curious precision, the war is imminent.

Such is the often inevitable consequence of vast troop build-ups and bellicose rhetoric, as well as years of distrust, rivalry and expansionism. The very mobilisation of troops on both sides can create its own momentum to war that overwhelms diplomatic initiatives and political manoeuvrings – “war by railway timetable”, as it was once styled.

The Russia-Ukraine war cannot be declared over. Yet, according to western sources, there seems to be some possible disengagement of Russian forces taking place around Ukraine, a little hope in the air. It is at least better than the visible arrival of yet more armoured divisions.

There is talk in the west about a window of diplomatic opportunity opening up. On the other hand, Russia is still constructing field hospitals, and its armies, freshly exercised, can be restored as quickly as they were deployed in the first place. Russian officials are mostly still talking tough. The most hopeful sign is that the talks between leaders are still taking place, including with Ukraine.

The chancellor of Germany, Olaf Scholz, is the latest to be filmed looking bemused at the end of President Putin’s new, globally celebrated, oval table. If there is to be a peaceful, diplomatic solution, the outlines of such a deal are already becoming clear.

Perhaps if Nato scales back its own strictly defensive force build-up in Poland, Estonia and elsewhere in the broad region in a voluntary, reciprocal, gesture, it might yet prompt further demobilisation by Russia. At the very least a peace “deal”, somehow grafted onto the now redundant Minsk accords, will require Ukraine to abandon or “suspend” its stated aim of joining Nato and the EU.

At the moment, a little unusually, the dearest hopes of the government of Ukraine and many of its people are enshrined in the country’s constitution. It is a token of how much Ukraine sees itself as a modern, democratic, European nation; no different to, say, Poland or Denmark.

Those devoutly held ambitions have long alarmed President Putin, who has said that he doesn’t regard Ukraine as a truly legitimate state, and sees its people as Russian in all but name.

It is ethnic nationalism in its purest and most arrogant and dangerous form. Hence the standoff and the annexation of Crimea and the occupation of Ukraine’s eastern provinces. The irony, of course, is that Nato as a “family” is unwilling to accept Ukraine as a new addition; a problem child, already semi-occupied by Russia.

So if Russia doesn’t want Ukraine to join Nato, and Nato doesn’t want Ukraine to join Nato, the only thing that stands in the way of shelving this particular point of largely theoretical conflict is the dogged determination of the Ukrainians themselves.

If they wish to retain the clause in the constitution, then it is up to them as a sovereign state; if they want to play their part in defusing tensions, amending it would go a long way. There is, however, no guarantee that Mr Putin won’t ask for more. He might press for international recognition of Crimea as part of Russia, and try to make the occupied eastern regions as autonomous from Kiev as possible.

Of course, the loss of Crimea and half of Ukraine’s territory to bogus Russian puppet “people’s republics” ought to give Russia rather more cause for reassurance about this security and nationalistic satisfaction. But Mr Putin has a large appetite.

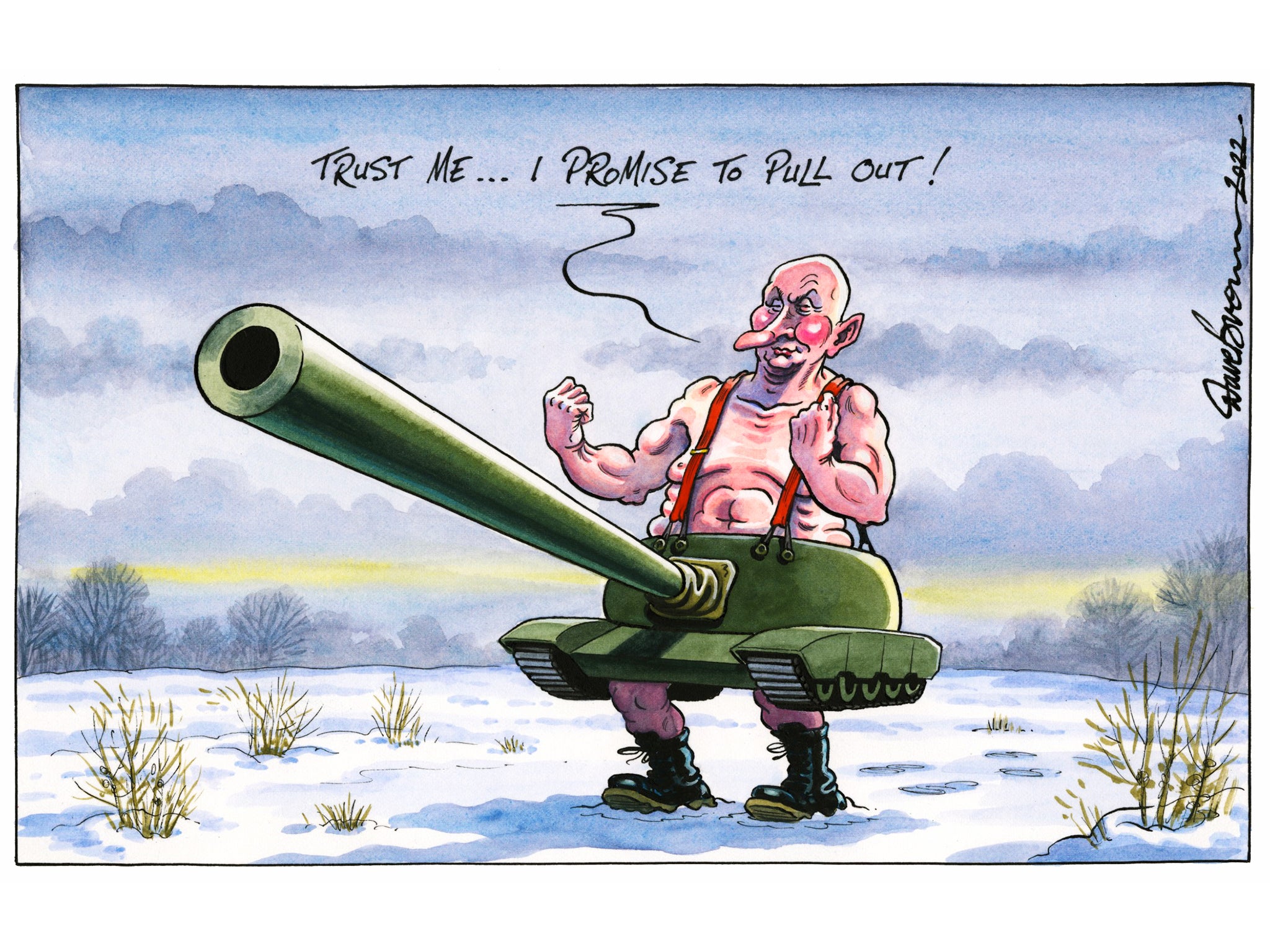

Without doing much more than making some threatening speeches, sitting western leaders at an oversized table and organising some military manoeuvres around Ukraine, there seems every chance that President Putin has proved a few points and will gain some valuable concessions – and has done so without firing a single shot.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

He has kept his options open, and divided the west with ease. The price of peace, if such it is, has been to build up President Putin’s reputation as a global player to be reckoned with, and to leave Nato visibly demoralised and weakened. Mr Putin can order his troops home having secured significant concessions from the west. His people will be impressed. He has played the game of appeasement. He’ll be back for more.

Taking a step back, it may appear an absurd situation. Russia is an industrially inefficient power with the GDP of Italy. It has natural resources, a talent for spying and space exploration, and a substantial military and nuclear arsenal; but lacks leading Russian software giants, AI pioneers or pharmaceutical innovators. President Putin knows his forces would likely be crushed by the west. The US remains a superpower, and the EU remains an economic superpower. The west has friends and allies around the world.

Still, even with Beijing partly covering his back, President Putin is leveraging the advantages he has to astonishing effect. For the west and Ukraine, the prospect of peace has a bitter aftertaste.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments