In his first speech of the new year, the prime minister rattled on enthusiastically about the power of innovation. As a country, we need “to put innovation at the heart of everything we do”, he said. No argument with that, but there was precious little that was especially new in these remarks.

The crusade against antisocial behaviour recalls similar rhetoric from Tony Blair and David Blunkett two decades ago. The lines of family values recall the ill-fated words of John Major. Gordon Brown would be impressed by the idea of rewards for hard work. The rubbery targets for the economy and public finances could have been dreamed up by George Osborne and David Cameron. Cheekily, Rishi Sunak even mentioned levelling up, while taking a few sneaky sideswipes at Boris Johnson’s failure to deliver much more than boosterish slogans in office.

Equally familiar is the politician’s old trick of declaring “unambiguous” new aims which are essentially just as ambiguous as they ever have been. Inflation will be “halved” this year, but from where and in what measure? Growth will return by the end of the year, but how meagre will it be? Debt will be falling, but after the next election. And the small boats “will be stopped”, but when, and would one stray dinghy count?

The five Sunak promises even recalled the New Labour “pledge card” gimmick of 2001. Then as now, the bar for success is set low.

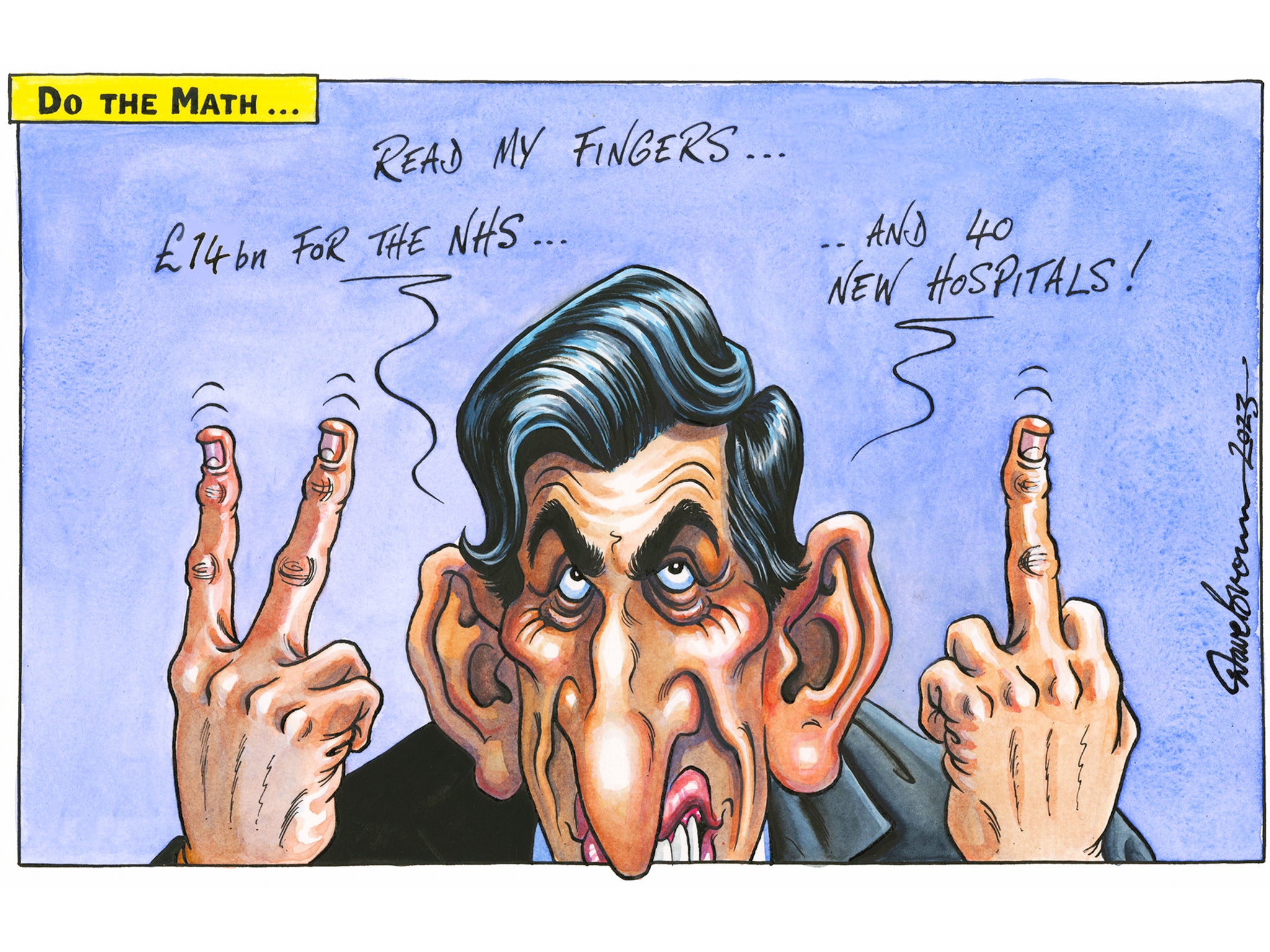

Nor did the prime minister have much to new to offer on the NHS crisis or the strikes; a major disappointment. The only innovative policy in the speech was the drive to improve mathematical attainment. Well, numeracy is a wonderful thing, and so is a prime minister interested in education. Had his predecessor and her chancellor paid more attention to arithmetic, the nation’s public finances might not be in the dire state they stand today. Whatever else, Mr Sunak cannot be accused of not being able to add up. He no doubt has spreadsheets that prove otherwise.

For the good of all, then, mathematics is to be taught in some form until the age of 18, though in what form and to what level isn’t yet known. A-level maths won’t be compulsory, but that’s about all Mr Sunak feels able to reveal. Will there be more statistics or calculus? More trigonometry? Will they bring back the slide rule?

In any case, it will be a tough job for teachers to entice the “numerophobic” for their extra tuition. Perhaps the best approach would be to educate pupils about practical matters, so they might better understand compound interest, mortgages, pound cost averaging, probability and risk assessments in areas such as investment or vaccines, and how an electric car works. Applied maths might be the best route to a better-informed society.

Even so, it’s not immediately apparent where the extra funding will be found. The £2bn boost to the education budget may already have been earmarked elsewhere, and the prime minister wouldn’t want to be accused of double counting. More to the point, there seems no plan to increase the supply of maths teachers to fulfil the prime minister’s ambition to nerdify the nation’s youth.

Mr Sunak knows the year ahead will be tough, economically and politically. He faces a severe electoral test at the local elections in May, and Mr Johnson, as ever, is on manoeuvres. The trends in the opinion polls need no great skill to interpret. His party is exhausted and looks fresh out of ideas. Mr Sunak’s speech didn’t recess that deficit, and his technocratic tone and messages lacked the kind of emotional connection that the best leaders make with the public.

The mathematical Mr Sunak needs to sound less like an earnest schoolboy showing off his homework, and more like a man who can get Britain working again.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments