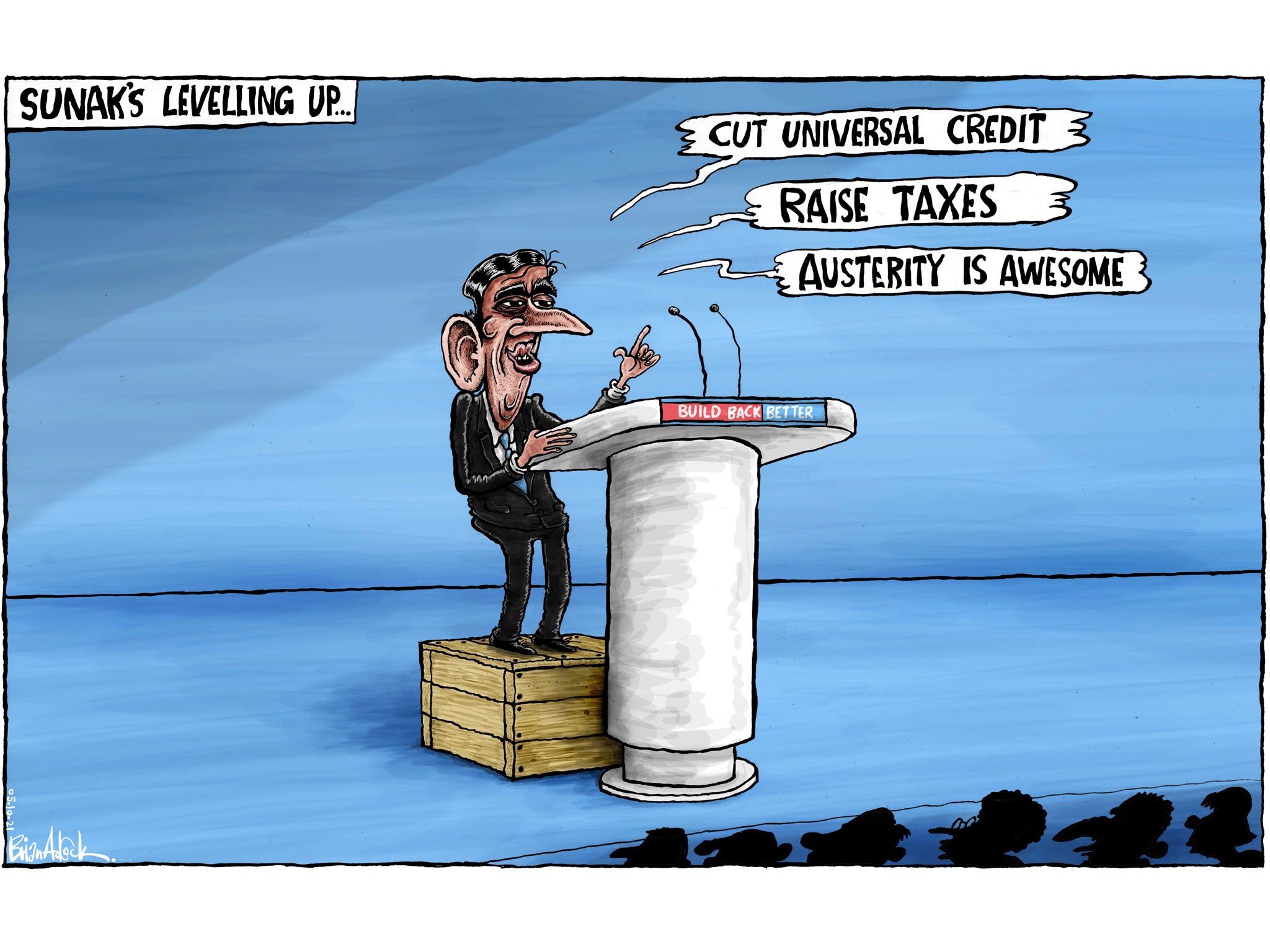

Rishi Sunak may not have used the word ‘austerity’, but it will certainly feel like it

Editorial: Back in the here and now, families face a severe squeeze on living standards. Even those in shortage occupations will find their inflated pay won’t go as far as they might imagine

As the country looks forward to a Christmas without turkey, toys, or even the traditional trees, there was at least no shortage of ambition from the chancellor of the exchequer.

Most of it was centred on his own political career, of course, and few at the Conservative conference would have missed the double meaning of his declaration that “the future is here”. The future is indeed Rishi Sunak-shaped (at least in the mind of Rishi Sunak).

Still, he also offered some afterthoughts about the future of the country, and they too were bold: “I believe we’re going to make the United Kingdom the most exciting place on the planet.”

At the moment, however, the excitement seems to be confined to finding a petrol station that’s open, or discovering a gas supply business that is still trading. The end of the furlough scheme, the cuts to universal credit, and national insurance increases next year – as well as the continuing disruptions to the supply chain – mean that the next few months won’t feel like the UK is reaping any great benefits from Brexit.

Indeed, as the effects of Brexit work their way through the economy, exacerbating the after-effects of Covid, many will wonder whether Brexit really has lived up to expectations.

Mr Sunak, though, is unrepentant about backing Brexit. He is unusual among rational people interested in economics in that he voted Leave in 2016, and he still believes in it, despite the fact that it is now making his own job much more difficult to do.

The “future” Mr Sunak talks about is one in which he predicted that “the ability, flexibility, and freedom provided by Brexit would be more valuable ... than just proximity to a market”. It will, in other words, come good, but it will take a good deal of time.

His cabinet colleague Jacob Rees-Mogg was once kind enough to put an estimate on that of about half a century. Mr Sunak is not so obliging as to offer a timeframe for the rebirth of the British economy. It looks fairly sickly at the moment, in any case.

It may have the fastest growth rate in the G7, but then again, it has one of the worst Covid death rates, and its economy has slumped quite badly. As far as can be judged, the economy remains smaller than it was before Covid, and growth will be constrained by the loss of markets that Brexit has engendered.

Meanwhile, back in the here and now, families face a severe squeeze on living standards. Even those in shortage occupations will find their inflated pay won’t go as far as they might imagine given the ramping up of inflation: one person’s pay rise is another person’s price rise, as the old adage goes.

Mr Sunak is also finding it difficult to make ends meet, as he told his audience. That’s no great surprise to anyone, but he seems to be in too much of a hurry to do something about what he calls the “immoral” level of the national debt.

He’s told Boris Johnson that he’s “cut up his credit card”, and that if the prime minister wants to launch any new royal yachts then there will be tax rises – not cuts – before the next election. That is good news, but there is also talk of yet more constraints being applied to public spending, even as the British economy struggles to recover, uniquely, from Brexit as well as Covid.

The funds going towards educational catch-up, for instance, are paltry; and there will be yet more senseless cuts in local council spending, provoking a “stealth” council tax rise.

The trick is that the public will blame town halls rather than Whitehall, and it may work politically, but it will leave councils unable to provide essential services. Stealthy or otherwise, tax hikes and spending cuts now seem inevitable. When the national debt was pushed skywards by past great national crises – including two world wars – it was managed downwards over a period of decades.

Precisely what Mr Sunak has in mind won’t be known for sure until his Budget and spending review towards the end of October, but the signals are ominous. In his speech to the activists he could not bring himself to utter the word “austerity”, though he did praise his predecessors who had implemented that policy.

Mr Johnson dislikes the word, and only last month Mr Sunak pledged: “What we’re going to see is absolutely no return to austerity.”

Whatever the chancellor chooses to call it, though, to many hard-pressed families and dedicated professionals working in schools, hospitals, the armed forces, local authorities and elsewhere, it will certainly feel like austerity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments