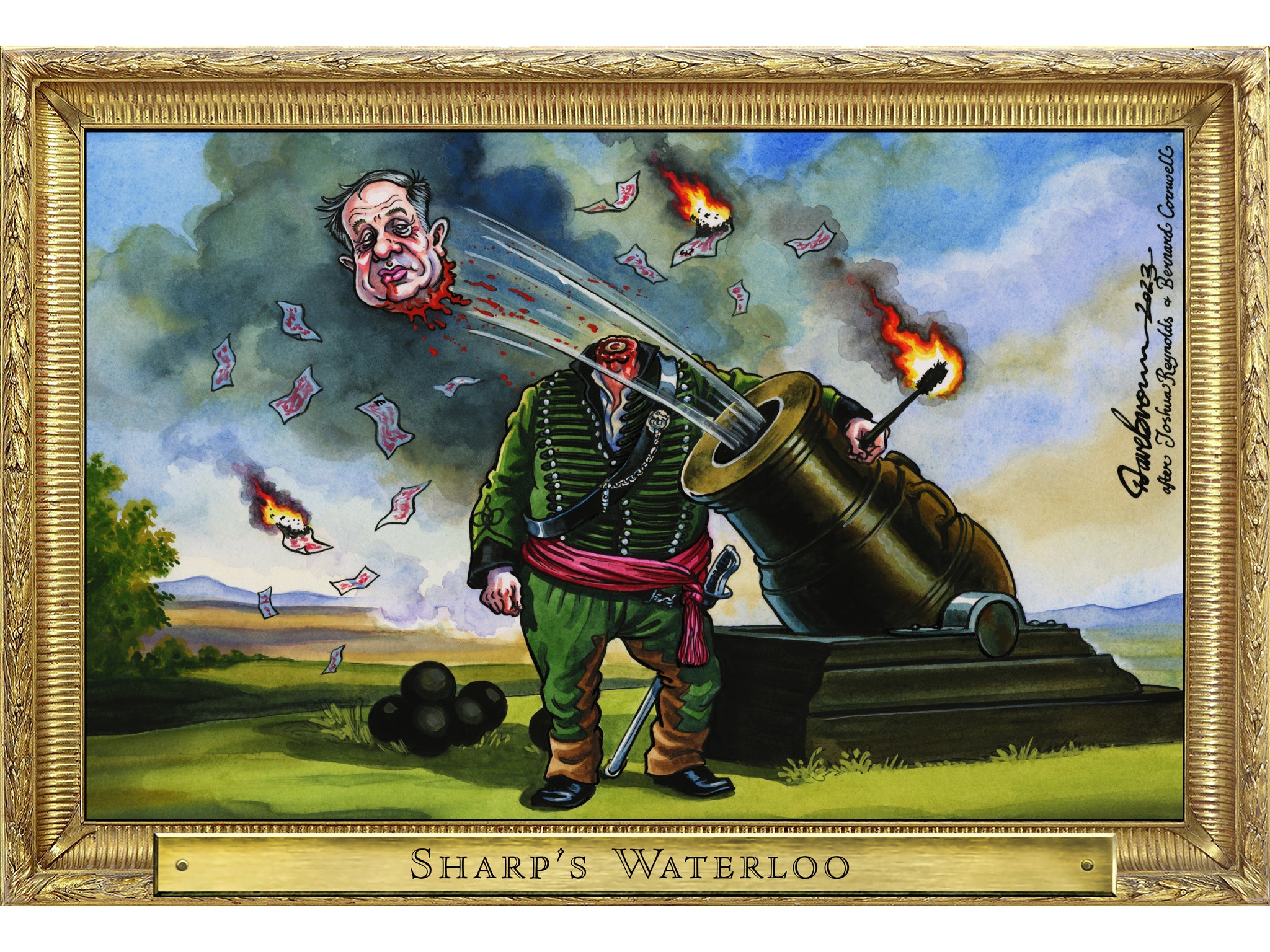

This is about doing things properly,” said Rishi Sunak when he was asked why he hadn’t sacked Richard Sharp some months ago over Mr Sharp’s limited role in facilitating the £800,000 credit line made available to Boris Johnson in 2021 when Mr Johnson was prime minister.

Fundamentally, Mr Sharp would still be in post, and doing a perfectly good job, if he hadn’t got tangled up – however tangentially – in Mr Johnson’s personal financial problems.

If Mr Sharp was intending to present himself at any point as a plausible nominee for the role of chair of the BBC, then he and Mr Johnson should have avoided any activity at all that might give rise to the perception of a conflict of interest. That is the genesis of this affair, and that is why it is what might be termed a “legacy scandal” – another messy problem left over from the Johnson administration for Mr Sunak to clean up.

Mr Sunak should have got the mop and bucket out much sooner, however. For honourable and understandable reasons, Mr Sunak wanted due process to be applied, and a report on the matter was commissioned from the Office of the Commissioner for Public Appointments.

Yet this was essentially otiose. The facts were not in doubt; not least that Mr Sharp had appeared before the House of Commons select committee on culture, media and sport and had made no attempt to declare any actual, or perceived, conflict of interest.

Nor did he declare such a conflict to anyone else, except the cabinet secretary, Simon Case. It seems Mr Case chose not to take the matter further, and not to advise Mr Sharp that his application was fraught with problems and therefore unlikely to be sustainable. The truth and the context, all concerned ought to have known, would out, sooner or later. And then there’d be trouble.

All of this was well known and not in dispute when, in late January, the media broke the story. It was at that point that Mr Sunak should have acted and encouraged Mr Sharp to leave with some dignity. In addition, Mr Sharp ought to have recognised that, even if he managed to survive the investigations by the BBC, the Commons select committee, and the Office of the Commissioner for Public Appointments, his authority would be irretrievably compromised.

He has now decided to do the right thing, but he should have gone sooner. If Mr Sharp wasn’t prepared to step down in January, then Mr Sunak should have pushed him.

It is all part of a pattern of behaviour by Mr Sunak, wherein he seems reluctant to wield the power of his office. He is not, in William Gladstone’s famous phrase, a “good butcher”. Mr Sunak seems to behave too much like a nervous HR manager looking over his shoulder at an unfair dismissal claim, and not enough like a leader who understands that politics is a rough old game and one in which national and party interest should trump friendships, sentimentality, or, indeed, due process.

It was not something that troubled, for example, Tony Blair, who discarded ministers, including some of his closest allies, as casually as he might a sweet wrapper if they became inconvenient. While in most walks of life Mr Sunak’s quasi-judicial approach to duty of care would be an admirable strength, in a prime minister it is a distinct flaw.

He might also want to reflect on why so many of his other appointments, such as those of Gavin Williamson and Suella Braverman – both unforced errors – have proved so problematic.

All of that said, Mr Sunak has been charged with fixing many of the things Mr Johnson left broken. Only this week, we saw the announcement that Chris Pincher would be standing down at the next election – Mr Johnson’s attempt to save Mr Pincher having been the immediate cause of the downfall of the last prime minister but one.

Soon, Mr Sunak will have to deal with the ultimate Johnson legacy scandal, when the Commons committee of privileges reports on whether Mr Johnson lied to parliament.

As Mr Sunak always maintains, it is a matter for the Commons as to what they do to Mr Johnson if he is found to have acted in contempt of parliament. Yet the prime minister should not be too fastidious if his colleagues decide that the preservation of standards in public life, as well as the fortunes of the Tory party, would be better served by Mr Johnson’s removal from his role as a member of parliament.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments