Protests in China have a pre-revolutionary feel to them

Editorial: Xinjiang happens to be one of the many areas where the usual modest-sized (but noisy) protests about routine concerns have evolved into larger, less orderly and rather more politically charged protests

As with the disturbances in Iran (and, to a lesser degree, Russia) the wave of protests breaking out in China have something of a pre-revolutionary feel to them.

Or, perhaps, a pre-pre-revolutionary feel, given that the Communist Party of China has maintained a firm and wary grip on the people of China since 1949. It has ruled through self-inflicted famines, breakneck industrialisation, brutal suppression in Tiananmen Square, oppression in Tibet and Hong Kong – and, lately, allegations of genocide of the Uighur people in the province of Xinjiang.

Xinjiang happens to be one of the many areas where the usual modest-sized (but noisy) protests about routine concerns have evolved into larger, less orderly and rather more politically charged protests. In Xinjiang, residents in a block of flats burned to death because the doors had been locked as a Covid measure, and they couldn’t escape.

The anger was real and justified. The demonstrations have evolved from random small groups objecting to zero-Covid and compulsory lockdowns to larger crowds in the major cities – such as Shanghai –calling for President Xi to stand down, and the communists to give up power.

The Chinese Politburo isn’t known for its sensitivity to public opinion, and there are signs that the authorities are getting tough. Yet even the hardest of hardliners in Beijing must have some cause for reflection about how rapidly the unrest is spreading.

The Chinese people have had enough of the lockdowns because, after four years, there is no reason to believe that the zero-Covid policy will succeed in a world where the coronavirus is endemic. Even the hermit kingdom of North Korea has been unable to prevent cases of Covid, and China – well integrated into the world economy – could not remain Covid-free for long, in the unlikely event that zero-Covid was ever to be achieved.

The World Cup in sunny Qatar, bizarrely, may have prompted Chinese viewers to wonder how it can be that thousands of people from all over the world can gather in stadiums without Covid chaos breaking out. The clumsy censorship of the fans, blurring out their maskless faces, can only have sown more suspicion about how the rest of the world was managing to suppress the virus without locking down entire metropolises.

The Chinese people seem to be asking awkward questions of their rulers, and increasingly see that widespread vaccination allied to voluntary testing and self-isolation, as in the West, is a more effective and humane way to deal with Covid.

If it were just Covid policy that the CCP had got wrong it would be bad enough; but the people of China have an even longer list of grievances – most of which represent government and CCP failures. Corruption is no less endemic than Covid, and it has led to shoddy building and tragedies when schools or apartment blocks collapse.

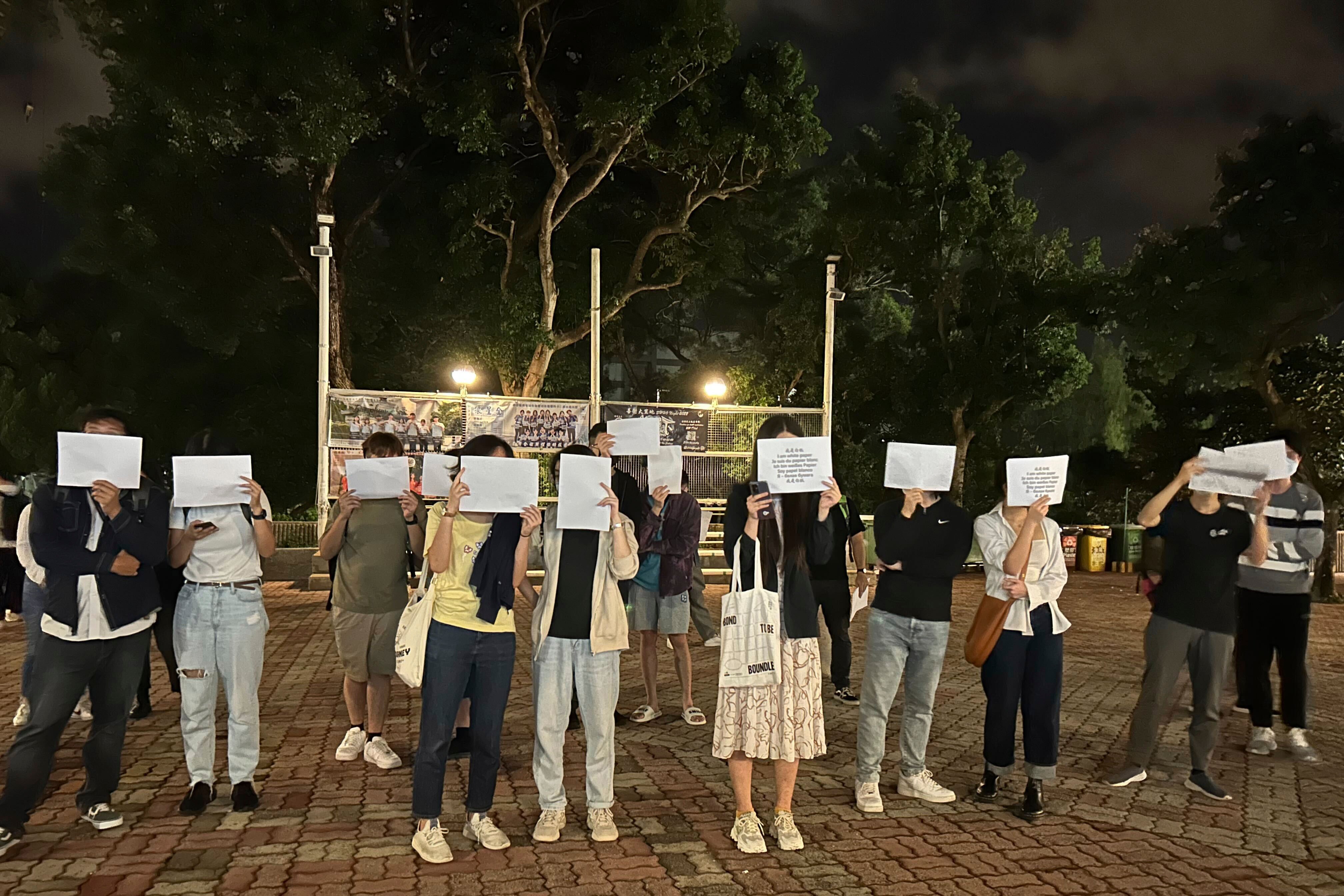

Working conditions in the factories are notoriously poor. Students and intellectuals are frustrated by censorship. Everyone would like some freedom of speech, and they can try and exercise it on a street holding up a poignantly blank sheet of paper.

Because the West now views China with such mistrust, it is shunning its technology and “reshoring” supply sources to places such as India and Vietnam, as well as back to Europe and North America. That will inevitably hit the Chinese economy, which needs to generate 10 to 20 million new jobs a year just to keep up with its college leavers. More economic troubles ahead, then.

Moves to deglobalise, such as the latest US ban on Huawei and others, will hit China hard.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

China, like Iran and Russia, is a country which is in a more or less permanent state of war with its own people. Like those other authoritarian regimes, ethnic minority groups find themselves persecuted even more relentlessly, but the abusive relationship between leaders and people is near universal.

And across the three, along with others on the axis of absolutism, such as North Korea, the regimes are durable. But they were born of revolution, and they are vulnerable to counter-revolution – and at times and circumstances that cannot be easily predicted.

The fall of Xi and the Chinese Communist Party is not at hand, and there’s every chance that there will be a quiet change of policy away from lockdowns and towards vaccination. Provincial officials and businesspeople will be blamed for “mistakes”. Things may calm down.

But the people will remain unhappy, and they know who is responsible for decision-making in their highly-centralised nation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks