The Met’s Partygate investigation must be swift and decisive to restore public faith

Editorial: The public has a right to know whether its rulers obey the laws they impose on others – and whether the taxpayer-funded police force is upholding the law without fear or favour

One of the more obvious bits of collateral damage from Partygate has been respect for the rule of law and, subsequently, the reputation of the Metropolitan Police Service for responding to crimes without fear or favour.

As more and more serious allegations about Covid rule-breaking emerged, mostly unchallenged in their substance, the Met stuck to its line that it did not unusually investigate such crimes after about a year has passed. With such a politically charged set of allegations growing almost by the day, the Met left itself open to much ridicule.

The Met, its commissioner, Cressida Dick, and its senior officers perhaps took the view, repeated by Commissioner Dick on Monday, that it wasn’t the best use of scarce police resources, and that they’d be better off pursuing terrorists and violent criminals rather than spads with hangovers. Now it seems something has changed her mind, and the Met will, after all, be going after those who broke the very laws they made during lockdown. It is about time.

Perhaps the Met has decided to respond to the mood of Londoners and the crumbling respect its police force commands. The levels of public confidence in London’s police – of national concern given the places they are guarding – is collapsing to dangerous levels, stressed by the Covid regulations and the impression of lawlessness in Downing Street, ironically the most heavily policed neighbourhood in the country.

When there are police officers stationed in and around Downing Street who must be able to hear unlawful disco parties in the basement and ignore them, then the law-abiding public, and their representatives in the London Assembly, have a right to ask what’s going on.

Policing by consent requires that the public regards its police force as trustworthy, on its side, and impartial. Yet a series of recent appalling scandals, such as the kidnap, rape and murder of Sarah Everard, has badly damaged that faith. The idea that the Met would turn a blind eye to the goings-on in Downing Street while slapping fines on hapless partygoers elsewhere has been inflicting still more grievous damage.

If, in future, police officers anywhere in the UK have to enforce harsh rules and restrictions on public freedoms, then they may find it much more difficult. People can simply turn around and say: “If Downing Street doesn’t obey the rules, why should anyone else?” In the event of future emergencies, we could find the authority of the police and the courts weakened, and public health at greater risk.

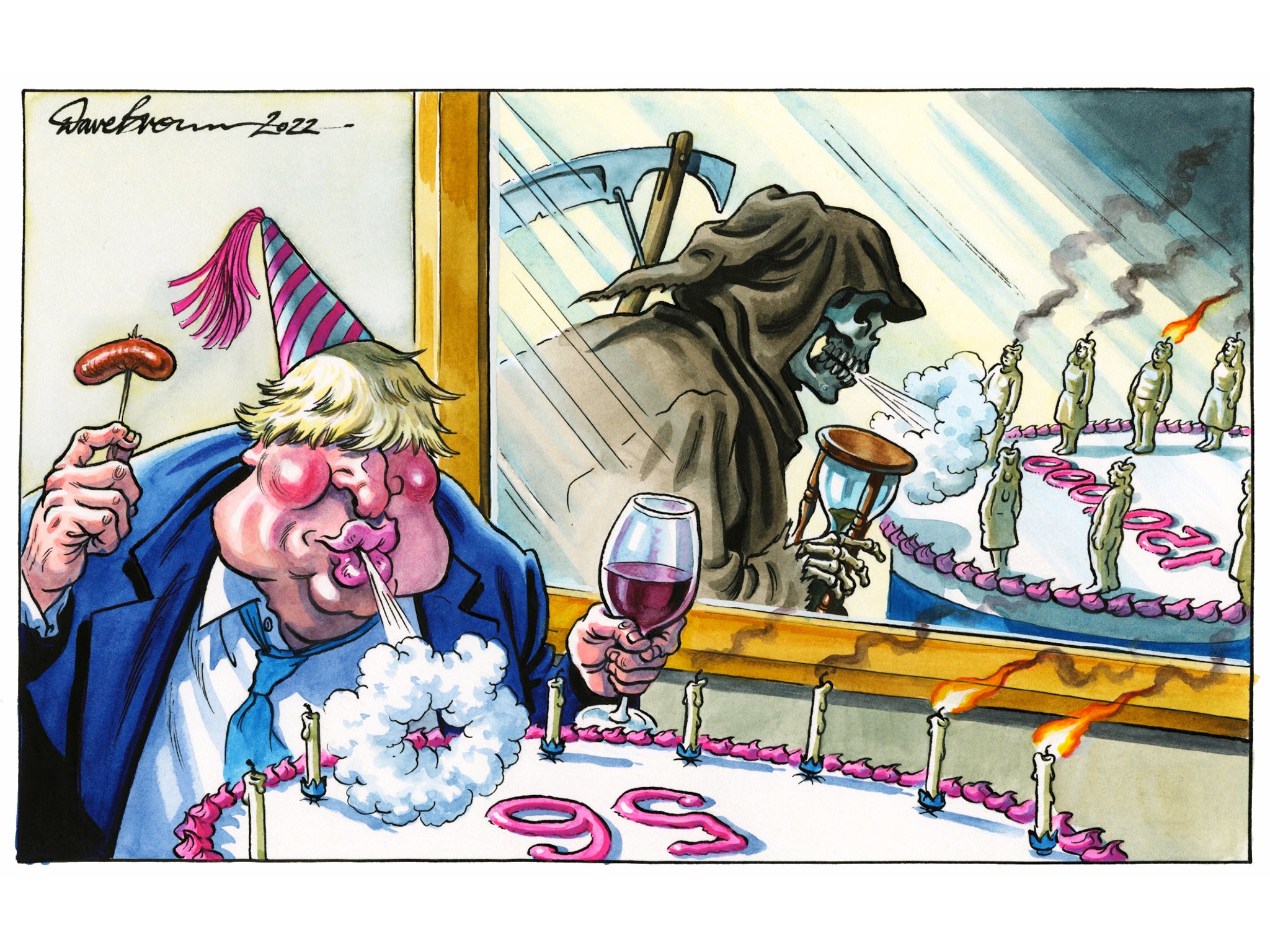

So Commissioner Dick has had to act, at long last. Sue Gray, a senior civil servant with a keen sense of procedure, has been liaising with the Met, and evidence has been supplied. Not investigating such potential lapses as Ms Gray has identified would, in Dick’s words, “significantly undermine the legitimacy of the law”. She says that only “the most serious and flagrant type of breach” justified retrospective attention. The concatenation of unlawful “gatherings” would seem to amply satisfy that criteria. There’s plenty of evidence, too.

In a way, Ms Dick and Ms Gray are playing catch-up with public opinion. Thanks to a much-maligned free media, much that was scandalously covered up about parties and illegality in lockdown has been forced into the public domain. Were it not for the reporters and those willing to blow the whistle on the apparent culture of hypocritical law-breaking then all of this would have remained secret indefinitely.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

Now the revelations are out there and the debate is raging, just as it should be. The public has already made its mind up about the alleged lawbreakers and the police who have taken until now to do anything about it. It is not a conspiracy and cover-up, but too many will suspect that it is.

Even if Ms Gray and Ms Dick exonerate all concerned, the British people will not accept that. The public has a right to know whether their rulers obey the laws they impose on others – and whether the taxpayer-funded police force is upholding the law without fear or favour, with no one above it.

Had the public, in the spring and summer of 2020, known about the garden parties, the birthday party, the Friday night wine, or the late-night sessions on the eve of Prince Philip’s funeral, there would have been outrage, but most likely much less compliance with the guidance. The anger directed at Dominic Cummings, Matt Hancock and others caught breaking the law shows that very well. Non-compliance wouldn’t have been justified, but it would have increased and it would have cost lives in that pre-vaccine world.

The arguments now are not about whether cake was taken at some little celebration, but about a whole depraved culture of law-breaking and betrayal of trust at the heart of government. If it has infected the civil service and the police force, then it must be cleansed.

Commissioner Dick and Ms Gray will need to do whatever they have to in order to restore public confidence in the institutions they serve. Transparency and disclosure, punishment and due process will all be key. Ms Gray’s report needs to be published in full, and the Met must inform the public about the progress of its work. It should not take long. Justice will be done and be seen to be done, with fixed penalty notices and more serious penalties for those who organised the parties, just like for other, less powerful citizens. Nothing less will restore faith in the police.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments