As a reputation management exercise, the Coutts review of Nigel Farage’s account with the bank went about as badly as it possibly could.

The minutes of the bank’s wealth reputational risk committee, which Mr Farage obtained by the simple legal expedient of a subject access request, reveal that executives were worried that having Mr Farage as a customer might reflect badly on the bank’s wish to be seen as “inclusive”.

So they concocted a case for closing his account, which mentioned the modesty of the amount of money in it, but which mainly rested on the perception of Mr Farage by much of liberal opinion as a xenophobe.

From this original misjudgement, further errors followed. Dame Alison Rose, the chief executive of Coutts’s parent, NatWest, in an unattributable conversation at a City dinner gave Simon Jack, the BBC’s business editor, to believe that the account had been closed because it did not meet the threshold required.

Not only did this disclose confidential details of Mr Farage’s account, but it was doubly misleading. Many of Coutts’s customers are allowed to keep accounts that fall below the threshold, especially if, as in Mr Farage’s case, the drop is expected to be temporary. But critically, as the minutes reveal, this was not the main reason for closing Mr Farage’s account.

When Dame Alison admitted on Tuesday that she was the source of the BBC’s misleading report, NatWest’s chair, Sir Howard Davies, and the other directors decided that the double blow to the banking group’s reputation had not been serious enough. Not only had it closed someone’s account because of their political views and its chief executive had caused an untrue version of events to be published, but its board now decided to stand by Dame Alison, declaring that it had “full confidence” in her.

By then, the public relations disaster had become so great that some members of the board realised the position they had taken on Tuesday morning was unsustainable. The prime minister and the chancellor had expressed their concern. They did so not because they represent the British people, who own 39 per cent of NatWest, but because ministers have rightly chosen to stay out of operational matters. And they did so in defence of the universal principle of free speech – that services should not be denied to anyone on account of their political beliefs.

A further board meeting was convened on Zoom for 11pm on Tuesday night to bow to the inevitable. Dame Alison would step down “by mutual consent”.

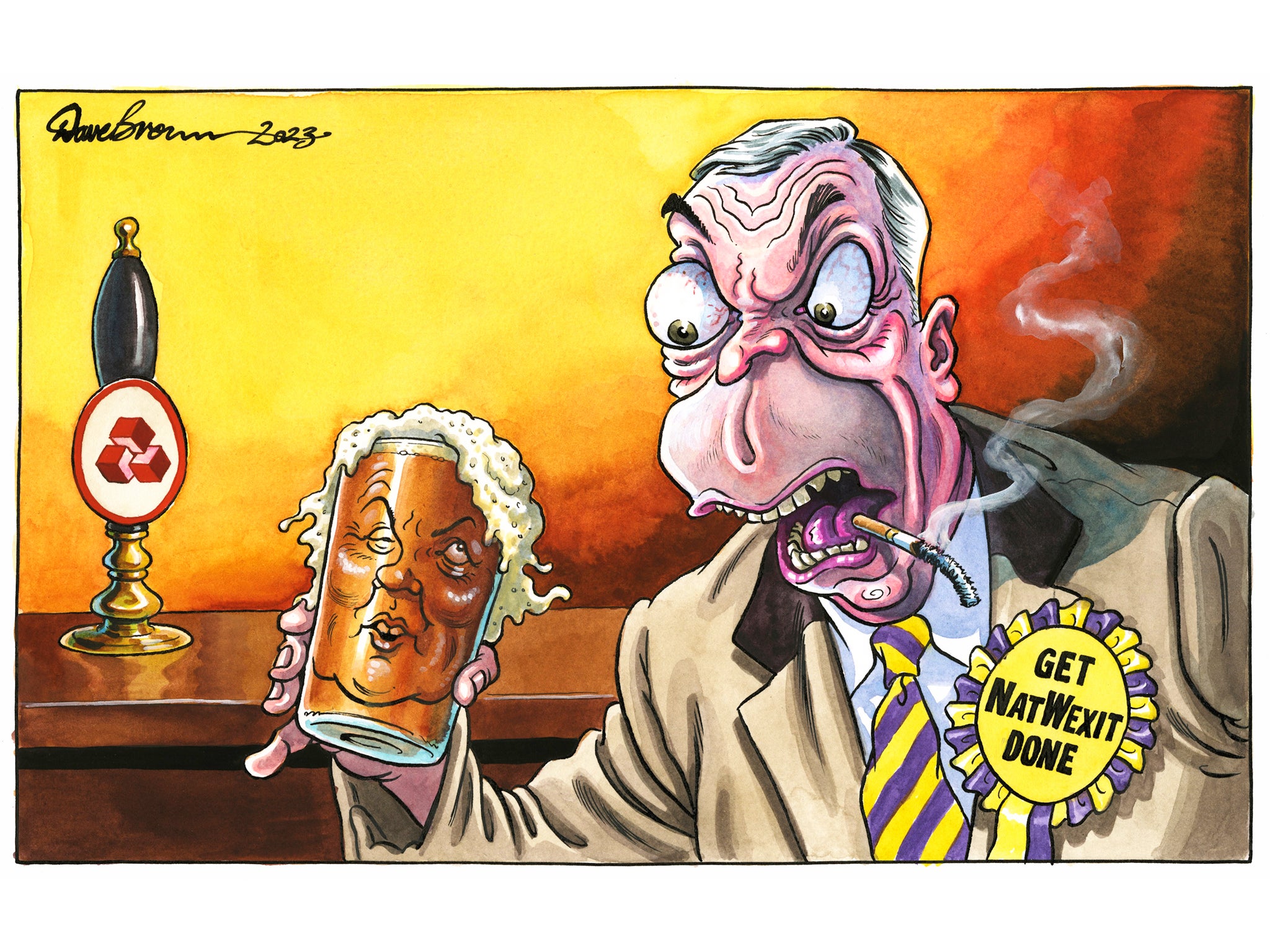

Thus ends the main drama of a salutary tale for our times. There will be aftershocks, as Mr Farage calls for the rest of the NatWest board to resign, and the opposition accuse ministers of being readier to defend the former leader of Ukip and the Brexit Party than the “ordinary” victims of other forms of corporate malpractice.

But it is almost universally accepted that Coutts was wrong to “de-bank” Mr Farage, adding a crime against the English language to its other offences to be taken into consideration. If Coutts had been a private members’ club, with a boutique banking service attached, it might have been able to argue that it would be entitled to choose who to accept or reject as a member.

But as a mere bank, especially an “inclusive” one, and especially one that is a subsidiary of the semi-nationalised NatWest, it could not deny a service to someone on grounds of their politics. Mr Farage is not a terrorist or a money launderer. The Independent disagrees with many of his opinions. Indeed, we disagree with him so much that he was, for a time, a regular Independent columnist. When we say we believe in freedom of expression, we mean it.

When Coutts reviewed Mr Farage’s account, one executive pointed out that its customer might go public about the snub, and that this might be a problem for the bank. To which someone should have said, “You think?” and shut down the exercise.

Let us hope that any British company tempted to take virtue signalling too far has learned the lesson of this case study in how to destroy a corporate reputation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments