Nato will barely survive its 70th year if it continues to neglect the mutual security of all its members

The organisation does many things well, and it must be preserved. However, there are lessons to be learnt when it comes to modern threats like terrorism, cyberwarfare and proxy wars fought far away

Given that Nato has kept the peace in Europe, if not the world, for seven decades, its 70th birthday party in Watford, appropriately enough, is turning out to be a rather low-key, down-hearted and underpowered affair. They’ve not even invited Elton John along.

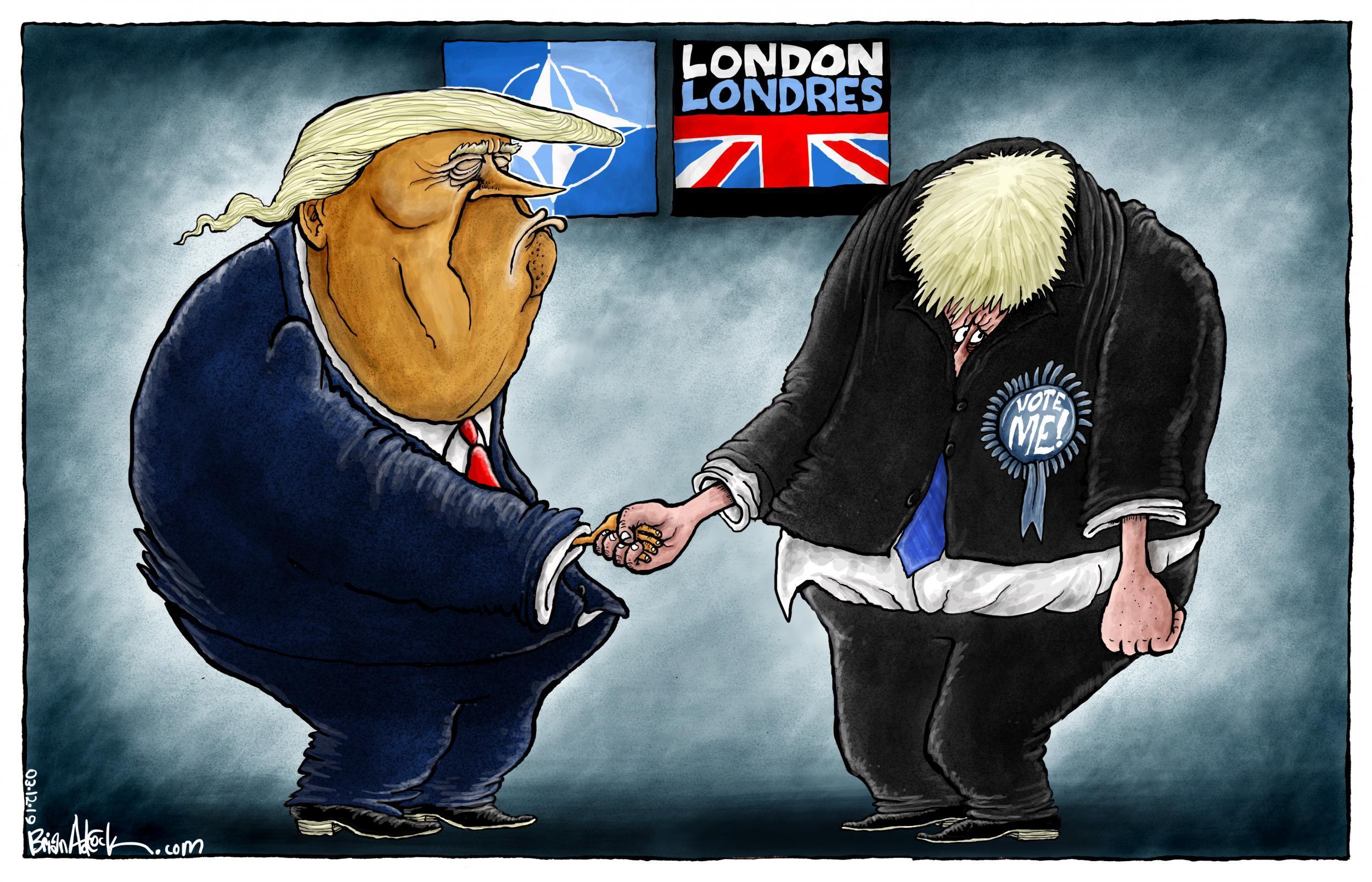

The birthday presents have certainly not been up to much, especially given the season. Not so much a “Joyeux Noel!” from Emmanuel Macron, instead comes a sneer that Nato is “brain dead”. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey would rather be at someone else’s party – Vladimir Putin’s – and can’t seem to make his mind up whose side he is on. Donald Trump is as grumpy as ever about paying the bills. Boris Johnson, the jolly host, wants to avoid any photo opportunities with his most powerful guest, the US president, because there’s an election on and Mr Trump is a toxic commodity for much of the UK’s electorate.

Other than that, all is harmony.

It would not matter, so much, if the criticism of Nato were of the type that is (supposed) to occur within families – constructive, fraternal, and with an aim of strengthening rather than dissolving the group. It does not feel that way. President Macron’s disobliging remarks are a thinly disguised attempt to create a French-led European replacement for Nato. The president, in true Gaullist tradition, has long held the view that the European Union’s problems, including its defence, can be solved by “more Europe” – but more of a Europe under French tutelage and guidance.

Mr Macron has maintained some of the traditional semi-detached attitude towards enmeshing French forces in Europe’s operational activities, especially the French nuclear deterrent. Also in true Gaullist fashion, he is advocating a softer, gentler approach to Russia, despite all the evidence of Vladimir Putin’s malign intentions towards France’s Nato allies.

President Trump is no doubt sincere in his resentment that few of Nato’s European partners live up to their obligations to spend 2 per cent of their national income on defence, which is mainly for the use of Nato. The Americans spend around half as much as this, as a proportion of their GDP. Critics of Mr Trump claim this is simplistic, because America has global defence commitments far beyond the North Atlantic zone. True, yet America’s efforts to restrain, for example, North Korea and guard against Chinese expansionist tendencies are also a benefit to the European branch of Nato (not to mention America’s defence allies in Asia and Australasia, some of whom are equally stingy about their defence budgets). It is unfair to expect the United States to always carry so much of the burden. The distrust and dislike of the current incumbent of the White House should not distract European leaders from fulfilling their solemn obligations.

President Erdogan, meanwhile, is spending his defence budget on buying a Russian air defence system, after US officials refused to supply him with theirs. They are also refusing to sell him modern American manufactured jets. He believes that Nato is cramping his freedom to deal with Kurdish separatists, who he regards as unalloyed terrorists. Nato believes, with more reason, that his invasion of Syria is at best unwise, and his dalliance with Russia, historically a regional rival since the days of the Ottomans and the Tsars, to be a gross strategic error.

The short answer to all of these varied criticisms and discontents is that Nato, for all its faults, is still the only game in town for the mutual security of all its members. Mr Macron, and those who sympathise with him, need to understand that the revocation of the US-Russia INF treaty opens the possibility that the Russians will be able to deploy medium-range nuclear warheads that could reach and obliterate Paris and every other European city.

Only the Americans have the nuclear capability and economic resources to counter such a threat; and Nato is the only structure whereby that deterrent could be exercised. President Erdogan might, before it is too late for Turkey, come to see that Mr Putin is merely playing him for his own purposes. President Trump will not last forever in the White House and Nato will probably outlast him. Either he, or his successor, should wonder whether a world in which much of Europe came under Russian influence is one where the American interest, and America itself, is best protected.

The only instance, in fact, that Nato invoked Article 5 for the first time in its history was after the 9/11 terrorist attacks against the United States: “The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all.” That deserves to be recalled at this time.

Nato does many things well, but is less agile when it comes to modern threats – terrorism, cyberwarfare, proxy wars fought far away. Nato’s well-equipped armies, professional command structures and nuclear arsenal have proved remarkably useless in deterring Russia from, variously, murdering people on the streets of Salisbury; a dirty little war in Georgia; preventing annexation of Crimea and eastern Ukraine; launching attacks on vital internet infrastructure; interfering in UK and US elections; and funding armed factions across the Middle East.

Nor, more understandably, has Nato been much use in curbing China’s projection of naval power in East Asia, and its advancements via the Belt and Road Initiative everywhere from Sri Lanka to Italy.

At 70, then, some of the family have become used to taking one another for granted, and all have made a habit of taking Nato for granted. It is, though, as the German chancellor Angela Merkel is clear-sighted enough to say, that “the preservation of Nato is in our fundamental interest, even more than in the Cold War”.

Germany has more reason than most to understand the realities and the dangers of great power rivalry. The British, by contrast, are simply too preoccupied with Brexit (and the security concerns that accompany that) to be of much use in bridge-building between America and Europe. Chancellor Merkel is right, though her enthusiasm for the organisation would carry more weight if her nation, one of the world’s largest economies, spent more on its defence than 1.2 per cent of GDP, and if Germany’s defence forces were less dysfunctional. Still, at least someone at the birthday party has brought a cake, even if it’s a cheap one.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks