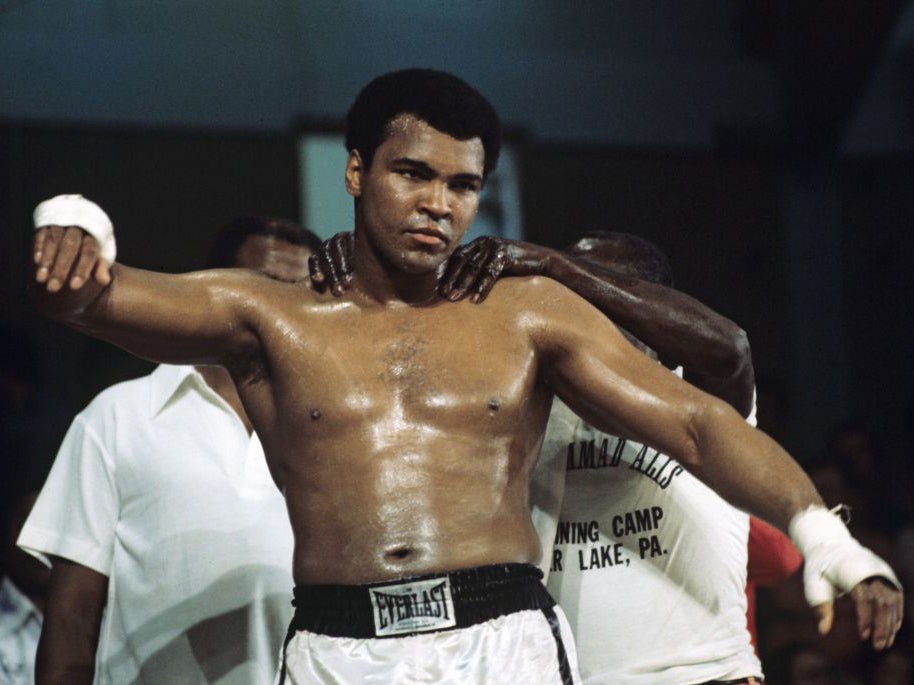

Muhammad Ali was the inspiration for a generation

Has any one man in our time inspired so many people to fulfil their potential?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When, at the turn of the millennium, the BBC awarded Muhammad Ali the prize of Sports Personality of the Century, his mind had by then been subjected to nearly two decades of Parkinson's disease, but had lost none of its mischief.

"I had a good time boxing..." he stammered, "... and I may come back." The truth is, he never went away. From the minute Cassius Clay, the fast-talking, irresistibly attractive son of Louisiana, was let loose upon the world, he was the most inspirational, galvanising and eloquent icon sport has produced.

Has any one man in our time inspired so many people to fulfil their potential? Several generations of children have tried to think like him, move like him, talk like him and look like him. His confidence and sheer charisma had a singular quality, but so powerful was its effect that countless would-be heroes have tried to ape his achievements. None did and none will.

Though he later transcended sport, it was first and foremost as a boxer that Ali captivated the planet. The man who floored Sonny Liston seemed, as all sporting legends do, to master the techniques of his profession while inventing skills others hadn’t yet dreamed of. In method and philosophy, Ali the boxer was that special thing: an original. He had the fastest feet and sharpest jab of any man to enter the ring, as well as a better understanding of the space around and available to him than any who came before or after. By the time he defeated George Foreman in the Rumble in the Jungle – perhaps the most hyped match in the history of sport, and one that lived up to that hype – he had given memorable linguistic shape to his approach: "Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee."

This exquisite formulation carried all the hallmarks of powerful English: a readily accessible metaphor; monosyllabic words; and moral force. It was the power of Ali’s language that allowed him to capture as many hearts as he did. Many champions, in sport and elsewhere, have bags of braggadocio; few could articulate it in the smooth, Southern drawl that became his hallmark.

When he launched himself upon British cameras ahead of his bout with Foreman, and declared his opponent "ugly", it was as much how he spoke as what he said that injected new drama into the occasion.

Yet it was the point at which Ali went from heavyweight fighter to, first, religious and black icon, and then conscience of a nation, that secured his impact on his history. There is always something unappealing about the zeal of the religious convert, and in his fawning attachment to cult leaders such as Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad, Ali succumbed to the immature conspiratorial thinking and victimhood mentality that occasionally tarnished the fight for equality in post-war America. As a champion of black emancipation – he revolted against "Cassius Clay" because, he said, that was his “slave name” – Ali ranks with Martin Luther King Jr and Bob Marley as one of those who, in the 20th century, did more than almost any others to force an end to shameful oppression. As a devotee of the Nation of Islam, he was less effective in redressing historic wrongs or curing modern ills than when he demanded equal rights for black people.

When he said he would not fight in Vietnam, he became a conquering hero to all those who felt, rightly, that America's misadventure in Asia was being driven by morally bankrupt foreign policy. The timing of his conversion to Islam, and objection to military action, which came just as America’s culture wars were boiling over, ensured that even those who cared not a jot for boxing would have reason to look to him as an example.

And so, finally and with a grim irony, would those people across the world living with mental degradation. The blows that rained down on Ali’s head as a boxer took their painful revenge in the form of Parkinson’s, with which he would live for 32 years. Even in this sad final act, his brave public appearances were an unforgettable commentary on a life so well lived, and gave millions, if not billions, someone to look up to.

Of Muhammad Ali, there is little that can be said that he didn't say himself. He was right about the power of sport, he was right about racial equality, he was right about Vietnam and he was right about himself.

He was, as he so often reminded us, the greatest.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments