Gove’s initiative to tackle ‘extremism’ is little more than a distraction

Editorial: The government’s ‘trailblazing definition’ is a solution in search of a problem. If it is to be of any use at all, it will need far wider support and a much stronger sense of purpose

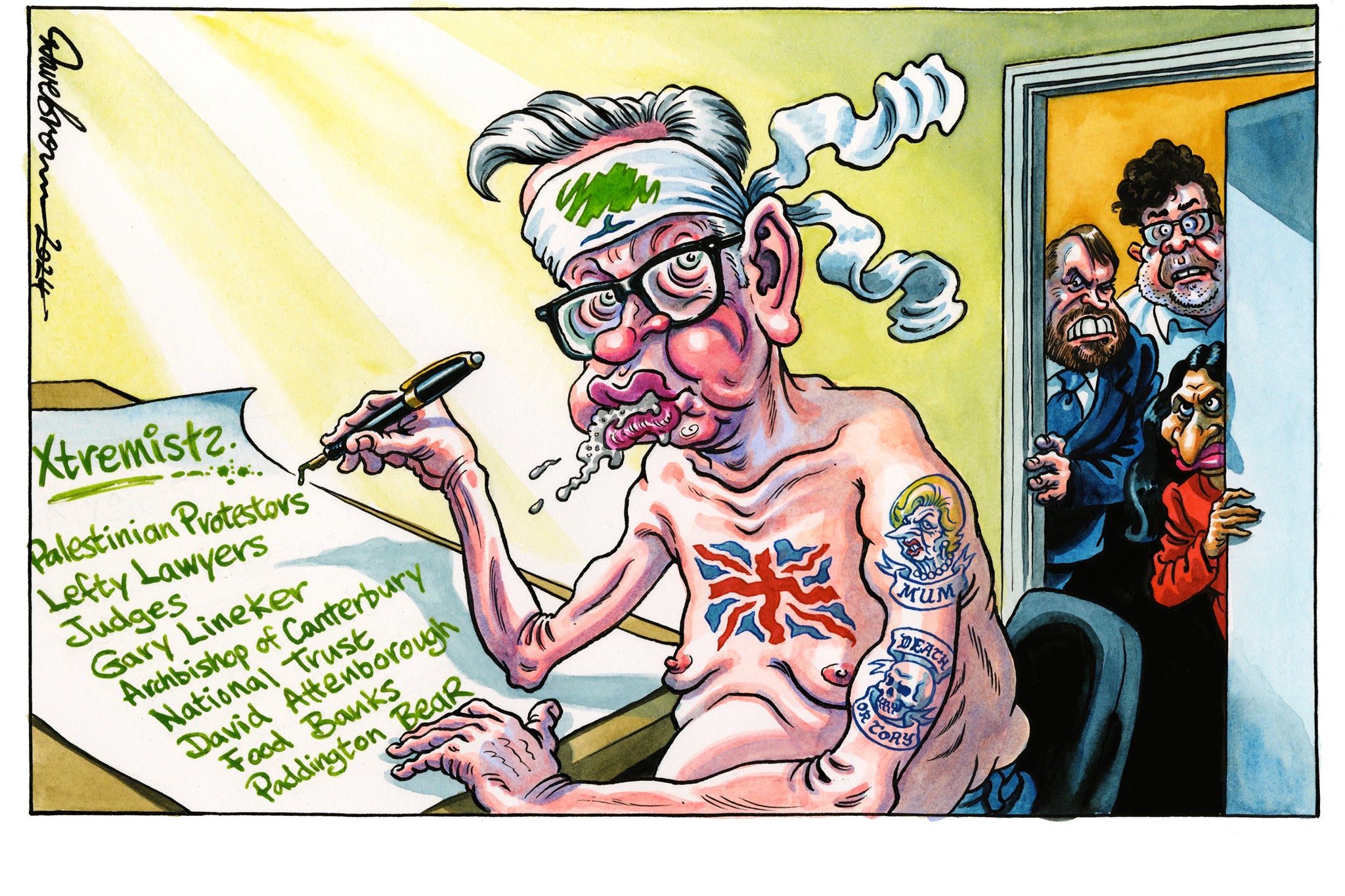

Extremism” is something that (almost) everyone is against, it is impossible to define – and difficult to neutralise. Michael Gove, secretary of state for communities, has made a much-trailed attempt to solve the conundrum of extremism and, in large part, he has failed. To be fair, it is not entirely Mr Gove’s fault because all he has been trying to do is turn the curiously aimless speech Rishi Sunak made on the steps of 10 Downing Street after the Rochdale by-election into concrete policy.

The Rochdale contest was a fiasco, a veritable festival of extremism and the election of George Galloway a minor disaster, but there’s nothing in what Mr Gove proposes that would stop anything like that from happening again. Indeed, it is quite possible that the government’s new approach will do more harm than good: needlessly stigmatising Muslim groups, feeding the victim syndrome and paranoiac appeal of the far right, and generally dragging the kind of identitarian politics that ministers usually deprecate into the centre of political debate.

Mr Gove has issued a list of five groups that could be deemed unsuitable to receive public funds or for the government to “engage” with. He also said they would be investigated over extremism fears.

But his plans have come under criticism from a number of Tory MPs including former home office minister Kit Malthouse who said he “shared some alarm” with fellow members about the extremism definition, as he raised fears that there was no right for a group to appeal their inclusion on the list.

The concern is that if more organisations – or indeed individuals – are added to the list, then it may become disproportionately populated by Muslim organisations and so further fuel Islamophobia, anti-Muslim violence, thus inciting the kind of hatred it should be stopping. Mr Gove’s homilies on the distinctions between Islam as a religion of peace and Islamism as a dangerous and destructive ideology are all very well, but the effect of identifying, or targeting, Muslim groups as extremists, partly on the basis of their views on Palestine, will likely serve to escalate anti-Muslim prejudice.

A cynic might say that the Conservative Party, itself not entirely free of extremist elements, was seeking to open up yet another new front in its “culture war”, and exploit ethno-religious differences as a “wedge” issue with which to confront the opposition parties. It’s a dangerous game – and it is hard to see what possible benefit will arise from this hurriedly prepared initiative.

If the aim is to somehow neutralise and degrade the Palestinian Solidarity Campaign and its regular demonstrations by linking that movement to “extremists”, then it will fail – and deserve to fail – because that very action is an “extremist” action: an attack on free speech, the rule of law and the operational independence of the police.

The new definition of extremism rests on poor foundations. It has clearly been steered by Mr Gove and Mr Sunak, with little consultation outside official circles and a small number of independent (but government-appointed) advisers. That is not necessarily a bad thing – every draft has to start somewhere – but the whole approach lacks the kind of cross-party, cross-community consensus that would help guarantee its durability and wider acceptance. When everyone from Priti Patel to the Archbishop of Canterbury to the Muslim Council of Britain finds Mr Gove’s proposal problematic or even dangerous, then that suggests that it lacks the wide backing it needs to succeed in its objectives.

Therefore it suffers, ironically enough, not because it offends extreme Islamists and neo-Nazis – but because moderate figures and groups regard it as a threat to the very freedoms and spirit of tolerance it purports to promote. In immediate, practical terms, that flaw in Mr Gove’s approach will probably prove fatal, because the inevitable judicial review of the new policy will stymie its introduction until after the general election, by which point Mr Gove and Mr Sunak will be ex-ministers.

The new definition itself is supposed to be more “precise” and superior than the old one, but how this is the case is not immediately apparent. Extremist groups are now defined not in contradistinction to “fundamental British values, including democracy” as laid down in 2011, but instead against those who would “undermine, overturn or replace the UK’s system of liberal parliamentary democracy and democratic rights”.

Well, where does that leave Sinn Fein, which remains the political wing of the Provisional IRA, a body that practised terrorism and which is “extremist” because it is a fascistic group that rejects the democratic rights of people in Northern Ireland, a part of the UK? Does that mean that the UK government will not “engage” with Michelle O’Neill, Sinn Fein’s first minister of Northern Ireland? That the Treasury won’t pay her salary?

Without being flippant, a case could even be made for the Conservative Party being “extremist”, because when Boris Johnson was in charge it sought to unlawfully prorogue parliament and suspend parliamentary democracy during the Brexit battles of 2019. It actively sought to defy the law and deprive the democratically elected Commons of its right to debate and approve the UK’s withdrawal from the EU.

Mr Johnson was an anti-democratic extremist, according to the Supreme Court and was later found to have lied to parliament. He had his own version of an anti-democratic ideology – an elected dictatorship summed up in the slogan “the will of the people”, and a determination to set himself above the law. Perhaps an incoming Labour minister replacing Mr Gove could decide that the wayward Mr Johnson wasn’t somebody the state should engage with or fund, and then deprive him of his post-prime ministerial pension and perks. Joking aside, the scope for partisan abuse of the system is obvious.

The operation of the new definition of extremism is dangerously arbitrary. In a spuriously grand-sounding phrase that could have been lifted from an episode of Yes Minister or The Thick of It, Mr Gove tells us that a new “centre of excellence” within his department will be tasked with naming and shaming “extremist” groups, taking advice from experts. In reality, this will be a group of civil servants in his department making recommendations to him in the usual fashion, with the ultimate decision resting, as usual, with him – a politician with prejudices of his own.

This so-called centre of excellence will not be an independent body free of political coercion or interference – far from it. There will be no administrative right of appeal, only recourse to judicial appeal, which is always the case anyway, and which is expensive to pursue. Some imam who is wrongly or mistakenly identified as a hate preacher will have their reputation destroyed and be subjected to violence because the “centre of excellence” in the Department of Levelling Up, Housing and Communities doesn’t have an appeals department.

Bodies such as the Muslim Council of Britain are within their rights to ask for an opportunity to defend themselves against their possibly arbitrary stigmatisation by a Conservative minister. It will certainly not reassure Muslim people that that party or the British state is sympathetic to the abuse, prejudice and hostility they face.

Extremism is dangerous when it promotes and incites violence, and if and when individuals and organisations do such things they are already breaking the law. As Mr Gove says, the threshold for that is set high, and rightly so. Extremism – which will always mean different things to different people – that doesn’t meet that threshold is best dealt with in the usual way and that is through politics.

There was never anything that forced the state to fund or “engage” with people or bodies it didn’t wish to, for whatever reason, and that includes, for example, the Muslim Council of Britain with which the government has long since broken relations. Mr Gove’s initiative is essentially a solution in search of a problem. If it is to be of any use at all then it will need far wider support and a much stronger sense of purpose. For now, it’s a counterproductive distraction.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks