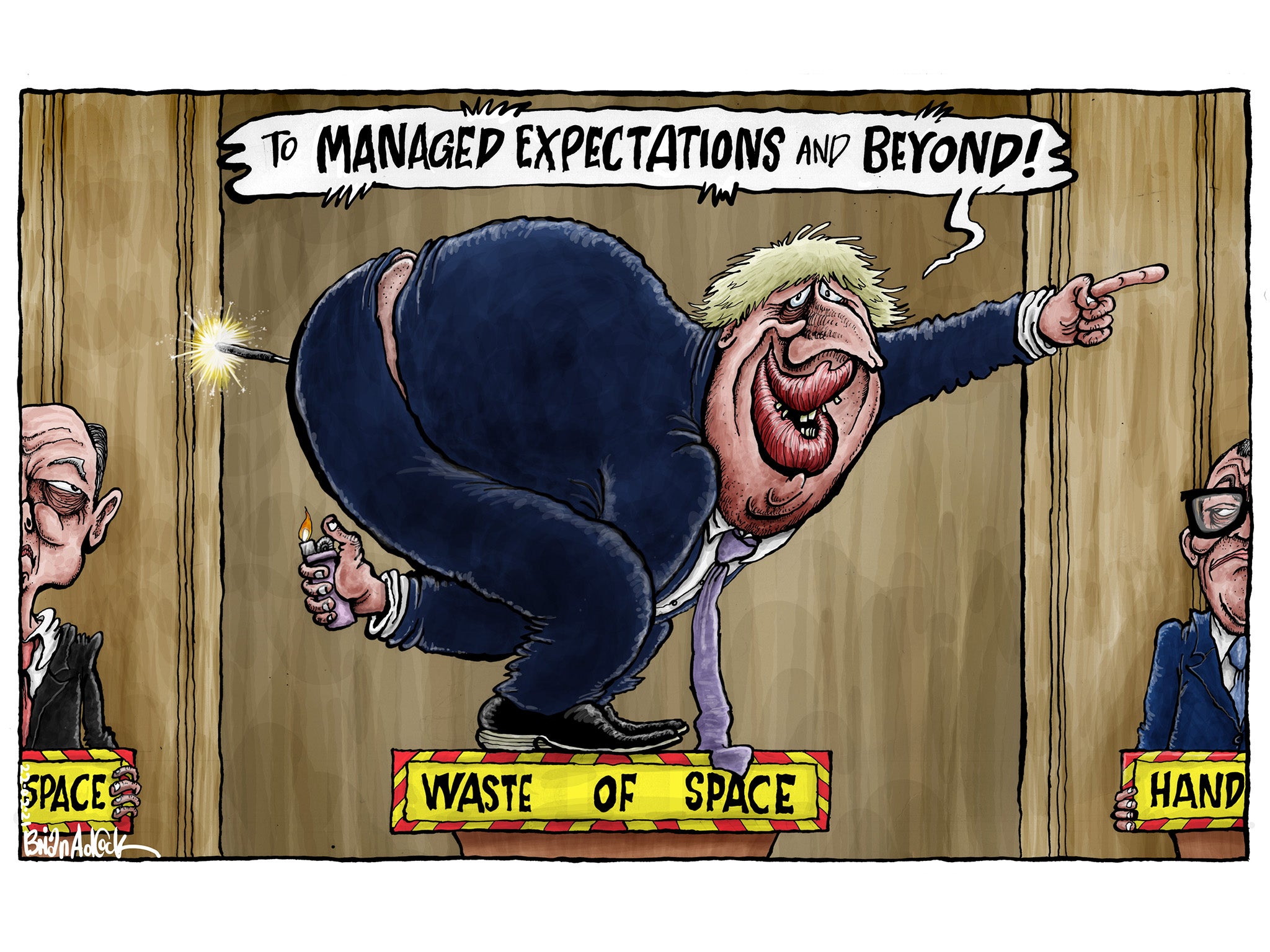

We must be cautious about coming out of lockdown – the prime minister cannot get this wrong again

Editorial: Although the figures for infection and hospitalisation are encouraging, the scientists do not yet know enough about the new coronavirus variants to be bullish about a radical departure from lockdown

The official soundbite over the past few days has been: “Cautious but irreversible.” Lockdown will be relaxed gradually, driven by “data not dates”, to quote another favourite phrase, and this will be the last one. The prime minister’s roadmap promises the route to freedom. Apparently, a game of tennis may be pencilled in for 29 March, and the schools will be up and running by 8 March.

This rather suggests that the lifting of lockdown will be neither cautious nor irreversible. In contrast to the previous cautious noises emanating from ministers, it seems that policy is, in fact, driven by dates rather than data. The schools, with a few caveats, do indeed seem set for a “Big Bang” simultaneous opening on 8 March. (This is in England; Wales, Scotland and Wales indicate a slower and more phased approach.)

Public expectations are being stoked up. This is especially disquieting since there were such strong rumours that the chief medical officer, Chris Whitty, was concerned about this approach – and with good reason. Although the figures for infection and hospitalisation are encouraging, the scientists do not yet know enough about the spread of the dangerous new coronavirus variants to be bullish about such a radical departure from lockdown.

Similarly, while the vaccination programme has been more successful than anyone could have hoped, the full effects on the R rate are also unclear. The early indications are encouraging but the data is not yet strong enough to represent an overwhelming argument.

It will be interesting to see how Professor Whitty, if he appears at the Downing Street briefing on Monday, justifies the policy. It can only be because he has tried to put some safeguards in, or that he has secured a promise that easing lockdown elsewhere will be delayed (in pubs and restaurants, for example).

Even if infection rates were lower and falling faster than they are, there is no compelling reason why schools cannot be opened in waves, perhaps linked to regional performance on the key indicators, as Professor Whitty may have preferred. As has been the case throughout the pandemic, schools have the potential to be hubs for the rapid community spread of the virus, and its more transmissible mutations.

Schools may be “safe”, as Boris Johnson keeps insisting, in the sense that the children do not become ill (yet), but pupils, especially older ones, can infect each other and can give the virus to their families, their friends and thence to their friends’ families. From that familiar exponential phenomenon will come more local outbreaks, and without strong test and trace procedures, those will turn into regional and national epidemics.

Those who work in schools should also still be concerned, for obvious reasons. Given the importance of functioning schools for opening up the economy (because having their children in classrooms liberates working parents), school staff should have been vaccinated long ago, well in time for any reopening in March. Teachers and others working in education should not be placed in danger because ministers can’t face down their more impatient backbenchers and persistent critics in the press – especially when they know they can rely on Labour’s support in parliament.

If easing lockdown is rushed, it merely makes it more likely that the relaxation will have to be reversed and a new lockdown imposed. We have, after all, been here before. Leaving too great a reservoir of virus in the community before the vaccination programme reaches herd immunity levels, and without a working test and trace system, is reckless.

Local, regional and even national lockdowns would then be unavoidable, and much of the hardship and effort of the last few months wasted. Lives will be lost, the economy and the NHS will suffer, again, if the prime minister gets it wrong. This is not a time for his usual senseless optimism, even if it is expressed in more measured terms than usual.

Besides, the pandemic is by no means over globally. Across wide swathes of the world not a single jab has reached the population, and the virus continues to mutate. We know how easily it can move from continent to continent. With or without hotel quarantine, the new variants will get through. It is no good pretending that the English Channel will protect the UK.

As the weather brightens and the green shots appear, there is an understandable and welcome sense of hope in the air, and the balance of probabilities is that the worst of Covid is in the past. But the dangers have not all passed. This is another point of decision that has to be got right. If it is not, or even if the science changes again, a fresh lockdown may become unavoidable in the future.

It is unscientific, to put it politely, for the prime minister to give the impression that there can never be another lockdown simply because he says the current relaxation is “irreversible”. It is anything but.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments