It is a year since Boris Johnson emerged as the unlikely leader of a nation at war, declaring: “I must give the British people a very simple instruction – you must stay at home.”

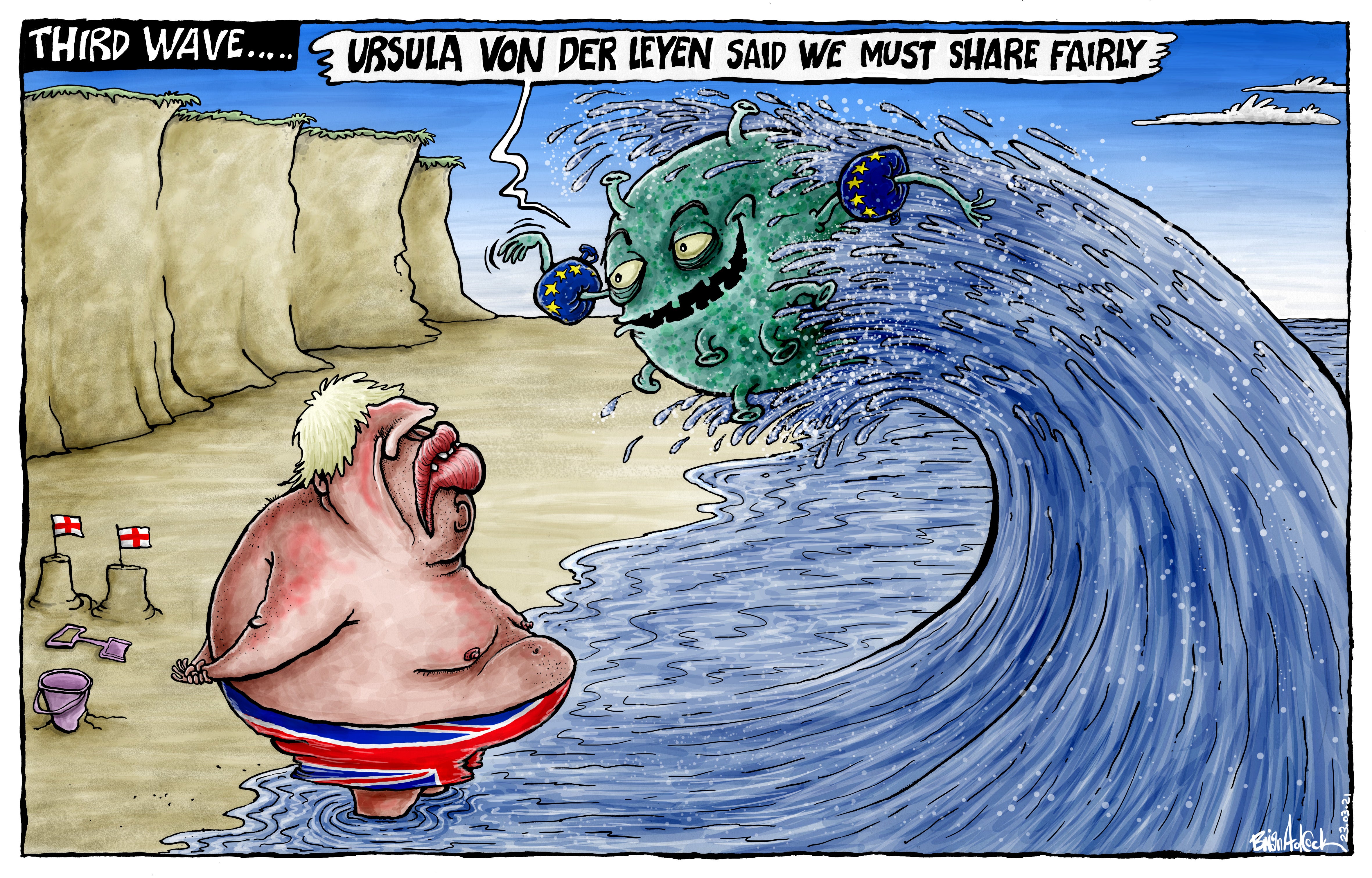

It was the last moment of clarity the nation was to enjoy for some considerable time. Even now, with talk of vaccine wars and “variants of concern”, the future is still uncertain, despite the remarkable progress the NHS and the international scientific community has made in treating, and protecting us against, the fearful disease we came to know as Covid-19.

Human beings are remarkably adaptable, and many of the privations have come to be accepted with stoic determination as the price of eventual freedom and safety. Indeed, the degree to which the “unprecedented” restrictions have been adhered to during their various phases has been stirring (“unprecedented” being very much the word of the pandemic).

It is true that many people have suffered poor mental health, many have faced financial ruin, and others have turned to conspiracy theories, all of which makes the overall mass compliance with the plea to “stay at home” more impressive. There was something of a revival in national solidarity, epitomised by Captain Sir Tom Moore, the “clap for carers” and a genuinely moving address by the Queen. Most people put a mask on, kept calm and carried on. What was lacking was leadership in Downing Street.

If the last 12 months have had a wartime feel to them, with many invocations of the spirit of the Blitz, Dad’s Army or Dunkirk, then there have been some less comfortable parallels with the Second World War.

The first phase of Britain’s battle with Covid, rather like the initial stages of the last global conflagration, was a litany of failures: lockdowns entered too late and exited too quickly; shortages of protective equipment, of ventilators, of testing kits; the neglect of people in care homes; the contracts for cronies; the £22bn blown on test and trace technology that never quite worked; the Dominic Cummings affair; the complicated and ineffective tier system; the dithering about border controls; the school exams fiasco.

It is no wonder that Britain suffered one of the worst Covid death rates in the world. Mr Johnson and his colleagues should never be allowed to live that down.

Read more:

There were many dark hours, but the unalloyed success of the vaccination programme was the happier second part of the story. If the government must take responsibility for the failures of 2020, then it should be allowed some credit for the successes of 2021, the second phase of the war on Covid.

The decision to bypass the usual procurement process for the vaccine, putting production facilities in place before it was developed and approved, and throwing money at the research was decisive: given the tools, the scientists, pharmaceutical companies and the NHS could get on with the job.

Did Mr Cummings, as the prime minister’s forceful adviser, play some part in the breakthrough by cutting through the usual bureaucracy, as he suggests? If so, then that should be weighed against his earlier selfish irresponsibility in the famous drive to Barnard Castle, which rightly enraged so many.

After his own brush with Covid, with his partner expecting their child, Mr Johnson won a great deal of personal sympathy, yet many were increasingly exasperated by the incompetence of his administration. Only the furlough scheme and other huge support given by the Treasury and the Bank of England, with parallel moves globally, saved the economy and the government from collapse. The prime minister’s political survival was also a close-run thing.

When Mr Johnson made his grim televised address a year ago, he gave the vague impression that the lockdown might not be for long: “I can assure you that we will keep these restrictions under constant review. We will look again in three weeks, and relax them if the evidence shows we are able to.” That was merely the first of many false dawns. So here we all are, still, staying home if we can.

Had the vaccines not arrived when they did, in record time, and not been rolled out as rapidly as they have been, then it is entirely possible that the public finances might not have been able to support the economy at the same level for another year or longer. That would have left the nation with the appalling prospect of the NHS being overwhelmed, a fate that at times was only just avoided in any case.

It is no disrespect to anyone’s grief to reflect that this pandemic could have been even worse than it has been. Even so, it was not Mr Johnson’s finest hour.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments