Labour and the Tories must stop avoiding the difficult issues

Editorial: As the two main parties prepare to unveil their manifestos, the time has come for a more candid debate about how they will tackle the biggest problems facing this country

When the political parties unveil their manifestos this week, they have an opportunity to engage voters who have not yet tuned into the election and might not do so. Worryingly, a survey by Techne UK for The Independent found that 20 per cent of people have already decided not to vote, and some experts think we might see the lowest turnout in modern history.

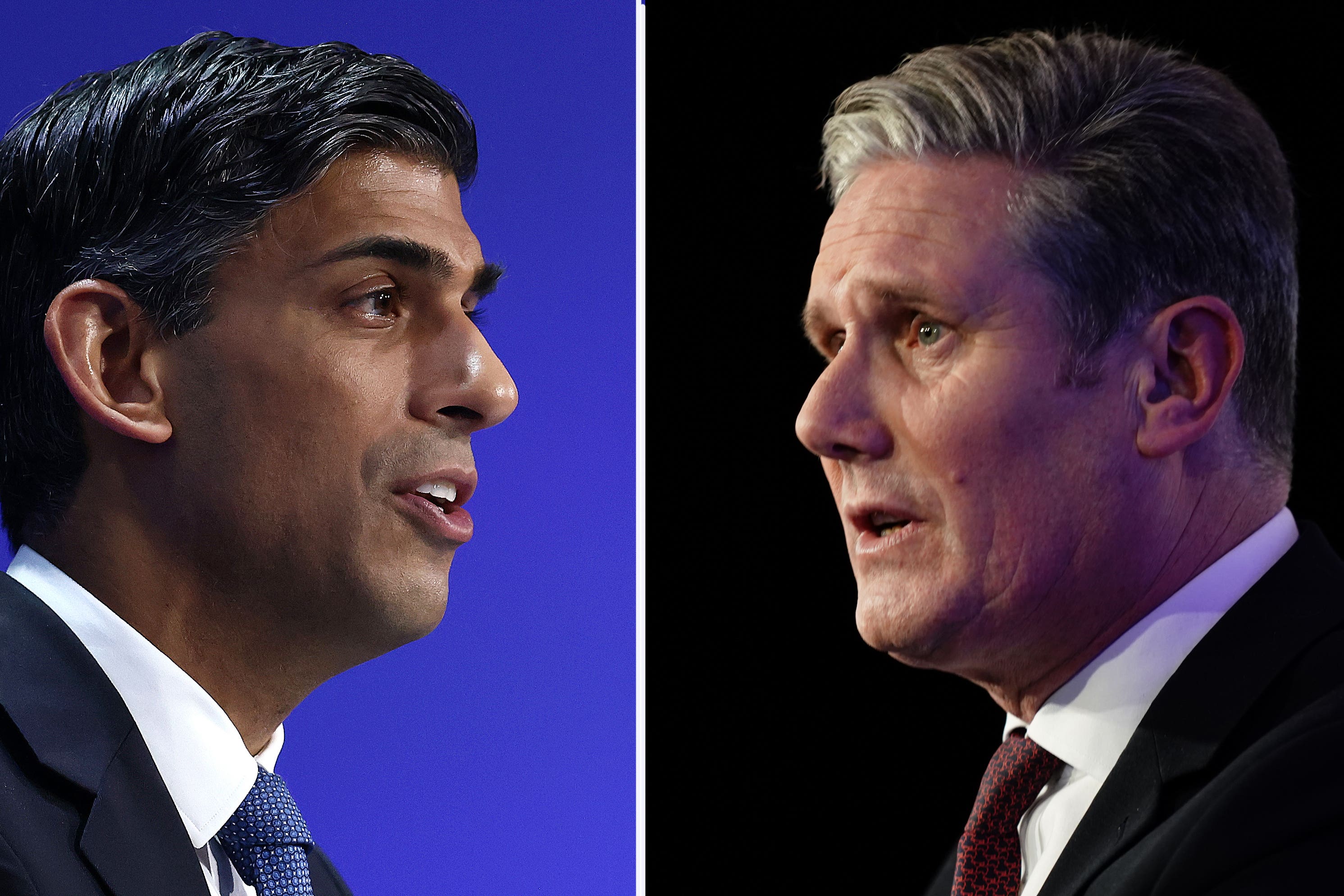

That would not be a surprise given that many voters have written off Rishi Sunak and the Conservatives but have not yet been won over by Keir Starmer’s Labour Party. Labour’s 20-point opinion poll lead has encouraged Sir Keir to run a safety-first campaign. So far, the Tories appear to be appealing to their core vote to limit the scale of the defeat they expect on 4 July, rather than talking to the whole country.

Naturally, all parties want to play to their strengths and attack their opponents’ weaknesses. But this has resulted in a very narrow election agenda, contributing to a lack of excitement about the election and the absence of much hope for a better future. The manifestos offer the parties a chance to have a more honest conversation with the public about the huge challenges facing the next government. If they take it, more people would probably turn out on 4 July, which would be a good thing.

The public would take more notice if the parties took several issues out of their “too difficult” box. Brexit has barely featured in the election debate; the Tories do not want to remind voters of their part in this act of economic self-harm, and Labour does not want to talk about its plans (which are more ambitious than it lets on) to remove trade barriers because the Tories would accuse Sir Keir of attempting to rejoin the EU via the back door. A more grown-up approach by both parties would be welcome.

There is also a “conspiracy of silence” on post-election public spending, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies. Tuesday’s Tory manifesto will doubtless include more pledges to cut taxes, even though Jeremy Hunt’s double reduction in national insurance failed to move the polls. Labour will offer a cast-iron “triple lock” pledge not to raise income tax, national insurance or VAT, as the Tories have also promised. Labour might come to regret its pledge.

Both the Tories and Labour are reluctant to talk about the £23bn a year of tax rises already in the pipeline, as the freeze in allowances and thresholds will continue until 2028. They prefer the warm fantasy world of tax guarantees and locks, and suggestions that taxes will come down.

Although both parties know our crumbling public services require urgent investment, they have put on an unnecessarily tight straitjacket by their tax pledges and fiscal rules. The current government’s implausible plans envisage about £20bn of public spending cuts over the next few years. Although overall spending is due to rise by 1 per cent above inflation, existing commitments to boost the budgets for defence, the NHS workforce plan and childcare mean other areas – including the police, prisons, courts and local government – face cuts of 2.6 per cent in real terms by 2028-29, according to the Institute for Government think tank.

The two parties’ stances do not reflect the public mood: eight in 10 people believe that services are in a bad state and more people prefer more spending even if it means them paying more in taxes. Yet there is little discussion about the inevitable trade-offs.

Both parties say they would fund some spending pledges by promising to reduce tax avoidance, which cannot be guaranteed. They would square the circle by securing higher economic growth – not bankable, and dependent on the global economy as well as domestic policies. There is much talk of public sector reform and new technology does offer real hope of efficiency savings, but again that is not certain.

The straitjackets have limited the election debate on the cash crises looming for many councils and some universities, and for vital services such as social care (with the honourable exception of the Liberal Democrats, who have promised free personal care for adults in England). Regrettably, a paltry debate on climate has been hijacked by the Tories to attack Labour’s measures to decarbonise electricity generation, and there is little discussion about how to achieve net zero. We have not yet heard how the parties would regulate big tech and social media.

The narrow debate stemming from the unholy Tory-Labour alliance could enhance support for the smaller parties, including Nigel Farage’s Reform UK, reducing the big two’s combined share of the vote. Perhaps Labour would not lose much sleep over that as long as it regains power. Yet for democracy’s sake, both Mr Sunak and Sir Keir owe the public a more open debate than we have seen so far, and more candour about how they would address the daunting in-tray awaiting the next government.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks