Morality doesn’t play much of a role in politics, and never has, so it’s a little fatuous to object to the chancellor’s fiscal plans on purely moral grounds. Politicians tend to be more like bookies than bishops.

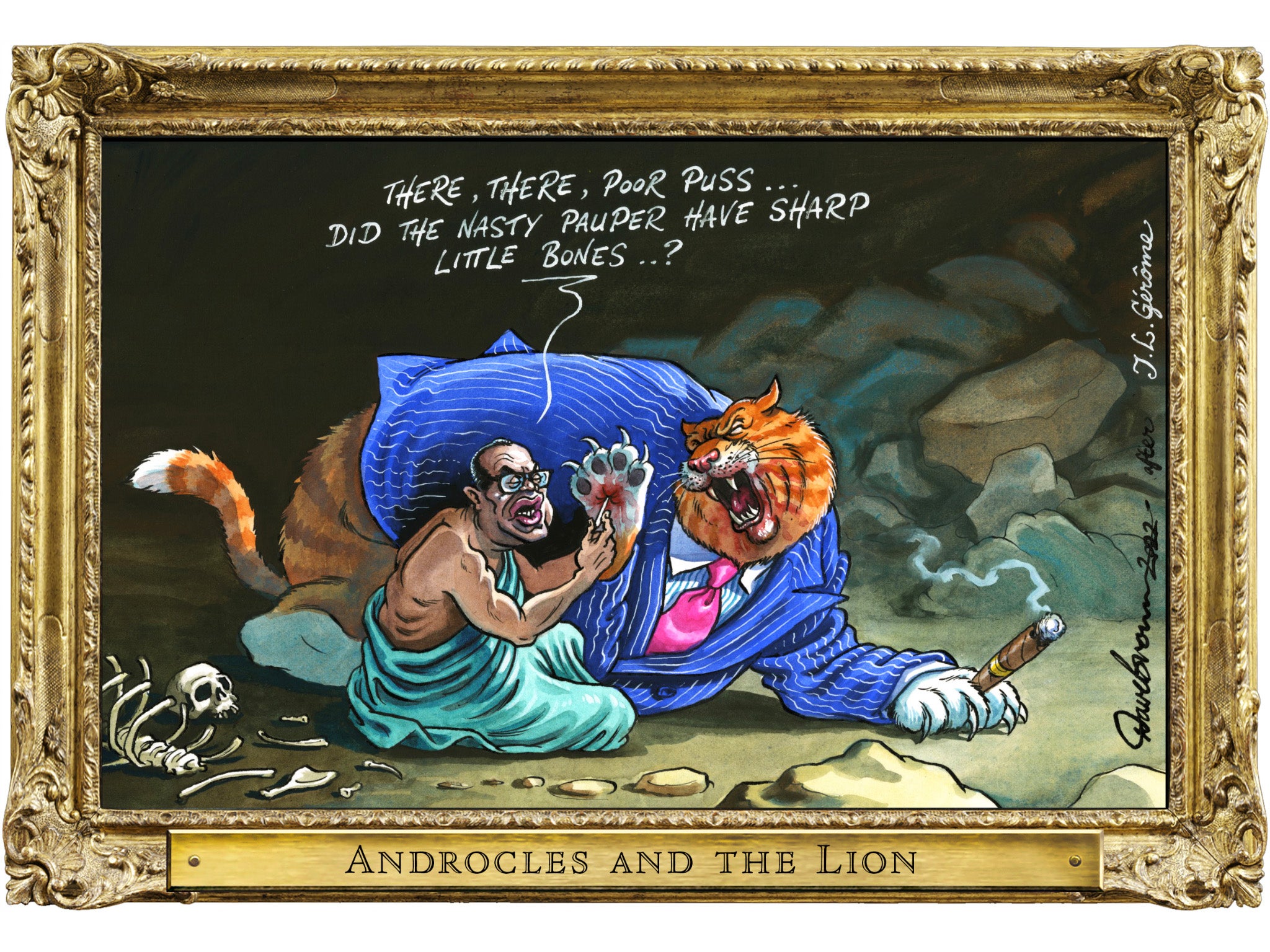

Kwasi Kwarteng certainly doesn’t seem to spend much time contemplating social justice; indeed, he explicitly renounces what he thinks has been an undue emphasis on “fairness” and distribution in recent times, with too little attention paid to growing the “cake” in the first place. Hence his audacious tax cuts for the already rich, at a time when poor and middle-income families continue to struggle with the cost of living crisis.

This is indisputably unfair, indeed obscene. It marks a clearer dividing line between the government and the opposition parties. Even with the welcome intervention of the energy price guarantee, gas and electricity bills are still set to double for households, with similar hikes or worse in prospect for businesses in the medium term. Britain is to be an even more unequal society.

The majority of the British people will see the mini-Budget for what it is: perverse and ideologically driven, and callous with it. They are right to do so. The principle that those with the broadest shoulders should bear the cost of economic adjustment is well established. Renouncing it is no vote-winner. The budget is unlikely to help the Conservatives’ poll ratings, certainly not in the short run.

Yet the more pertinent question is not about fairness or morality. It is the one Mr Kwarteng himself poses: whether the chancellor’s plans will indeed put Britain on a path to sustainably higher growth.

To listen to Mr Kwarteng, you would think that it is only the rich who respond to incentives and economic opportunities – and that they are in some sense the economic victims of recent events. This hardly bears scrutiny.

Those who work in the City are not, on the whole, having to cope with miserable real-terms pay rises. Nor are they migrating to Paris or New York. Yet the cap on their bonus payments – designed to discourage reckless behaviour – is about to be lifted.

To take another gratuitous example: Mr Putin’s war in Ukraine has accidentally turned the energy giants into cash-generation machines, yet their excessive windfall profits are to be left unchallenged – even as they virtually invite the Treasury to help itself to a slice of the action.

The new tax cuts favour those with considerable wealth already accumulated in business assets, who are relatively well hedged against rising inflation. Lucky and unusually well-heeled first-time buyers acquiring their £625,000 starter home will be given a windfall of some £11,250. It is not immediately obvious how this converts into a boost for productive private-sector investment.

Similarly, tax and national insurance cuts will disproportionately benefit the wealthy – those on social security, who pay neither income tax nor national insurance, will not see any amelioration of the financial squeeze. If Mr Kwarteng wants to boost the economy to avoid recession, he should give the money to those less well off, who are more likely to spend it than save it.

If he wants to induce investment, then the funds should have been targeted more explicitly in that direction. He might have usefully subsidised “green” energy and insulation schemes. But, like the now forlorn cause of “levelling up”, the transcendent challenge of climate change found no mention in the plan for growth.

Besides, it will all be futile if the Bank of England ramps up interest rates to cope with the resulting inflation; the economy will enter a recession in any case, albeit after the Kwarteng boom turns to bust.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

Where is the encouragement for those on average and below-average incomes to work harder and save more? To enter the job market or start their own businesses? It is scant indeed. Mr Kwarteng’s idea of an incentive for workers earning £10,000 a year or so is to cut their benefits in an attempt to push those who cannot work into jobs in places far away, or to which they are unsuited.

The chancellor seems to have a vague inkling that his dash for growth won’t get very far in an overheating economy with too few workers. Many EU workers have returned home post-Brexit, and others (the Bank of England suggests 400,000 people) are suffering from long Covid. This is a far greater figure than the 120,000 people Mr Kwarteng is going to force to work harder.

This is a mini-Budget that will be funded by borrowing. It will stoke inflation, push interest rates higher, and eventually turn to bust. It is unsustainable, and therefore cannot succeed in its stated intentions, because in due course all of the tax cuts will need to be reversed, or else public services cut – and either way, it will be bad for private businesses.

The spike in gilt yields suggests that City bankers have no faith in the chancellor’s growth plan. Given that Mr Kwarteng has just uncapped their bonuses and cut their taxes, you’d think they’d be a bit more grateful. He’ll be hoping for more from the voters.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments