North Korea's latest missile strike has shown that Kim Jong-un might not be that mad after all

For reasons that remain obscure, the Japanese chose not to shoot down the missile as it passed through their airspace. If Kim was testing the resolve of his nervous neighbours he found them, satisfyingly for him, weak

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

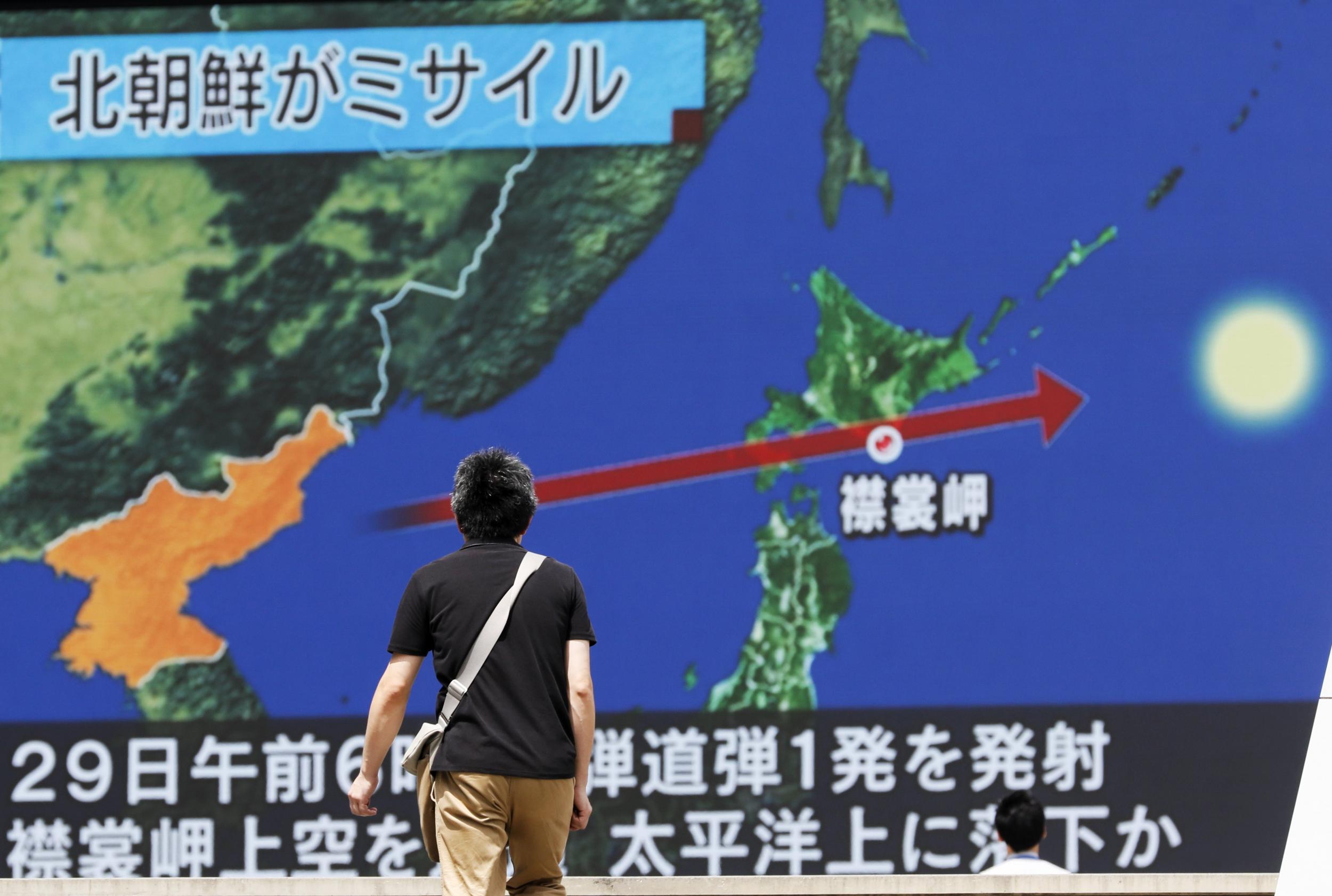

Your support makes all the difference.Kim Jong-un, the still youthful ruler of North Korea, is usually dismissed as dangerous and a “madman”. The latest missile strike into the waters of Japan, passing as it did over populated areas of Hokkaido and triggering sirens and some alarm, shows that, whatever a psychiatrist might make of him, Mr Kim has the capacity to fashion his interventions with impressive skill and judgement. In that respect, at least, he stands firmly in the tradition of history’s worst despots, who combined genocidal instincts with tactical gifts. Dangerous, in other words, but maybe not mad.

In pulling back from a direct threat to US sovereign territory in Guam, for example, Mr Kim showed that he has some sense. To have fired a missile at Guam would have been too direct a hit on the United States, and, moreover, to Donald Trump’s pride. Some kind of military retaliation, in other words, from the White House was a risk too far. On this occasion it was preferable to go for a proxy, and to menace the Japanese, hamstrung as they are by historic treaty obligations to run a pacifist foreign policy, although one backed with one of the planet’s more substantial “self-defence” forces. For reasons that remain obscure, the Japanese chose not to shoot down the missile as it passed through their airspace. If Mr Kim was testing the resolve of his nervous neighbours he found them, satisfyingly for him, weak.

History, too, means that the strike towards their former imperial occupier Japan, still hugely resented, is even more popular in North Korea than one against the hated Yankees. The fact that another major power is involved also complicated the response of the White House, which is in any case preoccupied with the crisis in Texas and Louisiana. Mr Kim’s timing and choice of target was judged correctly; there will be no immediate response from his enemies. South Korea and Japan have asked for nothing more than words and economic action against Mr Kim, and cautioned the US against precipitating another war.

Hence the routine referral to the United Nations Security Council, yet again the world’s major powers will condemn the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and discuss tightening still further the sanctions on the regime. Theresa May, visiting Tokyo, will be able to remind Japan that not only is the UK an important economic partner that asks for cooperation and support during Brexit; but the UK is also a firm ally and friend on the Security Council. In their different ways, both Ms May and her counterpart Shinzo Abe need to rally friends around the world right now.

Britain, though, is not going to tip the balance of power in East Asia. As in all the many previous versions of these diplomatic rituals, the real influence, if not power, over Pyongyang isn’t going to be derived from Washington, currently banning the last US package tourists from visiting the country (who might well themselves qualify for the term “mad”). It is going to be wielded by China, which takes 90 per cent of North Korea’s exports. This time China has issued an unhelpfully even-handed response to the latest DPRK stunt, condemning the US and South Korean pressure on North Korea, and calling for dialogue, something that has never yielded much reciprocity from three generations of the Kims.

China, to be sure, looks aghast at its wayward and wilful neighbour, and would probably want nothing more than for Mr Kim and his regime to follow the Chinese route to reform and semi-capitalism. Fear of being pushed down that road by his superpower friend, or being deposed in favour of a more docile and China-friendly figurehead, was the alleged motive for Mr Kim having his half-brother assassinated at Kuala Lumpur airport earlier this year. His fun-loving sibling had been living under Chinese “protection” in the casino province of Macau, and could conceivably have been installed in a coup. That too might have been a favoured Chinese solution to the Kim problem. Paranoid or not, Mr Kim has now closed off that particular option.

However, worried about Mr Kim as they are, China’s rulers also fear war on the peninsula, millions of Korean refugees and, still, more, the presence of American troops on the Chinese border. Brutal and unstable as Mr Kim is, Beijing prefers him to any realistic alternative. They may glance to Libya and Syria to see what chaos can happen when a strongman falls from power. Beijing no doubt would like to help Mr Trump, but not at the expense of its own security, and the President’s fulminations about Chinese economic policies haven’t helped relations.

South Korea, after the recent elections, has also a government that favours a softer approach to Mr Kim, and, with Seoul only 35 miles from the fourth largest army in the world, has more to lose than anyone from a military escalation. The last player in this great game, Russia, is also presently disinclined to do Mr Trump any favours.

So President Trump has less reliable friends than he would wish for in trying to tame Mr Kim. Like his North Korean counterpart, he will need to be tactically cunning as he contemplates his next move. The chances are that he will follow the unfortunate policy set by presidents George W Bush and Barack Obama – to speak harshly and carry a small stick. It didn’t work for them, as Mr Trump has rightly said; but he will find it the only practical option left on the table. He has been outfoxed by a madman.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments