Wealth creation is Starmer’s bold central pledge from which all else follows

Editorial: If Labour can fulfil the promise of an early boost in growth by raising investment and cutting the tax burden, then the ‘decade of national renewal’ will become a reality

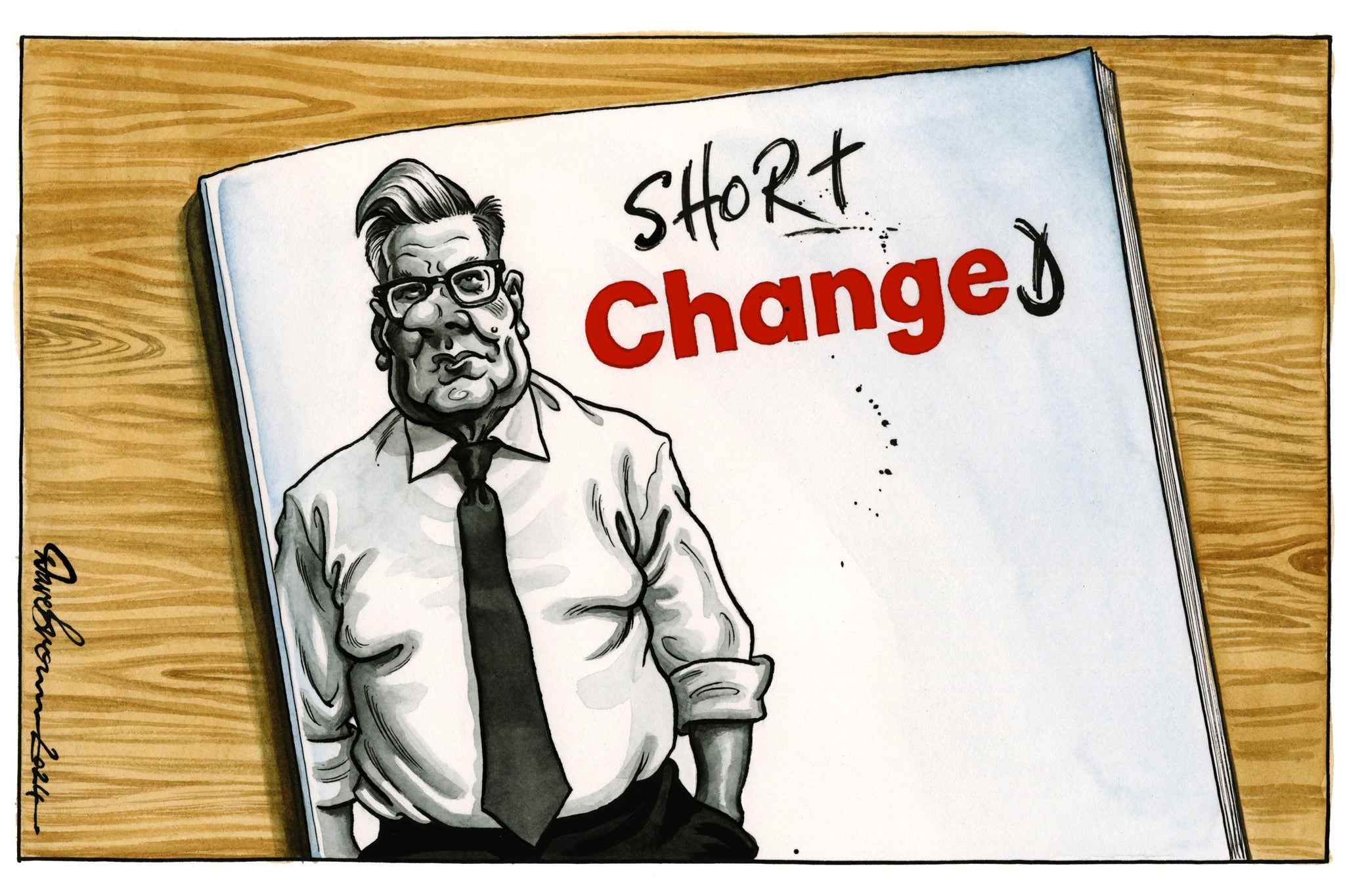

Though the sober-looking monochrome figure looking out from the cover of the Labour manifesto doesn’t resemble anyone’s idea of a revolutionary, there is no doubt that Sir Keir Starmer has not just changed his party’s policy and presentation, but also its philosophy.

In his own words – and he dominates his party as no leader has since the “sun king” phase of Tony Blair’s reign – “wealth creation is our number one priority, growth is our core business”.

Rather like his endless references to his father’s occupation, Sir Keir seems determined also to get the message through that Labour is now “the party of wealth creation”. The term “redistribution” was only uttered to invoke Labour’s misguided priorities in the past.

It is difficult to believe that only a few years ago this party was led by Jeremy Corbyn, with a consciously old-fashioned socialist programme. We may have come to take it for granted, but the recent transformation in the party and its fortunes has indeed been led by Sir Keir, and it has represented a revolution. When Labour is set to win scores of seats in places held by the Conservatives for a century or more, that in itself is a testimony to the efforts of all those involved in its rebuilding.

Sir Keir was very clear that there would be no surprises in the manifesto, no “rabbits out of a hat”, as he put it – and so it proved. An unkind soul might say that Sir Keir, this understated revolutionary, is so keen to reassure the nation that he is boring his way to power. But that in itself is a radical change from the past. The manifesto contains few hostages to fortune, and the leadership has tried not to make pledges they cannot honour. It is designed to be credible, sustainable, believable.

That, however, does not mean that the Labour programme doesn’t contain challenges and assumptions that are themselves risky. The almost blanket pledge not to raise any taxes to implement the measures outlined in the manifesto leaves very little room for manoeuvre for the likely next chancellor, Rachel Reeves. She apparently wrote the relevant parts of the manifesto and its costings, so she will only have herself to blame if she eventually has to bend some of her iron-clad rules.

She may well have to do so. The first reason is that, as every expert points out, Labour seems set to accept most of the present government’s plans for public spending in the coming years – plans that imply substantial real-terms cuts in unprotected public services and probably inadequate extra funding for the NHS and social care.

During this election campaign, there has also been precious little debate about the looming financial collapse of local authorities and universities, which will surely have to be so rescued by central government. Within months of moving into the Treasury, in other words, Ms Reeves could be faced with unprecedented demands for assistance to prevent local councils and universities from going bust. These are certainly not covered in the Labour manifesto.

The second cause for concern is that it is not clear how all the laudable supply-side reforms proposed by Labour will necessarily yield the increase in growth that will underpin improvements in wages and public services, and keep taxes and debt as a proportion of national income under control. How will planning reforms, Great British Energy, the National Wealth Fund and the rest “kickstart” growth?

Labour, it seems, will borrow to invest – but how much and when remains opaque. It will be constrained, in any case, because the Labour government – if elected – will only borrow to invest consistent with debt falling between years four and five of the rolling Treasury forecast horizon. After the £28bn green new deal was almost entirely scrapped a few months ago, only relatively modest pump-priming schemes to boost infrastructure investment remain.

It is unfair to expect any government in post-Brexit Britain to rapidly tackle historic challenges of low investment and meagre productivity growth. Trade barriers with Europe deter investment, and the debt overhangs from the global financial crisis, the pandemic and the energy crisis leave little room for ambitious borrowing, or even for investment. Liz Truss, like some other Conservative prime ministers in the more distant past, taught the nation a timely lesson in what a reckless dash for growth can lead to.

Yet that early boost in growth is precisely what Sir Keir is promising. It is his one bold central pledge – wealth creation – from which all else follows.

If he, Ms Reeves and the rest of the putative next administration can fulfil that promise – and begin to raise investment and cut the tax burden – then the “decade of national renewal” Sir Keir talks about becomes a reality, and with it the prospects of a second term.

For now, he has his work cut out to make his first term a success in such straitened times.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks