The Tories should focus on policies, not the age of their leader, if they want to win the youth vote

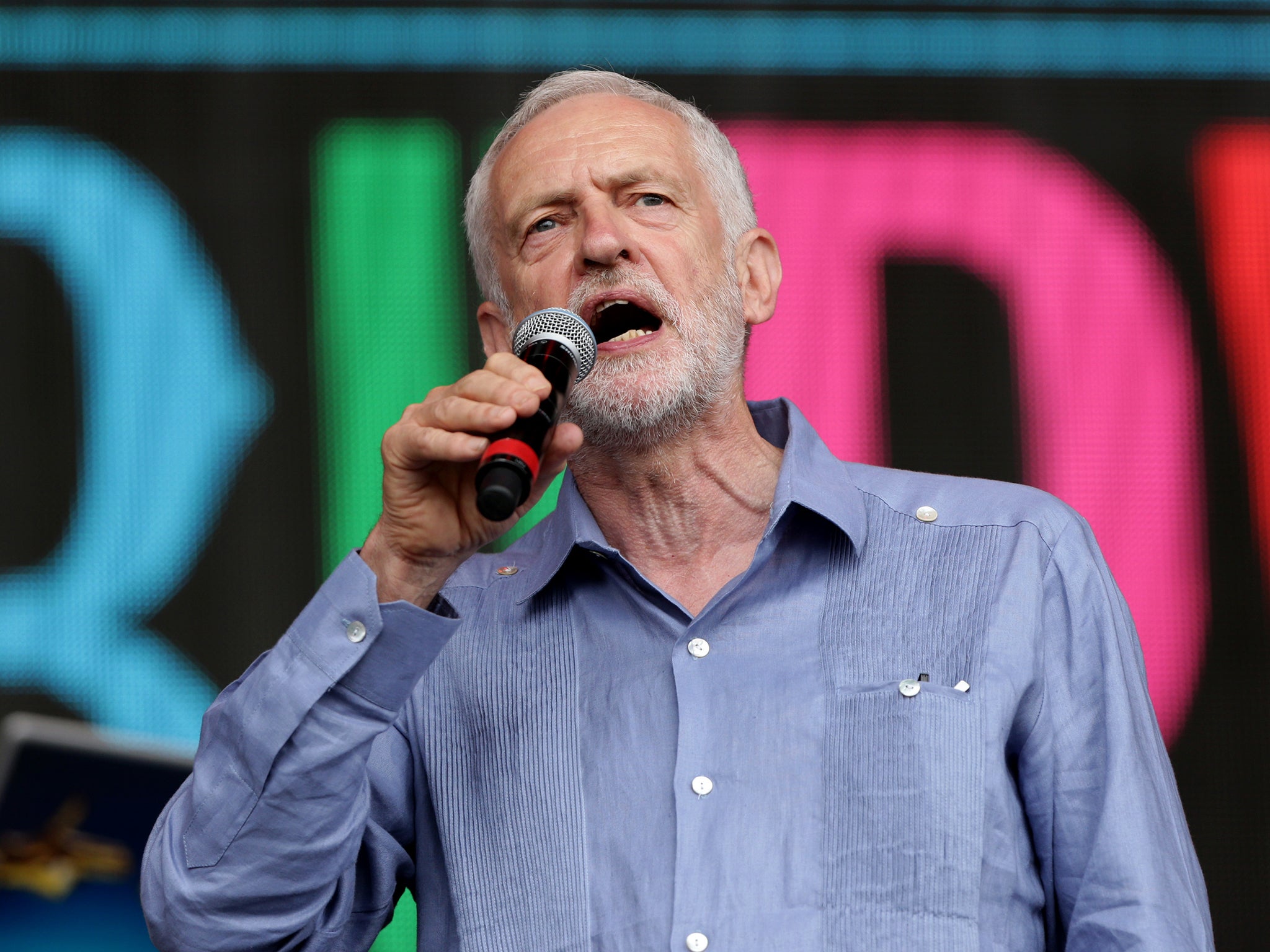

Jeremy Corbyn has spoken to the needs and frustrations of young people, proving they can connect with politicians of any age if they feel listened to

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The sight of the 68-year-old leader of the Her Majesty’s Opposition being celebrated by the revellers at Glastonbury will have been encouraging to other people beyond the usual age of retirement, proving they can still connect with the British youth. In Shakespeare’s poem “Crabbed age and youth cannot live together”, but maybe Jeremy Corbyn can show how they can. Certainly our 91-year-old Queen was better able to connect with the victims of Grenfell Tower catastrophe than our 60-year-old Prime Minister.

But of course age and youth must live together, and one of the core challenge for politicians of all shades of opinion, and indeed all ages, is to generate greater opportunities for the young. Objectively the plight of young Britons may be better than their counterparts in much of the European Union – that is why so many young Europeans have come to the UK to complete their education or seek work – but that is not the way it feels. A generation facing stagnant real wages, unable to buy a home, and saddled with student debts, has reason to be angry. This is something that successive UK governments have failed to tackle and the present government has found hard to acknowledge.

Suggestions that when the Tories do replace Theresa May they should skip a generation and elect someone much younger than the present leadership contenders show that they may at last have appreciated the gravity of their failure to win the young vote. But changing a leader is no substitute for changing policies.

This paper has argued that the Labour response, as set out in its manifesto, while attractive in many regards, was based on unsustainable spending plans. The sums did not really add up. But the appeal remains enormous, and though this Government is preoccupied with the Brexit negotiations it must make a start in tackling the concerns of the next generation. That is assuming it survives long enough to do so.

There are no quick obvious wins, but there are number of key areas where the Government can and must make a start. David Willetts, the former Conservative universities minister, now chair of the Resolution Foundation, has set out an agenda. Top of the list is to build more homes. It is widely appreciated that the boom in house prices has given the baby boomers, born between mid-1940s and the early 1960s, a huge windfall in wealth. Less well know is that quite small differences in the year of birth creates large differences in life chances.

For example an adult born between 1980 and 1985 has on average half as much wealth at the age of 30 than one born five years earlier. Baby boomers have half the wealth in the country; millennials, born between the early 1980s and mid-2000s, have just 2 per cent. Building more houses and flats would not tackle wealth inequality directly, but by increasing the stock of housing it would help to curb the rise in house prices. Over time it would enable more millennials to own their own homes, and build up some housing wealth too.

University tuition fees must also be tacked. Whatever view one takes of the fairness or otherwise of the English system, the interest charged on student debt is too high in the present world. The idea mooted by Mr Corbyn that student debts should be written off is hardly likely to become policy under any government, including a future Labour one. But the present system is unsustainable and the Government knows it.

The greatest challenge, however, is to improve education – and access to education – at all levels and for all people. The present generation of young working people are competing not only against their contemporaries in Europe – whatever happens in the negotiations, movement of jobs between the UK and the EU will continue. They are competing directly or indirectly against their peers throughout the world. Education is the key, and it is the responsibility of each generation to ensure that the next one is better equipped than it has been. Those who, through the good fortune of their date of birth, have done well out of economic growth, need to find ways of recycling some of that wealth towards the following less fortunate generations. That way, to adapt the next line of Shakespeare’s poem, youth will be more full of pleasance, and age less full of care.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments