The art of making a Budget in hard times – and the next few years will remain challenging for both the public finances and the wider economy – is to make a little go a long way. This the chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, has succeeded in doing.

He had a little room for manoeuvre because the emergency measures he took at the end of the chaotic Truss-Kwarteng experiment last year have already begun to yield some relative improvements in the cost of borrowing, and the funds have mostly been used wisely and in targeted fashion on nurturing new industries and getting people back to work. However, whether these measures will in due course deliver the kind of prosperity he promises – or indeed, rather sooner on the horizon, a further term of Conservative government – is a matter of some uncertainty.

Some of the headlines generated by Mr Hunt’s statement amount to unalloyed good news, and – after the traumas of the recent past – are worth cherishing. Most important, inflation is projected to fall even faster this year than expected, from almost 11 per cent on the CPI measure to 2.9 per cent by the end of the year. This is not only obviously laudable in its own right, but indicates that the dreaded wage-price inflation spiral has not taken hold. That, in turn, should give the Bank of England scope to ease the upward trend in interest rates, and see them moderating next year.

The public finances also look to be improving, but only in the context of the wartime-like levels of state borrowing during the pandemic. A fall in wholesale energy costs makes an extension to the energy price guarantee affordable. The national debt, as a proportion of national income, will eventually start to nose down, albeit marginally and not before 2027-28 – and will remain close to 100 per cent of annual GDP.

The 2024 technical recession may have been “cancelled”, in the sense that the economy won’t shrink in two successive quarters, but it will be bumping on and around the bottom for the whole year, and output will still decline by some 0.2 per cent overall. Buried away in the Office for Budget Responsibility paperwork is the revelation that real disposable incomes for British households will fall by 5.7 per cent this year and next – the biggest drop in living memory.

Things are undoubtedly better than they would have been in the barely imaginable nightmare parallel universe where Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng were somehow still in post, but that’s nothing to crow about, and Mr Hunt, wisely and politely, didn’t choose to bring back bad memories. The planned freeze in personal tax allowances, unmentioned by Mr Hunt, will still cost between £500 and £1,000 a year for basic-rate and higher-rate taxpayers respectively. Success, in the current post-Brexit post-pandemic environment of slowish growth and a huge debt overhang, is a relative metric.

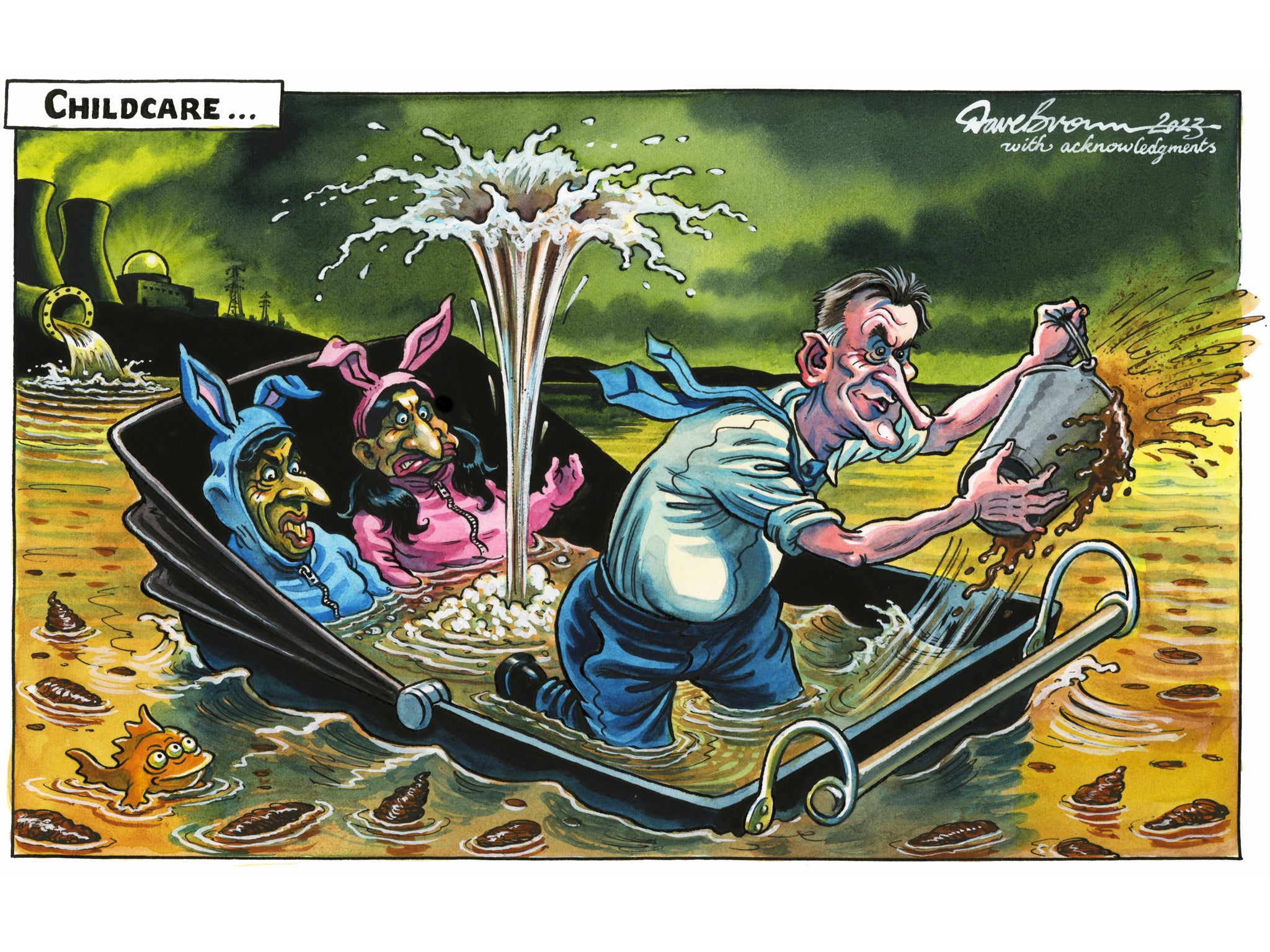

Within the tight macroeconomic constraints, Mr Hunt showed some flair, imagination, and optimism, as well as a willingness to present some hard truths about the immediate prospects. Even if his chancellorship proves short, he deserves to be remembered for the radical changes to childcare provision he has managed to carve out of his limited means. He has combined more financial help for working parents with additional funds for nurseries and schools, and an adjustment in the carer:child ratio such that far fewer mothers and fathers will have to stay at home or go part-time to take proper care of their children. That will boost the economy as well as intellectual development, and help to reduce the gender pay gap as well. Win-win-win.

Much the same goes for the pension tax reforms. It is true that they are most helpful to the highest earners, but it is difficult to see how else the disincentives to working affecting highly skilled and productive professionals could be swiftly removed. Nowhere is this more obvious and pressing than in the loss of experienced, brilliant physicians working in the NHS. Now more than ever, they are needed on the wards and in the surgeries, and, as with the nurses and junior doctors, if the country wants high-quality healthcare, it needs to fund it.

Which raises the great omerta of the Budget – public pay. It is at least debatable as to whether Mr Hunt should have cancelled, as he did, the usual increase in fuel duty of 5p per litre, among other measures, rather than finding some extra money for settling the strikes in the NHS. Perhaps, in the middle of the junior doctors’ three days of industrial action, Mr Hunt and Rishi Sunak judge that they are winning the battle, if not yet winning over public opinion. It is, though, a missed opportunity.

In the big scheme of things, a few billion thrown at the quest to make the UK a leader in the artificial intelligence revolution is probably worth the punt, as are the various wider incentives for business investment – which will be more effective in raising productivity than simply cutting corporation tax rates.

There was shameless populism, too. After a long absence, “levelling up” made a comeback: there was that freeze in fuel duty, a cheaper pint in the pub, and cash for fixing potholes and crumbling municipal swimming pools. Many of these measures looked suspiciously like they were aimed at marginal seats held by Conservatives in the Midlands and the North. Even so, public spending, projected to rise by just 1 per cent a year, will inevitably mean another round of austerity and pay restraint in the public services. Mr Hunt didn’t dwell on the implications of that.

Mr Sunak and Mr Hunt have shown themselves to be an effective partnership and, projecting calmness and competence, are determined to show that their plan is “on track”. Politically, the questions are clear. Are we out of the woods? No. Is the worst over? Almost; and next year – election year – should see tax cuts as well as lower inflation and interest rates, which will be presented as the fruits of their patient hard work.

Will the modest and mixed economic improvements be sufficient by the summer of 2024 to win the election? They hope so but after 13 years of Tory rule, some unforgivable blunders by their predecessors and a national mood for change, the odds remain against Mr Sunak and Mr Hunt being around to take much of whatever credit may be due to them.

Next stop: Boris Johnson’s appearance at the Commons privileges committee to answer questions on Partygate and lying to parliament. For all their talk of a bright technological future, Mr Hunt and Mr Sunak seem unable to escape from their dismal recent past.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments