Grammar schools are a racket that offers the middle classes a public school education for free

Ms May is right to observe that we have quietly but clearly shifted towards a system of selection by good schools based on house prices and, broadly, the incomes of parents. Academic selection could easily make matters worse

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Had we not had an accidental glimpse of a confidential paper being carried into Downing Street the other day, we would certainly not have learned so quickly about the Government's plans to revolutionise the British secondary education system.

While most commentators at the time supposed that the new Education Secretary Justine Greening would attempt a mild expansion of the grammar school system – itself a bold enough step and a marked break with the recent past – in fact she has now been forced to tell the House of Commons that ministers are contemplating a much more general use of academic selection in schools, far beyond what anyone had previously thought. Until recently, one of the more remarkable features of the Tory-led coalition government and David Cameron’s subsequent administration was the apparent reluctance to reverse the New Labour ban on selection and on new grammar schools. Now, with a well-sourced leak from No 10 and Ms Greening’s open admissions to Parliament, we know what is afoot.

It is mostly something to be feared. The lesson of the last few years is that school standards can be raised without introducing selection and without altering the struts of the education system (yet again). As ministers from David Blunkett and David Miliband to Michael Gove and Nicky Morgan acknowledged, selection would not, in practice, raise standards or, crucially, equality of opportunity; far better was to ensure the best use of scarce resources (notably, where possible, devoting more resources to early-years learning) and to have the means in place, such as the pupil premium, streaming, league tables, inspection and rigorous examination and professional regulation, to ensure a sustained improvement in the standard of teaching.

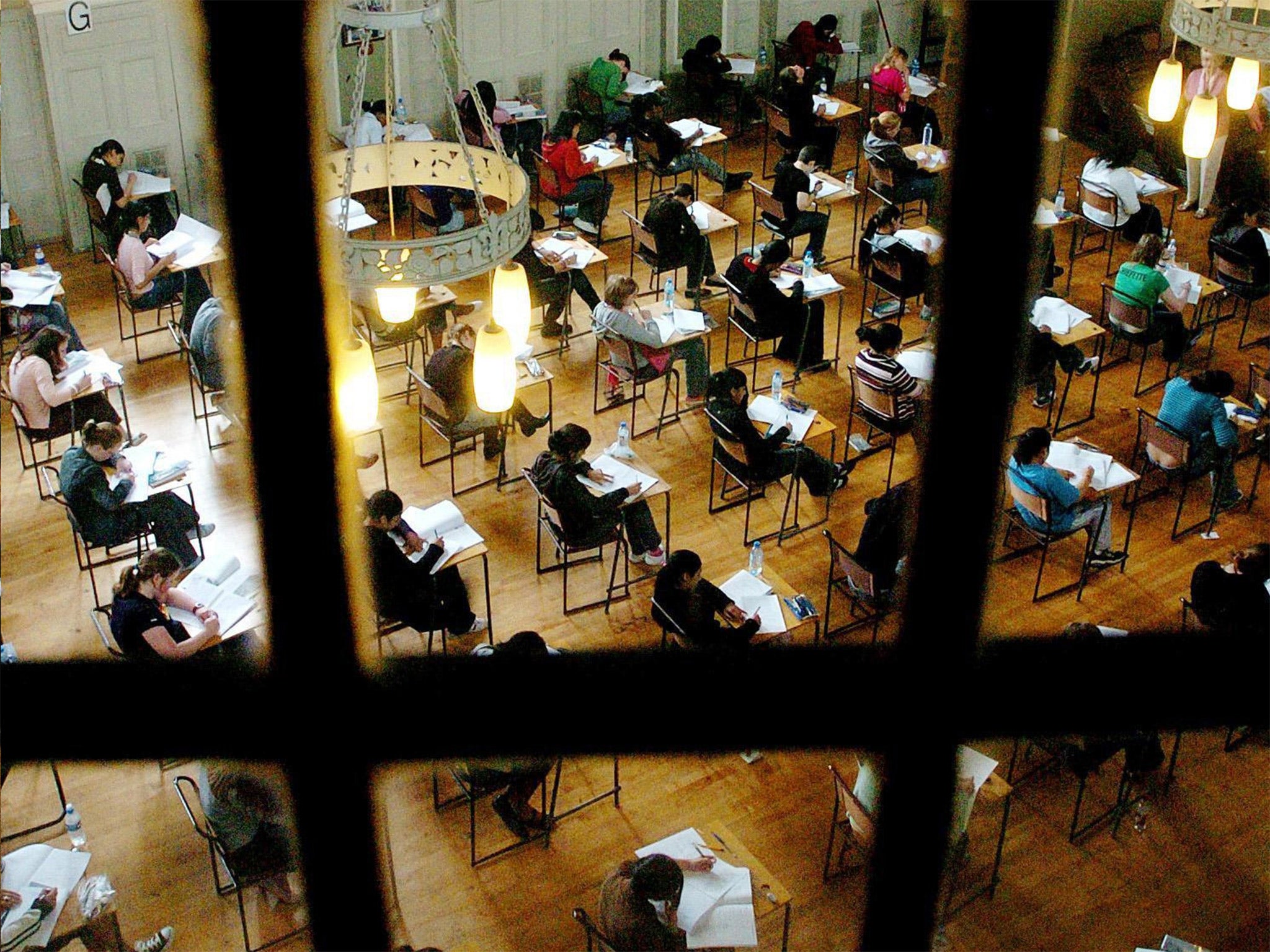

We now have far more variety in the educational ‘eco system’ than we have ever seen before – academies, free schools, high schools (the former secondary moderns), surviving grammar schools, specialist schools, and of course the public schools. It means more choice for parents, and more competition, both between schools and between different models. That is why we see the flaws in the case for grammar schools so clearly – they do not always balance high academic standards and enhanced equality of opportunity. To be blunt, they all too often function as they always have, to offer the middle classes a public school education for free, and thus represent something of a middle class racket.

That said, if we are to have more grammar schools then Ms May’s determination that they be placed in the most deprived areas in the country is a sound instinct, for it is those areas which precisely need these centres of excellence. The worry is that, as Ms May recognises, they attract an influx of the affluent seeking places, which pushes property prices up and, once again, substitutes academic selection for the principle of “whoever pays, wins”.

Ms May is right, then, to observe that we have quietly but clearly shifted towards a system of selection by good schools based on house prices and, broadly, the incomes of parents. The disappearance of affordable social hosing has exacerbated this trend. Academic selection could easily make matters worse, and is one reason why the former head of Ofsted has dismissed the notion of grammar schools as engines of social opportunity as “tosh”. Divisive tosh, too, it should be said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments