So inured is the population to what might be termed the permacrisis in the NHS that the stark reality of what is taking place in our hospitals and clinics is being occluded. Where once a single ambulance taking hours to arrive for someone with a serious, albeit non-life-threatening, injury would be the stuff of headlines, today a wait of many hours at home followed by hours more in A&E feels almost normal.

So poor has the service been, and for so long – and so acquainted are we with absurdly long waiting times – that this dire state of affairs no longer alarms us. The strikes by the ambulance drivers and the nurses, who have deliberately stopped short of refusing to treat “life and limb” emergencies, seem scarcely to have made matters worse.

The NHS crisis may still be topping the news agenda, but the debates are political and about money. The nurses are upping their action, while ambulance crews are postponing theirs, but the troubles drag on – and with no end in sight.

Meanwhile, the country, in its weariness, seems to have forgotten what the human cost of this near-collapse in healthcare means. The Independent now reports and quantifies the misery that is taking place. Bluntly, it amounts to 15,000 deaths since April, with perhaps 500 dying every week because of the long waits in emergency departments – lives that would otherwise have been saved. Had the pandemic and its aftermath, alongside widespread staff shortages, not overwhelmed NHS trusts, the number of deaths would have been far lower.

Despite the resignation of many to an increasingly patchy service, experts in the field insist that there is nothing inevitable about it. They say the health service could be restored to good health without dismantling it or inflicting further futile top-down structural reforms – either of which would merely make matters worse for all. With political will, adequate funding, and a supply of labour and skills from suitable sources abroad, it is perfectly feasible now to restore the NHS to fitness.

It was done before, after Labour returned to power in 1997 – and it requires a real political will along with a popular mandate in a general election. The industrial action by the Royal College of Nursing and Unison will serve people well, as it is adding to the pressure on the government to pay wages commensurate with the proper staffing of the service.

It is time for the government to face up to reality. It will probably lose the strike eventually, because the public recognise that the NHS needs to compete with the private sector for staff. Even if the nurses lose, and the government imposes its pay offer, the NHS will continue to lose medical personnel, which will make working conditions even worse for those remaining, leading to even more departures and an even poorer service.

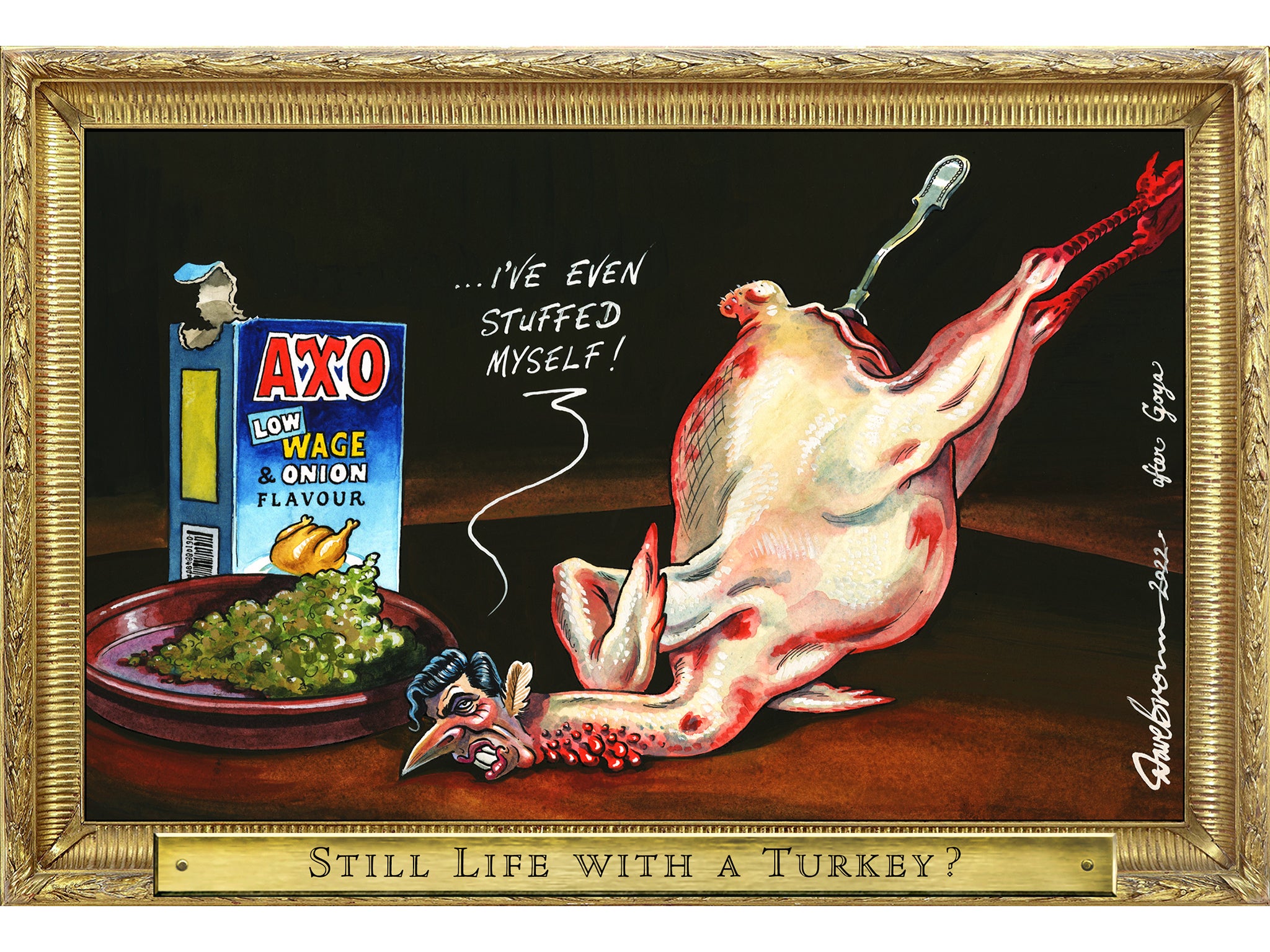

As is often remarked upon, British governments like to keep the NHS on a diet, giving it just enough money to save it from imminent failure but rarely enough to invest in the services it offers and retain its skilled workers, let alone provide for equitable social care.

It’s not a sustainable model, especially given the demographic trends, which have seen people living longer lives but not always in the best of health. The NHS, until very recently, was denied the freedom to produce and implement a long-term plan for training and staffing – perhaps, in recent years, because Brexit and immigration policy rendered it impossible to do so.

The NHS isn’t broken, and it will recover from the current extreme conditions, but Britain does need to have a conversation about what it wants from the health service, and who should pay for it. It can be done, but at the moment the government would rather try to force the nurses and paramedics to surrender. Foolish.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments