The jobs crisis is the biggest economic challenge of our future

Editorial: It would be a tragedy if Rishi Sunak missed the opportunity to build on the success of the furlough scheme

After the 2008 global financial meltdown, predictions of a prolonged unemployment crisis in the UK failed to materialise. In the eyes of economists, workers priced themselves back into jobs, showing the strength of the country’s much trumpeted, flexible labour market.

However, after a decade of austerity and wage restraint, it might be much harder to repeat the process after the severe economic shock delivered by the coronavirus pandemic. After the last crisis, many of the new jobs were in hospitality; that is not going to happen this time.

The latest employment statistics, published yesterday, showed that around 695,000 workers have been removed from company payrolls since March. The claimant count, which includes those in low-paid work as well as the jobless, rose to 2.7 million in August 2020, up 121 per cent since March. Worryingly, the Office for National Statistics confirmed that young people are most at risk; the number of under-25s in work falling by 156,000 between May and July. Although the government has announced a £2bn kickstart scheme to encourage companies to recruit young workers, it may struggle to hit its target to create 300,000 jobs.

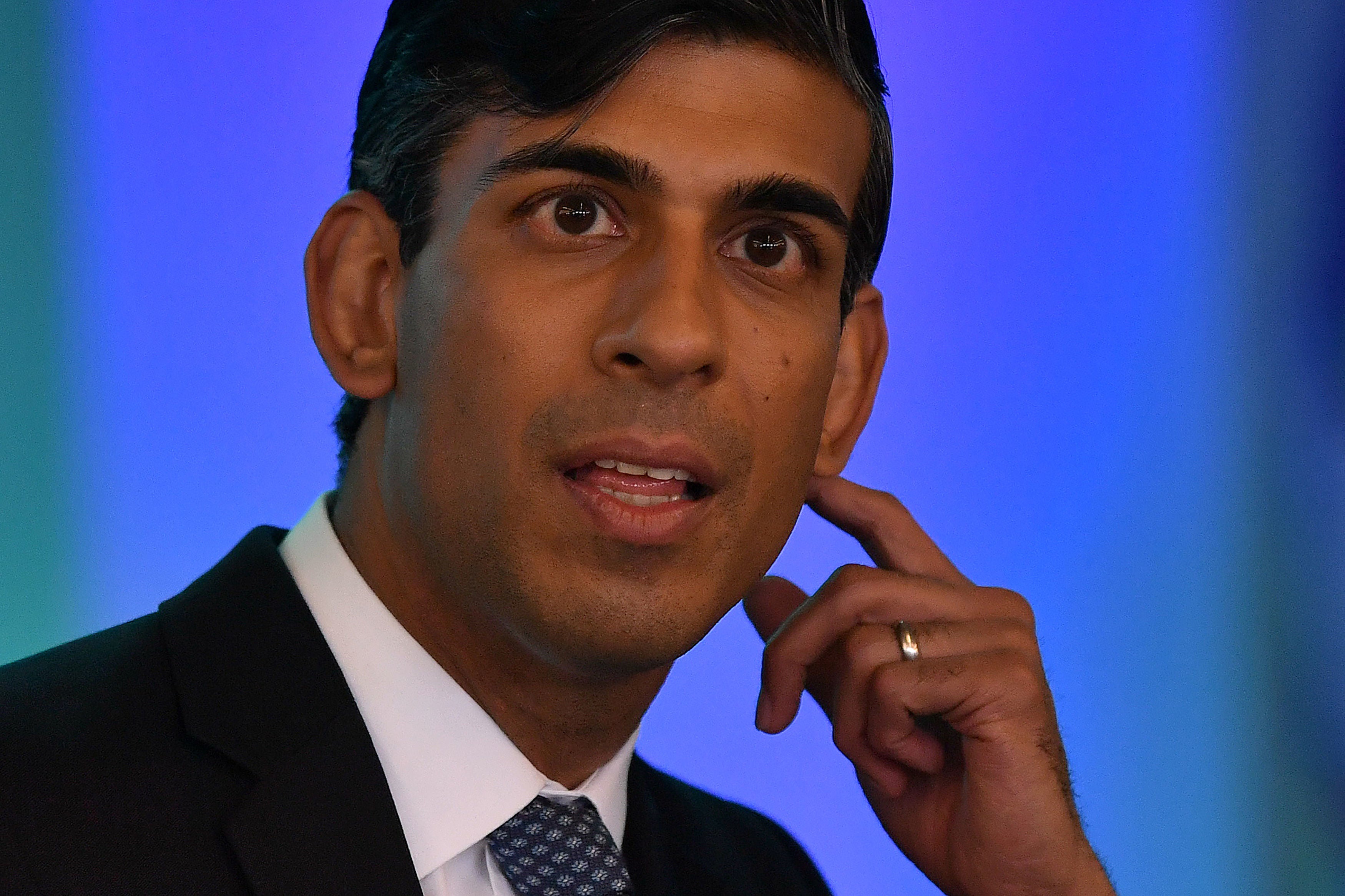

While there has been a welcome uptick in economic activity since the lockdown was eased, that has not yet translated to the labour market. Indeed, things are bound to get much worse before they start to get better. Rishi Sunak’s decision to end his job retention scheme, under which the government funded 80 per cent of the wages of furloughed workers, next month will inevitably trigger a bigger wave of job losses than the sharp rise seen since July. Ominously, some 5.5 million people were still employed but temporarily without work at the end of last month, the majority of them on furlough.

The chancellor is right to acknowledge that some of these jobs are never going to come back. The pandemic will result in some permanent changes – for example, affecting high street stores and hospitality firms operating in city centres. But that does not mean that all of these jobs need to disappear.

The bold furlough scheme, which had cost £37.5bn by the end of last month, has been an undoubted success: some 9.6 million people (30 per cent of the workforce) was covered at its peak. More than half of those furloughed since May returned to work by mid-August. But it would be a tragedy if Mr Sunak missed the opportunity to build on that success. Research by the IPPR think tank revealed that 2 million viable jobs could be lost if he ends the furlough scheme as planned. It wants it to be extended until next spring and reformed to encourage people to return to work part time. Similarly, the CBI proposes subsidies for part-time work; it is better that struggling firms employ two people on half time than make one of them redundant, preventing the loss of skills that hopefully will be needed again soon.

Germany and France have extended their wage subsidy programmes. Mr Sunak should follow suit, even if help is now targeted on the most vulnerable sectors such as hospitality, leisure and the arts. His promise of a £1,000 bonus for firms for each furloughed worker retained until January is unlikely to prove a big enough carrot.

In his speech to the TUC’s annual conference, Sir Keir Starmer was right to call for new targeted support to replace the furlough scheme. He proposed a “genuine national plan to protect jobs, create new ones and invest in skills and training” and offered to work with the government, business and trade unions to agree one.

Boris Johnson should take up the Labour leader’s offer. Business and unions helped the Treasury design the furlough programme at great speed and the country still faces a health and economic emergency.

Sadly, we are not holding our breath for Mr Johnson to do so. His style is the opposite of consensual. As recent events have shown, he is more interested in playing political games, and trying to put Sir Keir on the defensive over Brexit. In doing so, Mr Johnson is looking back at the last war rather than addressing a jobs crisis that is the biggest economic challenge of the future.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments