Even after suspending Jeremy Corbyn, Keir Starmer has a way to go to rebuild trust in Labour

Editorial: The former leader must give a fuller, more detailed account of the decisions he made on antisemitism. But Starmer has to account for serving in his shadow cabinet too

It is sometimes asked why, given the state of the nation, the Labour Party isn’t more popular. While the party leader himself enjoys positive approval ratings, the party is still underperforming, barely ahead of a visibly decaying Conservative administration.

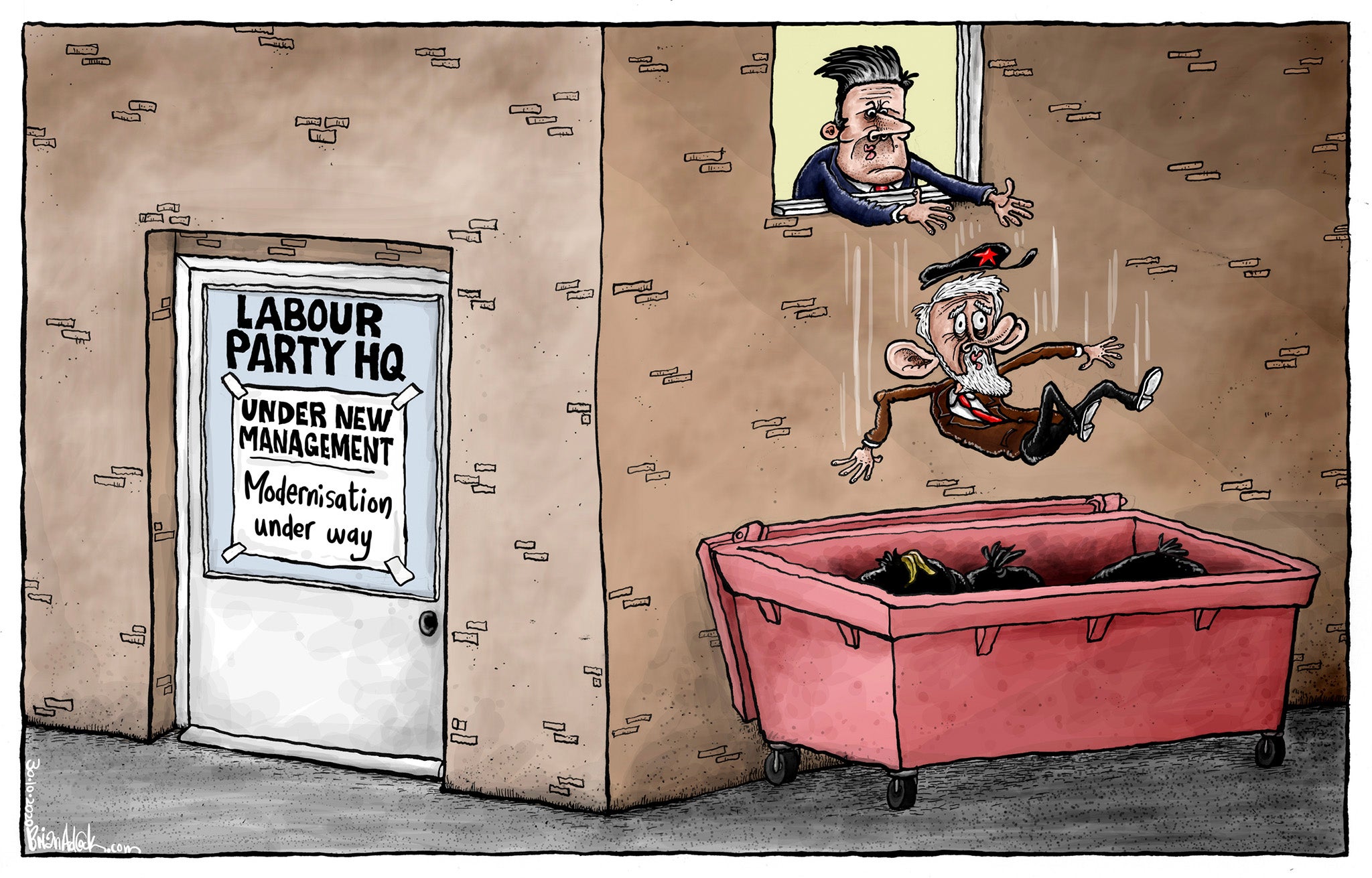

The Equality and Human Rights Commission report into Labour and antisemitism goes a long way to solving that conundrum. Sir Keir Starmer’s move to suspend Jeremy Corbyn was bold, dramatic, and leaves no space for the Conservatives to claim he is hypocritically weak on antisemitism. The kind of leadership Labour needs is on display – but what an appalling mess. Not since 1931 has the party seen fit to treat a former leader in this kind of way, and, it shows the seriousness of the situation and the depths the party reached that it has become necessary. That suspension, and Sir Keir’s unequivocal acceptance of the recommendations, was a textbook example of the swift decisiveness needed to qualify as fit for government. It sends the clearest message possible to the party and the country that there is indeed zero tolerance on antisemitism.

Ironically, though, these dramatic events do tend to confirm the wider public’s suspicion of the party’s innate extremism, at least in the recent past. The Labour Party, in other words, is still suffering from a toxic legacy of the past few years, on antisemitism and much else. The voters may trust Sir Keir, and be increasingly impressed by him, but they harbour deeper doubts about the Labour movement’s instincts, its unity and fitness to govern. That, in turn, is down to the failings of the previous leadership of the party. Sir Keir is seeking to put that firmly in the past.

Mr Corbyn betrayed himself in his own response to the report. He accepted the existence of antisemitism in the party and condemned it, again. Yet, stubborn as ever, he could not help himself; once again he stated that the scale of antisemitism had been “dramatically overstated for political reasons” by opponents inside and outside the party. No doubt there were those who used the antisemitism scandal for their own anti-Labour or anti-Corbyn ends – but that does not exaggerate the actual, disgusting, truth.

Mr Corbyn complains that an opinion poll last year suggested the public thought a third of the Labour Party was under suspicion of being antisemitic, whereas only 0.3 per cent of members actually had a case against them. It was a typically inept piece of spin. The social media chatter on Israel that shaded into antisemitism throughout his leadership like a virus was widespread, and little of it made it into the formal (inadequate) party complaints process. Some of it was promulgated by Labour supporters rather than members – but still part of the cultural problem. The public perception of a party that had lost its moral compass on antisemitism was real and damaging. Merely dismissing it as factionalism or minimising it, helped push Labour to its historic poor result at the last general election. Mr Corbyn still seems to have little understanding of that.

Even if Mr Corbyn is being dealt with in disciplinary terms, pending investigation, and many believe he is not an antisemite, these scandals, some involving his own leader’s office, took place on his watch. Mr Corbyn, in his own defence, must give a fuller, more detailed account of the decisions he took in his time at the top. His senior advisers are also morally obliged to give their own side of the story. Mr Corbyn might also explain, in the context of his own beliefs, why he came to apparently endorse an antisemitic mural in the East End of London, why he made a sarcastic remark about “English irony”, and why he had such difficulty accepting the internationally recognised definition and examples of antisemitism. If he did do so it might, at last, suggest he has begun to understand why, in Sir Keir’s implicit words, he has been “part of the problem”.

Unusually, though, for a political party, Labour has a problem with two of its leaders. Sir Keir too has to account for himself. He did serve in Mr Corbyn’s shadow cabinet (as did deputy leader Angela Rayner, Jon Ashworth and others). No doubt Sir Keir did do his best within those structures, but that is the defence Mr Corbyn has grasped at.

Would Labour’s problem with antisemitism have been solved by Sir Keir storming out in the middle of Brexit? Certainly not. The open opposition to the leadership by most Labour MPs including the likes of Hilary Benn and Yvette Cooper, and the defection of some to a new party, made no difference to Mr Corbyn and his allies. Why did Sir Keir stick with it?

Sir Keir’s actions, including dealing with Rebecca Long-Bailey earlier in the year, have gone a long way to restoring the trust Jewish people can repose in his party. Yet the issue of conscience remains for Sir Keir, and it is a poignant one, for him and for a public that is dismayed about what happened to the people’s party.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments