As Professor Chris Whitty always stresses, all medical interventions are carried out on the basis of weighing the risks. In the case of vaccinations, the estimation of risks and benefits also has to take into account considerations related to the wider community.

Arguably, the four chief medical officers for the UK nations – Prof Whitty for England among them – should have taken into account building herd immunity across the entire population – young and old. While there is now an impressive rate of vaccination among adults, the shortfall among children has left Britain some way behind other western nations.

On this occasion, perhaps because the exercise is purely confined to children, and therefore taking into account the special political and parental sensitivities around them, all decisions have been confined to the welfare of children individually, and as a group. Individually, the risks to children of serious illness from Covid are slight; but the risks derived from lockdowns as they impact parents’ work and schools are much more apparent.

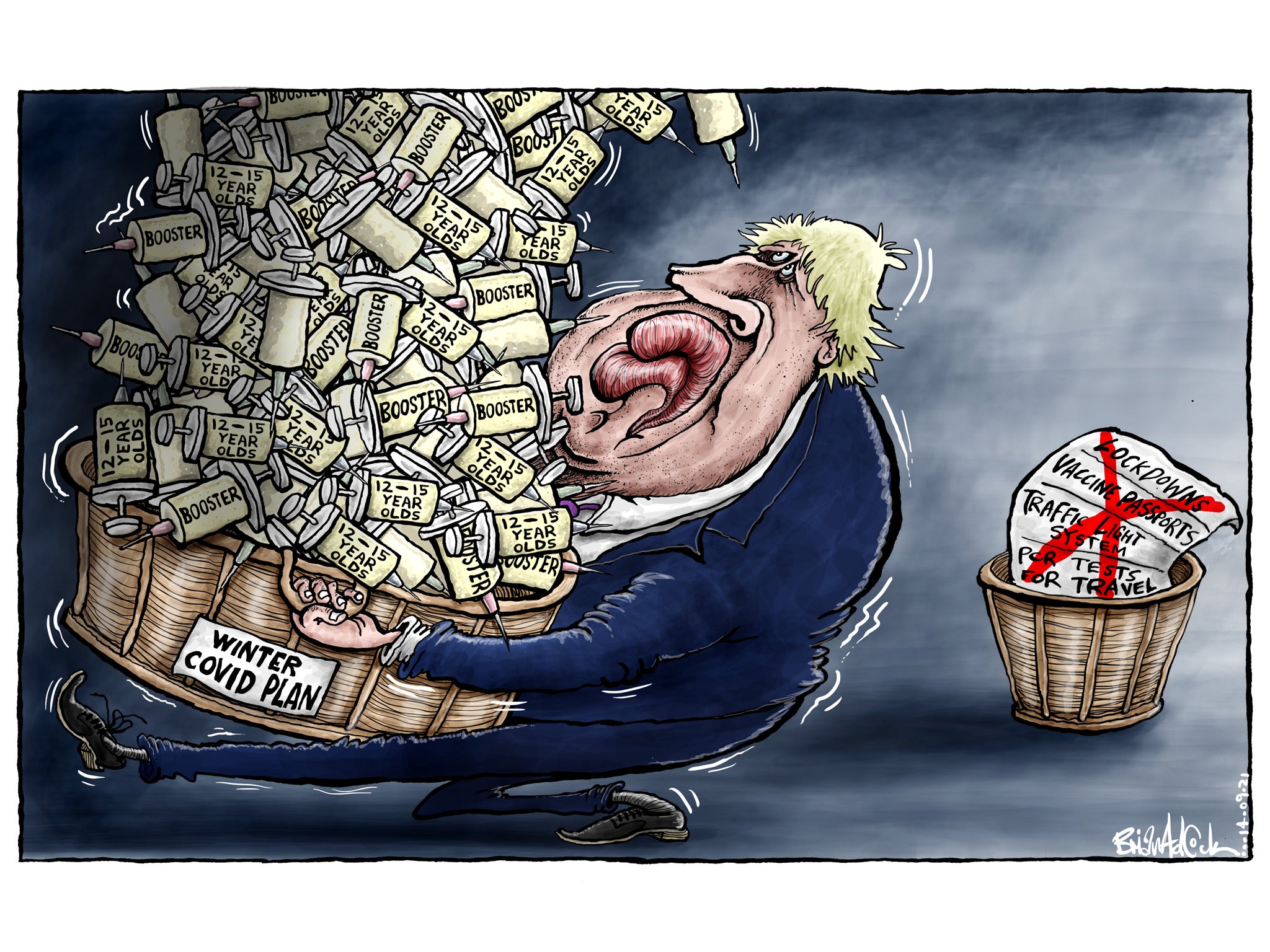

In short, the impact of fresh waves of infections across schools on the education of children – lockdowns, remote learning and general disruption – must be taken into account. Difficult to quantify but very real, such downsides of a largely unvaccinated young population have to be taken into consideration, because the effects on life chances will reverberate down the generations. Narrowly balanced risks and benefits cleaving in various directions have been sifted and an apparently sound conclusion reached: children aged 12 to 15 will now be offered the Covid jab.

There is no sense of compulsion. There is only the universal “offer” of a vaccine to children – it is not compulsory. Children, young people and parents are given the choice, which, whatever the purely medical or scientific arguments, is probably the only reliable way forward, given the high chance of a wide acceptance of vaccination being accepted freely. The precision of the vaccination advice – one dose of one treatment, the Pfizer jab – is indicative of the care taken in making the recommendation to the four governments concerned.

The main criticism of the recent move is that it has come late. Why could it not have been taken and the injections administered before the schools returned? Earlier this year, the UK was in the forefront of the vaccination drive in the west, much to the relief of ministers who were under such severe pressure. The period of deliberation has been necessarily long, but it remains the case that other comparable western nations, such as France, have moved more rapidly, even though their vaccination drives lagged behind for so long.

The challenge now is to win the consent of children, parents and guardians by making sure they are well-informed. The most powerful argument is the advantage to their family life. Families, old and young, have to be able to see and meet one another, and the risks to older or more vulnerable members of any family of serious risk of illness or fatality from Covid are well observed. Lower-income families are less likely to be vaccinated, more likely to be in poorer health and their children are at disproportionate risk from serious and lasting disadvantage from school lockdowns.

It is among these groups, as ever, that general practitioners in particular meet the toughest problems. There should be task forces organised by local public health officials of willing parents, teachers, doctors, social workers and others to make sure that the case, on balance, for their children to be vaccinated is won, and for maximum ease of delivering the jabs, probably in schools themselves. The response among the population as a whole to the vaccine drive suggests that this extension to younger people will be a great success. They need to get on with it, though.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments