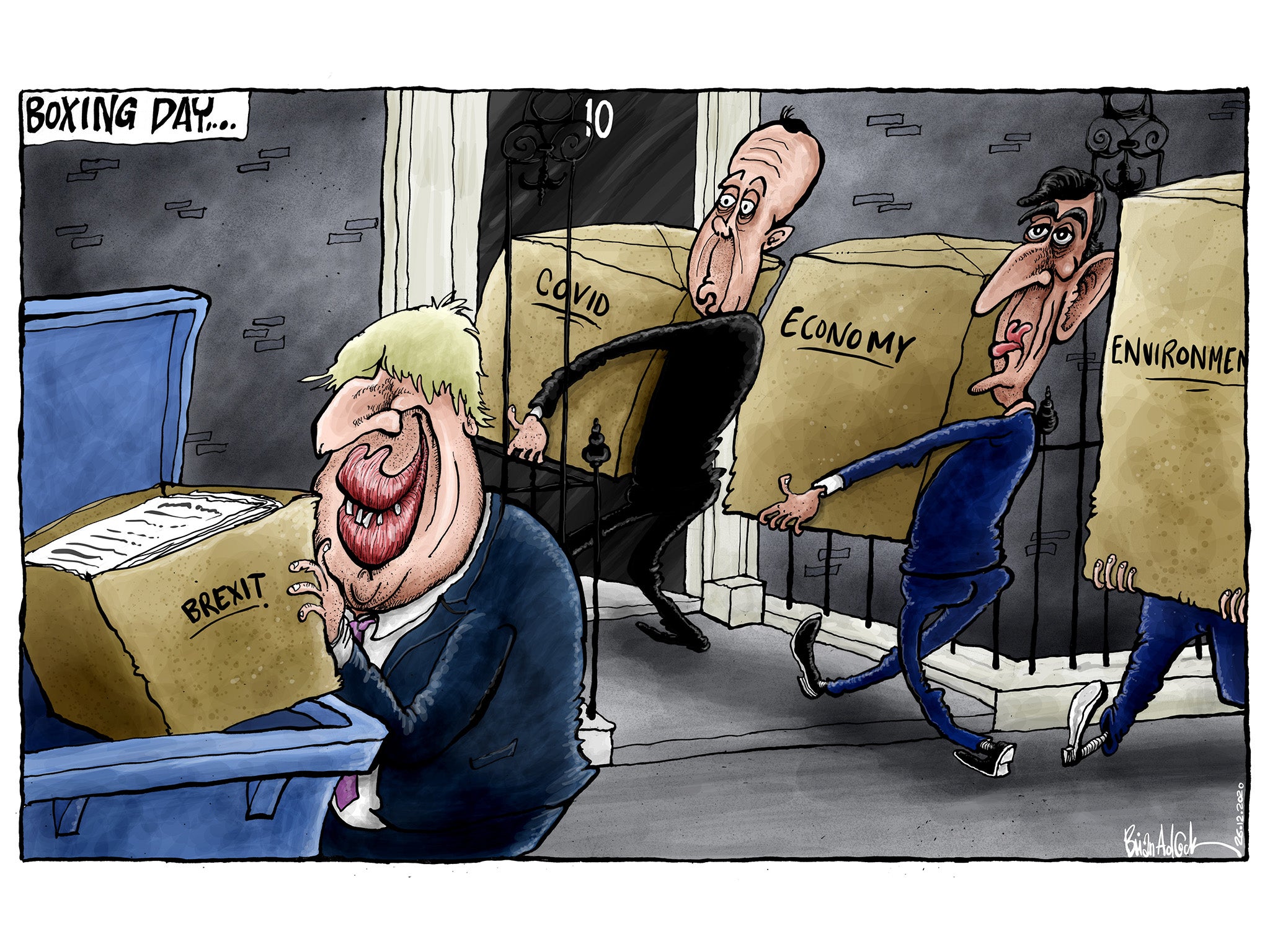

The devil is in the detail when it comes to the Brexit trade deal – the sooner we all know it the better

Editorial: There has, so far, been little talk from the government about how the UK is supposed to make a success of its exit from the EU

Contrary to the Eurosceptic notion of bloated Eurocrats loafing around Brussels even in working hours, Christmas Day saw an extraordinary amount of activity within the EU.

Officials and ambassadors from the 27 member states gathered together to go through the new partnership agreement with the UK. As Michel Barnier, Stephanie Riso and Ursula von der Leyen and the rest of the European Commission team had ensured that the states were thoroughly briefed throughout the process, there were no great surprises. That will make democratic approval across parliaments smoother.

The deal should be done, and there should be no veto; as an exercise in accountability, it is one of the EU’s better moments.

Similarly, the trade deal will pass the House of Commons, with the major dissent coming from the Scottish and Welsh nationalists, plus the Liberal Democrats, who understandably wish to signal their rejection of Brexit once again. Labour, potentially with a few exceptions, will back the deal, sight unseen, on the grounds that the alternative is the ultimate horror of no deal.

Some Eurosceptics may defy the Conservative whip through a devout certainty that no deal is in fact the superior deal. More will mimic Boris Johnson and welcome the free trade partnership as the Christmas gift the prime minister said it was.

It is, though, worth remembering that the British people are not being asked to approve this trade deal, nor were they asked about the withdrawal agreement that preceded it. It seems obvious that the logical and democratically sound thing to do would be – or would have been, strictly speaking – to set these arrangements against the UK’s existing terms of EU membership, and to decide which is better for the country.

It is not obvious that the new arrangements will make Britain richer, safer or happier, and certainly not to the sizeable part of the electorate who would rejoin the EU at the earliest opportunity.

For now, there has been little detail from the government about how Britain is supposed to make a success of all this. Even basic information for manufacturers and farmers on new customs procedures remains sketchy. Those in the service sector face even less clarity about how they might win business in the EU. All they understand is that things will change radically on 1 January and many new barriers to trade and free movement will be erected. Orders will be lost, and with them jobs, incomes and tax revenues.

For the time being, the much-vaunted opportunities presented by Brexit are elusive, and ministers have little idea as to what to do with their new-found freedoms.

Britain’s foreign policy was based for decades on a Venn diagram that placed Britain at the centre of the overlapping circles of the US “special relationship”, the Commonwealth and the European Union. There were other special relationships too, such as with Japan as a friendly centre for inward investment, and with a number of other nations because of a world-class commitment to international aid.

That has now been shattered, with nothing to replace it except appeals to sentiment and history, and an inflated defence budget. Britain is no longer the bridge between different international communities, leveraging its modest status and “punching above its weight”, as the diplomats used to say. In a dangerous world, the EU is what President Von der Leyen calls it: one of the giants. Britain is diminished.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

25Comments