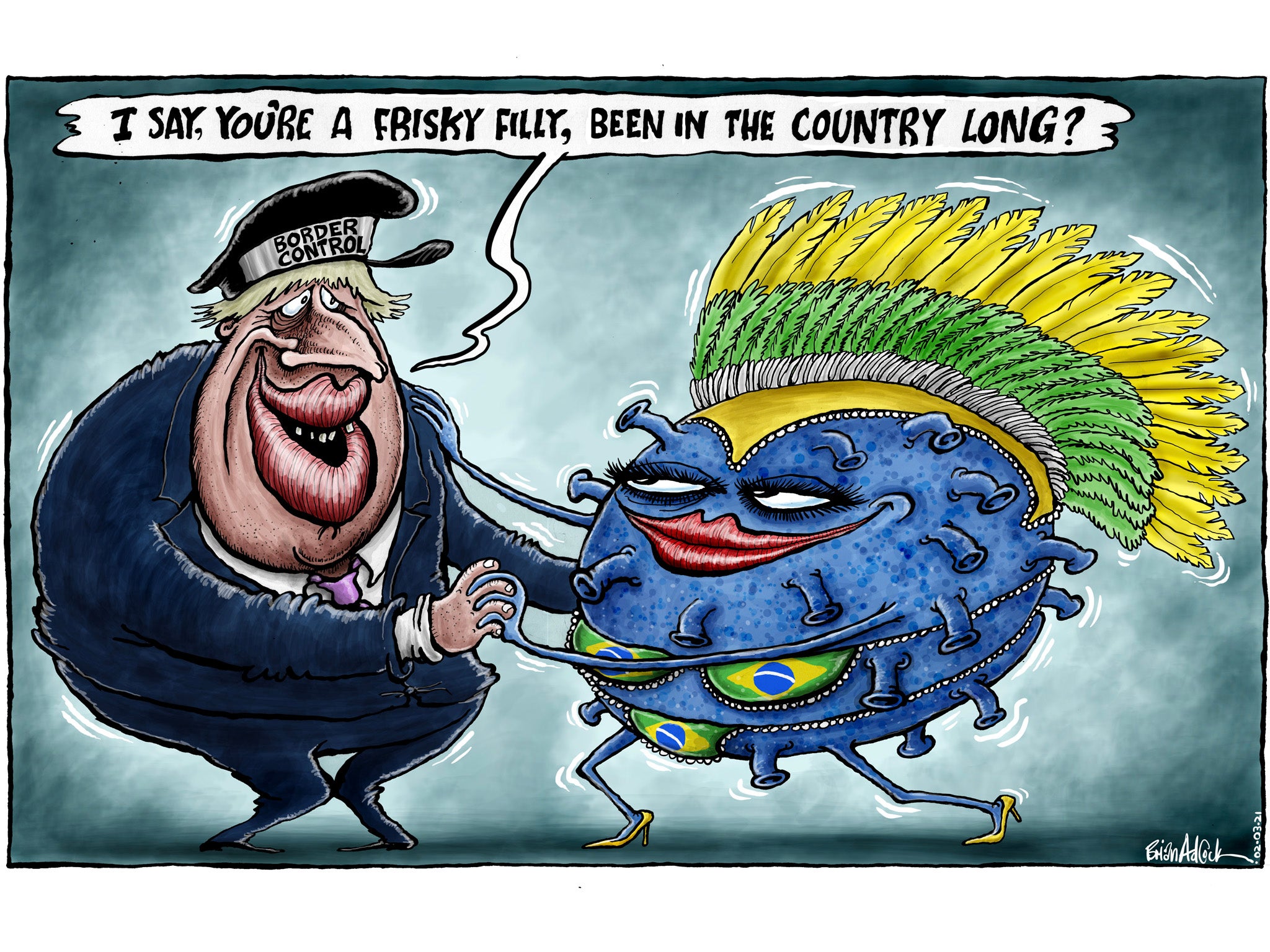

The hunt for the missing Brazilian variant patient says a lot about the government’s Covid response

Editorial: Most poignantly, hotel quarantine was brought in too late to stop this incident from potentially damaging the UK’s ability to control the virus

The frantic search for a missing unnamed carrier of a coronavirus “variant of concern” tells us three things about the government’s response to the pandemic.

First, and most poignantly, the government dithered for too long before it imposed the hotel quarantine regime. The potential spreader came to the UK a matter of days before the border controls were tightened up. Hotel quarantine was brought in on 15 February, but the person was clearly in the country before that date, because they applied for a Covid test in the UK just before then, and the result was positive.

The UK’s superlative ability to chart the genome sequence of virus samples means that this case has been identified as one of the Brazilian variants, P1. That means it is more transmissible than the original virus, and it may be more resistant to antibodies. That, in turn, suggests that the vaccines may be less effective against it, and that those who’ve already survived Covid-19 could be reinfected. As a result, the lockdown roadmap could conceivably be disrupted by a rapid spread of a more troublesome mutation.

So there is a great deal at risk. The dithering about the policy on border quarantine has been demonstrably damaging to the control of the virus and its variants, and ministers have to take collective responsibility for it. The home secretary, Priti Patel, has made it known that she has long favoured a more restrictive policy, but was overruled. For once, she was right, but she must still take her share of the blame for what has happened, and is yet to happen as a result of this blunder.

The case also reminds us that Britain’s test and trace system still leaves much to be desired. The carrier was conscientious enough to take a test for Covid on 12 or 13 February. However, the paperwork wasn’t filled in properly, and he or she is now impossible to contact. The government has had to fall back on a public appeal, which is hardly ideal. The Royal Mail has an excellent system for tracking the post, and this could easily be used for the dispatch and return of Covid tests. The procedures at testing centres could also be tightened up, to help minimise administrative errors. There is more that can be done, and it is never too late to improve the system, given the inevitable emergence of new, more deadly, variants.

A third lesson is that vaccination is not a panacea. Some of the more optimistic springtime coverage of the successful vaccination programme and the roadmap may have given the misleading impression that the end of the pandemic is at hand, and the shortcomings in other policies to control the virus – testing and quarantine for example – are becoming irrelevant. That is wrong. The resulting complacency means more lives and livelihoods will be lost as a result.

By now, this particular Brazilian variant will already have reproduced, and will no doubt be picked up by more testing in the coming weeks, and how widespread and how resistant to antibodies it is will be discovered. A new vaccine to deal with it can be quickly delivered, in a matter of months, but that would still mean easing lockdown will take much longer. Boris Johnson’s promise of an “irreversible” end to lockdown may itself have to be reversed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks