Boris Johnson and Sajid Javid need to be clearer about what ‘living with the virus’ actually means

Editorial: The government has thrown all the levers of policy into reverse before Monday’s ‘irreversible’ opening up

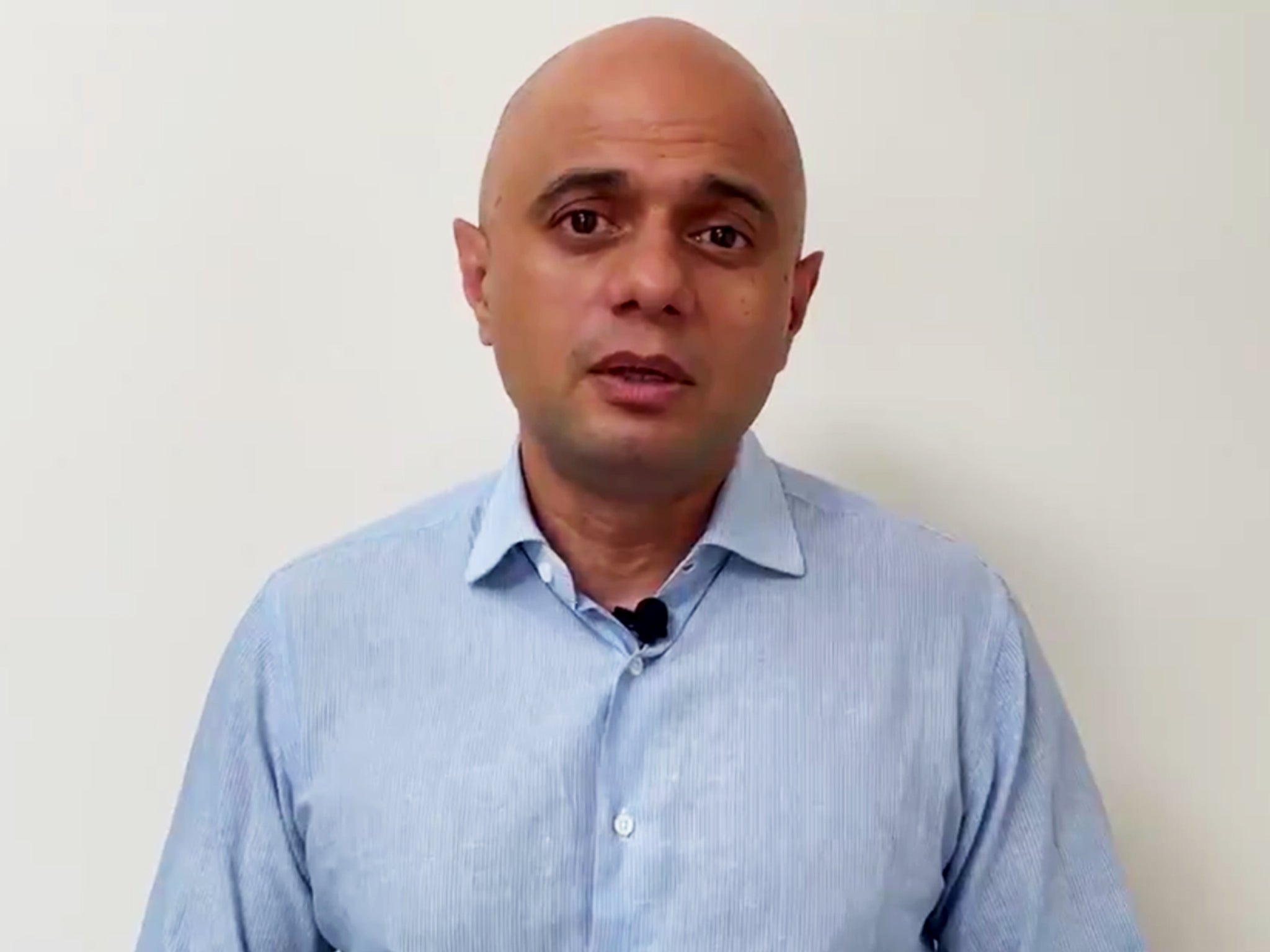

Sajid Javid is just one person, and policy should not be made by anecdote, but there is something telling about the health secretary contracting Covid two days before his government lifts most of the remaining legal restrictions.

The first is that it underlines the problem of vast numbers of people isolating themselves, as he is now required to do. He can carry on doing most of his work remotely, but there are hundreds of thousands of workers who cannot, and the economy – only just beginning to emerge from the lockdown – is beginning to feel the strain.

It may be that this is necessary, as Mr Javid’s case also reminds us that two vaccinations offer incomplete protection against catching (and passing on) the virus. He appears to confirm that a double vaccination protects against serious illness – he said his symptoms are mild – but if the aim of policy is to curb the spread of the virus then it would seem that isolation for double-vaccinated people should continue.

Above all, the health secretary’s condition is bound to alarm further a nation that was already nervous about Monday’s easing of restrictions. A Savanta ComRes opinion poll for The Independent found that 54 per cent of people said that step 4 of the roadmap out of lockdown should have been delayed beyond 19 July, with only 33 per cent saying it should go ahead.

As it is, it seems that the government has thrown all the levers into reverse since Mr Javid took office just three weeks ago, declaring blithely that his task was to open up the economy. Instead of lifting the restrictions on Monday, most of them will become voluntary rather than compulsory – or, if compulsory, the compulsion will come from the transport authorities and shops rather than from central government.

It was always going to be difficult to explain the rationale for easing restrictions at a time when the number of infections was rising sharply. Professor Chris Whitty, the chief medical officer, warned the prime minister and the nation about it. He and Sir Patrick Vallance, the chief scientific adviser, have gone along with dropping most legal restrictions, but the prime minister did not appear to be listening to the subtext of what they were saying, which is that public opinion would need to be prepared for taking what was likely to look – by the time we got to 19 July – like a rash decision.

Instead, Boris Johnson has given the impression of being taken by surprise, and of scrambling to keep up, once again, with a virus that refuses to succumb to his optimistic bluster. The only sense in which the path towards normality has been “irreversible” is that most of the changes have been reversed before they have been made. The latest example is the decision to continue to require quarantine for travellers returning from France, after thousands of people had made plans having been told that the requirement would be dropped.

Of course, the pandemic keeps changing and governments need to respond quickly to new information, but ministers have been unclear about what the new information about France is, and they knew that infections in the UK were rising fast towards 100,000 a day. It should have been obvious that this was going to cause huge problems for travel and the rest of the economy.

Keir Starmer, the leader of the opposition, pointed it out in the House of Commons. Yet the prime minister, in his speech on Thursday, devoted only a few sentences at the start to the “difficult days and weeks ahead”, insisting that “it is highly probable” – only highly probable – “that the worst of the pandemic is now behind us”.

We hope that Mr Javid gets well soon, but it is time for him and Mr Johnson to be straighter with the British public about what “living with the virus” actually means.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments