The Tories are in trouble, and Boris Johnson isn’t their only problem

Editorial: As with other political leaders in jeopardy in the past, one of Mr Johnson’s few strengths is that his enemies are divided, and no clear replacement figure is being suggested

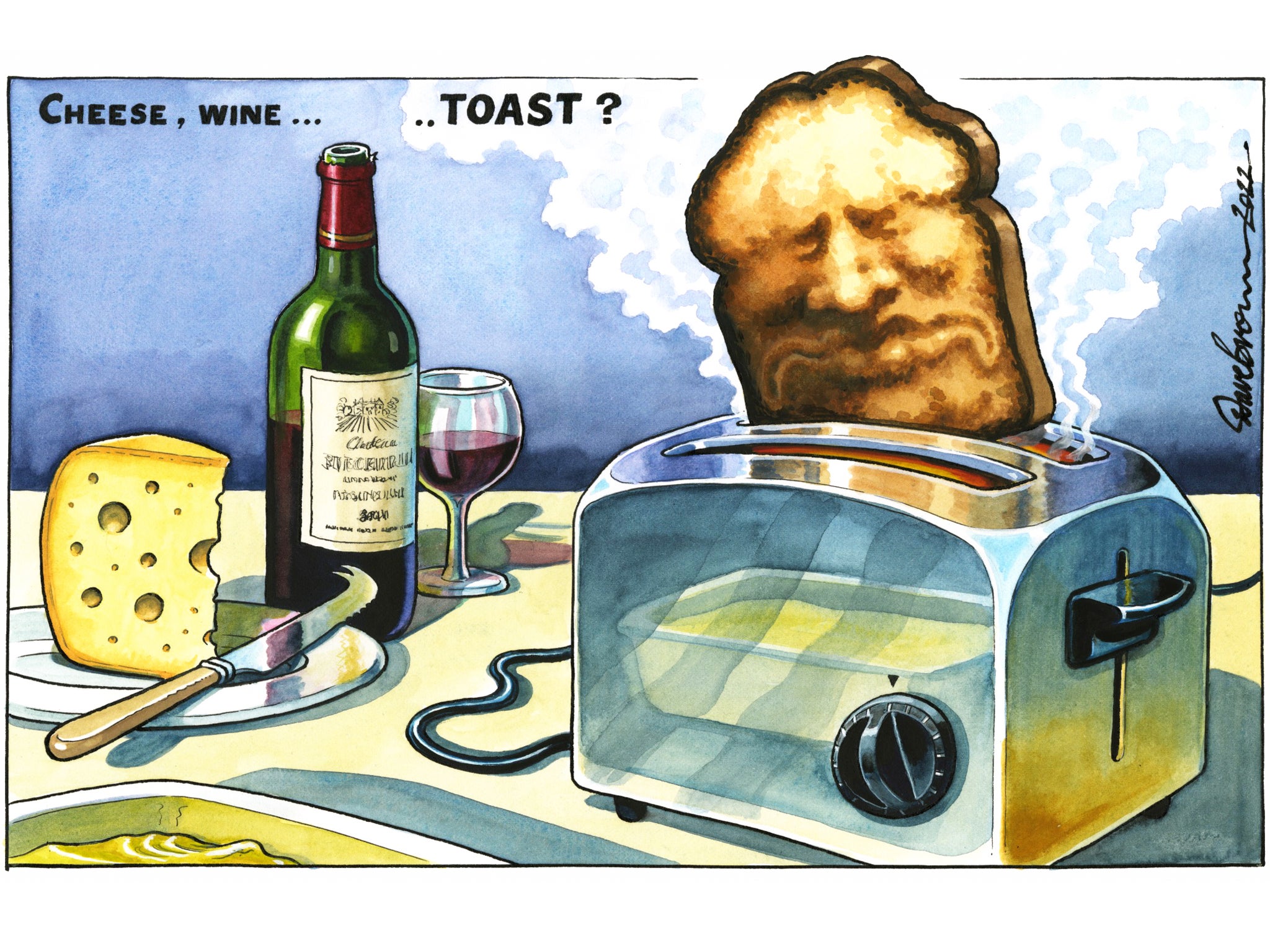

Two of the more unconventional but useful indices of political trouble are the extent to which a leader becomes a figure of fun rather than mere scorn; and when (in smaller countries) their travails attract the attention of the foreign press.

Measured on those yardsticks, Boris Johnson cannot count on seeing another new year in office. In the Commons, he stated that when he entered the garden of Downing Street on 20 May 2020 to see groups of people enjoying the nice weather, drinking booze and enjoying party food, he assumed it was a “work meeting”. The leader of the opposition, Sir Keir Starmer, made the most of a prime minister, known as something of a bon viveur, not recognising a good time when he sees it.

Mr Johnson, some time ago, used to be funny in the right sorts of ways; now the clowning is a source of a different kind of embarrassment. The reveries have not enhanced his moral authority or any impression that he is a serious leader for serious times. Now he is self-isolating after close contact with someone who has tested positive for Covid, but many angry families feel he has been isolating himself from their suffering for far too long.

The bemusement has also gone global. The New Yorker, for example, carries an article about how Downing Street was transformed by the prime minister into a latter-day speakeasy during lockdown: “The prime minister is embroiled in a scandal involving government staffers allegedly yukking it up while imposing strict measures in the UK.” (“Yukking” being American for hearty laughter, apparently.)

No one need be fooled by the formulaic declarations of unwavering loyalty from (most) of the cabinet. Sincerity is cheap at the top of politics, and the more striking feature of the rally-round was, first, that it needed doing anyway, and second, how sluggish and grudging some of it was.

Rishi Sunak’s tweet that he was in Ilfracombe was far from innocent, and his much later pledge of allegiance was curt. The chancellor may as well have published his leadership campaign slogan instead. The most sincerely outspoken of the prime minister’s supporters were those that have the most to lose from regime change (ie the sack), including the home secretary, Priti Patel, and the leader of the House of Commons, Jacob Rees-Mogg.

Mr Rees-Mogg dismissed the leader of the Scottish Conservatives, Douglas Ross, as a “lightweight”, for the crime of calling for Mr Johnson to quit, which is only what a large number of his colleagues are unwilling to say in public. There are other, ominous, silences from the hard-line Brexiteers.

Mr Johnson is not bereft of friends and allies, but they’re not exactly forming a praetorian guard around him. Most of his backbenchers seem reluctantly willing to wait until the report by Sue Gray, a civil servant, into partygate, or offer him another six months’ probation. This is not a firm foundation for a leader to pilot his party or the country through the 2020s and “build back better”. There is a strong whiff of decay about, but it was there before partygate.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

The prime minister has been in and out of trouble ever since the Dominic Cummings scandal in the summer of 2020, and his standing and that of his party have been hammered by the cost-of-living crisis, multiple sleaze scandals, the refugee crisis and some excruciating incidents such as the “Peppa Pig speech” to business leaders. The government’s internal critics are alarmed, variously, by the general sense of drift, Brexit (fishing and Northern Ireland), plan B, the tax hikes and the net zero green agenda.

More than anything, though, the Conservative Party is spooked by the revival of the opposition parties. The loss of the Amersham and North Shropshire by-elections to the Liberal Democrats, a 10 per cent swing to Labour in Bexley, and a 10-point deficit in the opinion polls (even before Mr Johnson’s unsatisfactory statement) tell Tory councillors, MPs and ministers all they need to know about their future prospects under Mr Johnson.

As with other political leaders in jeopardy in the past, one of Mr Johnson’s few strengths is that his enemies are divided, and no clear replacement figure is being suggested. Unlike when Theresa May was defenestrated in 2019 by Mr Johnson and his allies, this time there is no frontrunner, and the Tories are faced with a very messy and possibly counterproductive leadership challenge, with no subsequent election.

They could, quite conceivably, end up with a leader with most of Mr Johnson’s flaws but none of his vestigial talents as a campaigner. Mr Johnson may be one of their greatest liabilities, but he is not the only one.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments