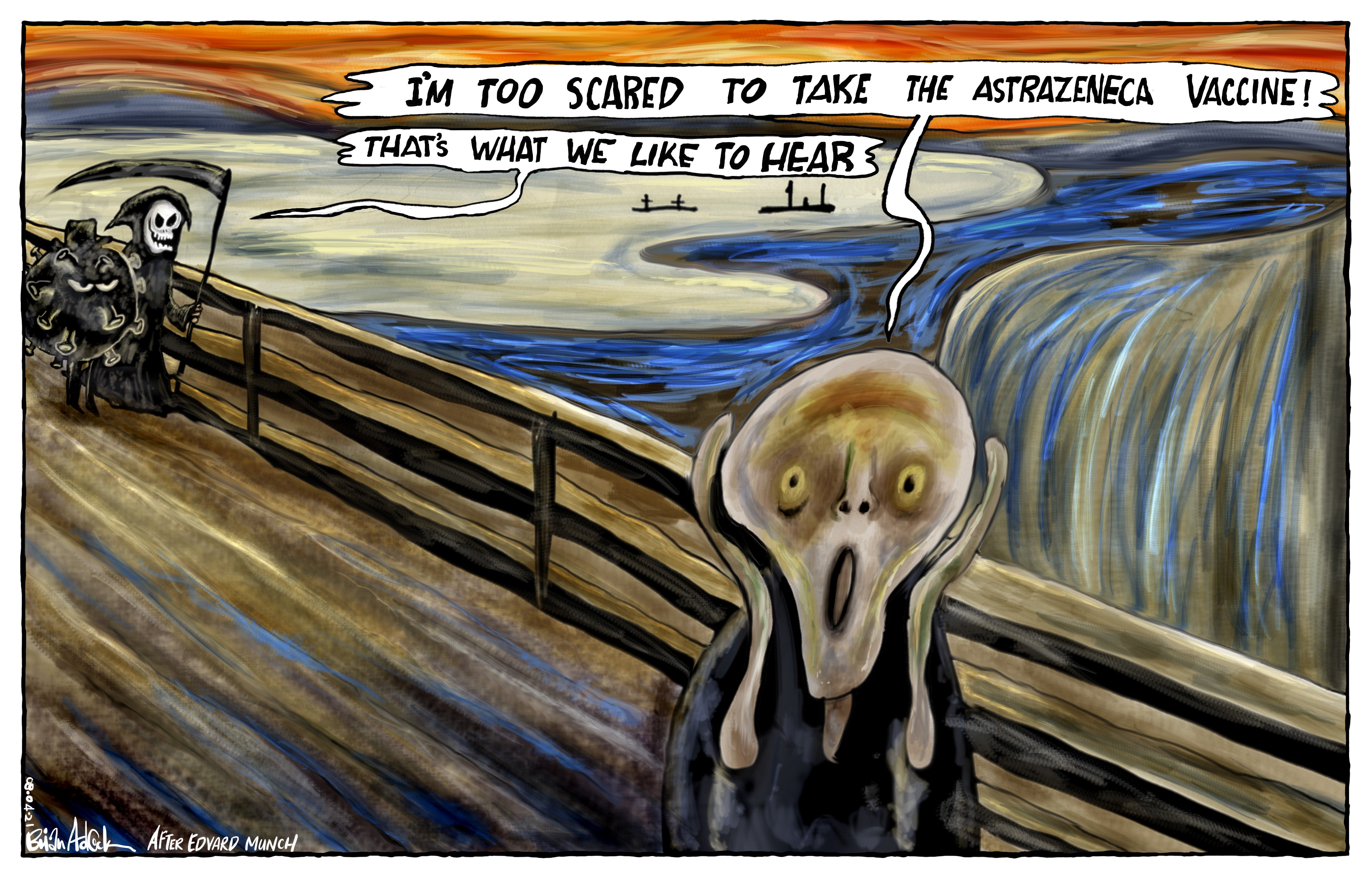

Fear of blood clots must not undermine the case for vaccinations

Editorial: The possibility of getting fatal blood clots from Covid are vastly higher than from the Oxford-AstraZeneca jab. We must avoid a catastrophic third wave, economic recession, and help build herd immunity

So, there seems to be a link after all. The European Medicines Agency says that blood clots are a “very rare side effect” of taking the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, and should be listed a such. The British authorities are a little more cautious, rating such side effects as a “strong possibility”. Neither side wants a ban, or even a pause, but some caution on exposing the young to such risks, given that Covid-19 is far less harmful to their immediate personal health than to older people.

The figures quoted are of handfuls of people among many millions who have taken the vaccine. The vaccine is still safe, but among the young, the under-30s, the balance of advantage is less overwhelming than among their older counterparts. In any case, alternative vaccines are and will be available in Britain, from Moderna and Pfizer. The big picture is unchanged – that the possibility of getting fatal blood clots from coronavirus is vastly higher than from the AstraZeneca vaccine, with only the possible exception of the very young. The authorities have acted with due caution, but decisively and placed the public’s health first. It has been an exercise in open and transparent public health management. The worry is that the controversy, a recent history of panicky news stories, and the change in policy on the AstraZeneca vaccine for the under-30s will undermine the case for vaccination more widely.

On one reading, the damage, such as it is, would apply to the AstraZeneca product only, because there appears to be a clear difference with the other commonly used alternatives. The general suspicion now falling on among some towards vaccines, in general, might then alight on only one of the available vaccines – the AstraZeneca vaccine as a sort of lightning conductor. The effect may be to make the Pfizer, Moderna and other doses seem “safer”, subjectively.

The alternative outcome, and a grim one, is that the younger cohorts simply say no to the offer of any vaccine. They already know that the risk of death or serious illness befalling them from coronavirus is vanishingly small. Personally, with such little perception of risk to their person, there may seem to them to be a rational case for avoiding the vaccines, though they underestimate the damage that even a “mild” case of the disease can inflict on a healthy young person or, moreover, the lingering life-changing legacy of long Covid. Appeals to help bolster herd immunity and the health of the community as a whole might not prove particularly effective. In which case periodic outbreaks of the virus, lockdowns and economic recession will be that much more commonplace in future (with all that implies for the life chances and prosperity of the young).

Read more:

The weeks ahead will show whether those in their thirties and forties are willing to take the AstraZeneca vaccine, or indeed any vaccine. If they prove too hesitant then consideration must be given to widening the choice of vaccines available to them – even though it might introduce some extra delay. For many used to consumer choice, it seems odd not to be able to choose which vaccine to have, just as you might favour one brand of lager or smartphone over another. The vaccine is, after all, a rather more vital matter, though the costs and complications of storage would make vaccine choice more tricky to administer. In the interests of reaching herd immunity and avoiding a catastrophic third wave of coronavirus, though, the NHS might have no alternative but to change its usual command-and-control habits.

The question of further incentivising the younger generation through other mechanisms will also arise. Already it is clear that foreign travel will require a vaccine passport, just as now certain destinations demand protection against, say, yellow fever or hepatitis. It will be an unavoidable feature of future holidays, and a powerful reason to get vaccinated. That will certainly keep the overall Covid-19 vaccination rate higher, and the government’s pilot schemes for status certification will also offer some evidence of how other incentives can operate. Remaining within the borders of the UK for the rest of one’s life must test even the most ardent patriot.

The deputy chief medical officer for England, Jonathan Van-Tam, a trusted and conscientious public official calls it a “course correction”, with the UK’s vaccination programme continuing to go “full steam ahead”. Indeed, on this long journey towards safety, as Professor Van-Tam points out, such changes in policy are only to be expected. The pity of it is that they are much less likely to be understood.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments