Biden will have a hard task getting the US to commit to Paris targets

Editorial: Post-Trumpian radicalisation will leave a lasting legacy. The new president faces a battle in laying the foundations for net-zero carbon emissions by 2050

Given how important oil, gas, coal and fracking still are to the American economy, it was brave of Joe Biden to even mention the climate crisis during the election campaign, and his opponent did his best to highlight the potential for job destruction contained in Mr Biden’s climate plan. For Donald Trump, the climate crisis was at best a hoax and at worst a Chinese plot to destroy the US economy.

Still, Mr Biden won, which suggests that the tide of opinion in America is moving towards science and away from denialism. A succession of freakish extreme weather events may be persuading more voters to take the future of the planet seriously. So too is the ever-closing gap between the present and environmental Armageddon. Mr Trump and President Biden will probably not be around to witness the mid-century cataclysm, but many of their fellow citizens of voting age will be.

A citizen born at the time of the original Earth Summit and Rio agreement on the climate crisis in 1992 should now be looking ahead to a comfortable retirement around the 2050 date usually assumed to be crucial to stopping the destruction of life on Earth.

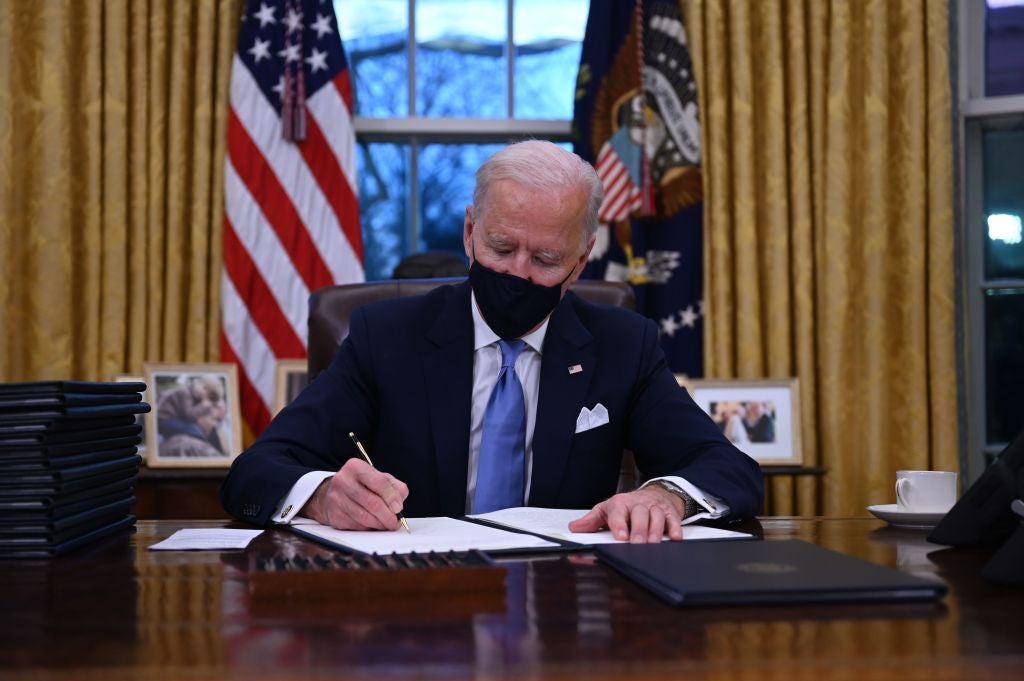

True to his word, Mr Biden has acted. He has signed the executive order taking America – still a major polluter – back into the Paris climate agreement. Mr Biden’s proposal for net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and clean electricity generation by 2035 would fit broadly into the Paris agreement’s obligations.

Mr Biden has done something that seemed impossible even a few years ago, and won a popular mandate for a green evolution. It will cost some $2 trillion (£1.46 trillion), and cause disruption in areas reliant on fossil fuels for their income. It will also create new green industries and new sustainable jobs, but they may not be a perfect match for livelihoods lost. The moral courage that Mr Biden displayed in moving America this far will be needed all the more as he tries to implement his policies.

As his predecessor found, signing an executive order is the easy bit. If President Biden wants Americans to switch to greener cars and to solar and wind energy generation he will need to use regulations, taxes and incentives to do so, and he will have to win the arguments. Every president since Jimmy Carter who has tried to change America’s high energy habits and to take on Big Oil has found it a bruising experience; most do not bother. While modern corporates and consumers freely acknowledge the reality of the climate crisis and the need to act, getting them to commit to zero emissions or ditch the gas-guzzling pickup truck is another matter. Hard-pressed families find they have bigger things to worry about than recycling.

Mr Biden has only slim majorities in Congress to rely on to take legislative action at the federal level, while much environmental rule-making is conducted at state and city level, and not all territories are as pioneeringly green as California. There is an obvious mismatch between the president committing to goals and targets at the international level, but being unable to push through what needs to be done at the national and local level, where vested interests and “pork barrel” politics can disrupt the worthiest of aims. That mirrors the mismatch between the electoral cycle (short) and the environmental one (long, but becoming pressing).

Mr Biden may be lucky to make much progress during his term of office, despite his talent for striking a deal. Twelve years ago, Republican leaders in Congress bluntly told Barack Obama that their job was to make his presidency a failure, and it took all of Vice President Biden’s skills to get Obamacare through against the odds.

Post-Trumpian radicalisation, if it sustains, means that Republicans in DC and across state houses and city halls may be even more belligerent than in Mr Obama’s time, especially if they choose to take their lead from the Great Pretender of Mar-a-Lago. They cannot block the president from rejoining the Paris climate framework, but they can certainly frustrate efforts to make it effective.

Even so, critics in Mr Biden’s own party claim his plan does not go far enough, quickly enough. More radical Democrats want a “green new deal”, with net-zero emissions by 2030. They are right that there would be huge symbolism in the US, as the largest historical emitter of carbon, going above and beyond the line set by the Paris Agreement. A nation that believes in American exceptionalism once again leading the world, this time in its greatest crisis.

Yet the 2050 target is perhaps the best that can be expected from the world’s most developed economies, let alone Brazil or Indonesia, with sweeping changes needed in every sector. After the Trump administration, US involvement in what is still an ambitious target is hugely significant in itself. As President Biden knows better than most, politics is the art of the possible.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments