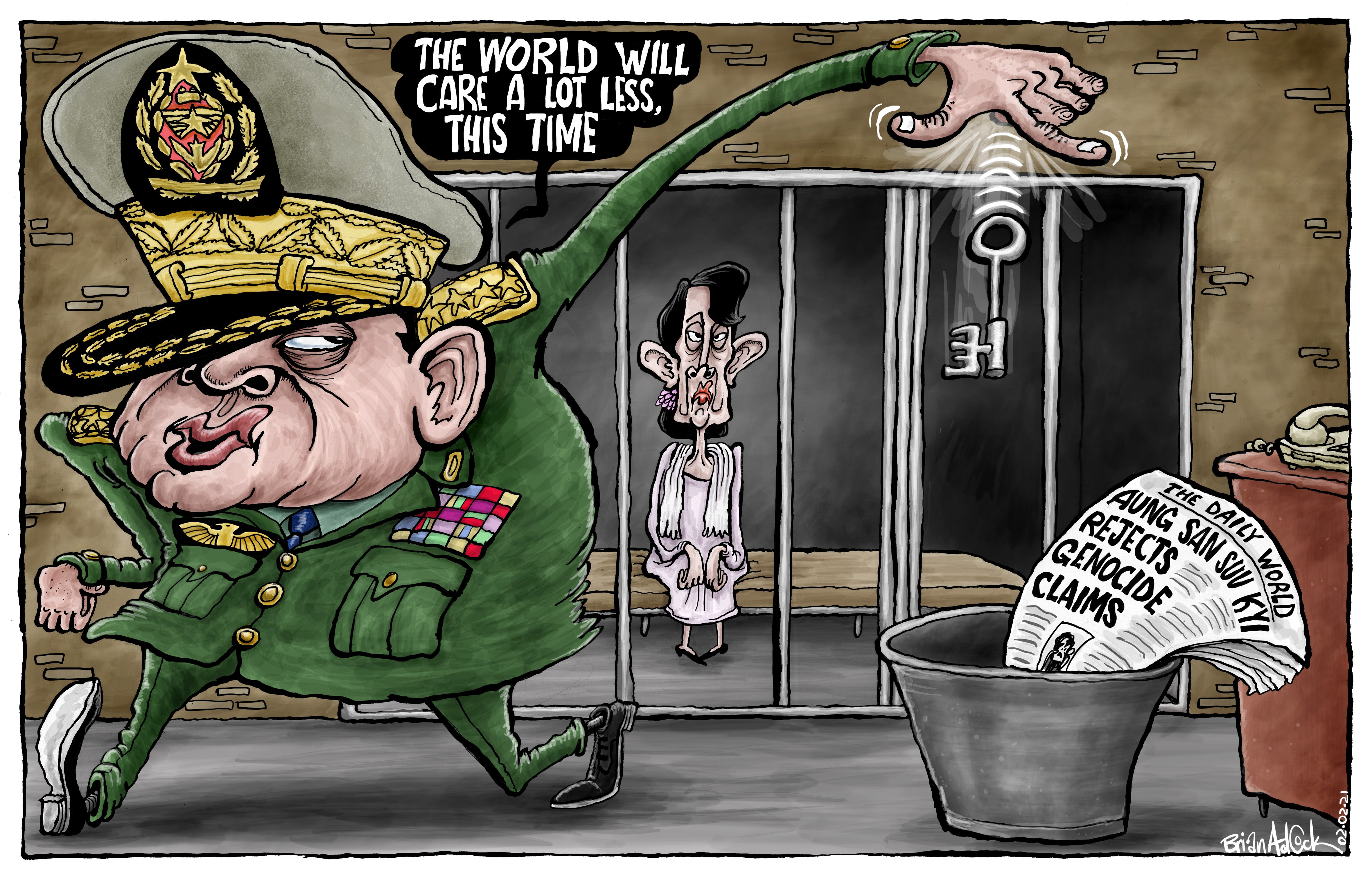

As the old saying goes, those who try to ride a tiger end up inside it. So it is with Aung San Suu Kyi, de facto leader of Myanmar. Once a human rights hero, then an apparently willing collaborator with the army in the persecution of the mostly Muslim Rohingya minority, now Ms Suu Kyi is under arrest.

After years of resistance to dictatorial military regimes, she came to a cosy arrangement with them a few years ago: she would put an acceptable face on what was in essence still a military regime. Now the generals have concluded that they have no further use for her, they have turned on her and gobbled her up. It was easy. They have declared her election victory last year void, and have taken power in a traditional coup d’etat.

Myanmar, after a brief and unhappy experiment with a kind of licensed democracy, has reverted to type, and Ms Suu Kyi presumably finds herself once more under house arrest, as she was for 15 years before her release in 2010 and she went on to win the free elections in 2015. Warily, the army allowed her to become state counsellor and foreign minister, in effect president of the country. Now they have casually deposed her. Perhaps she is under house arrest; perhaps she will even be pushed into exile once again.

Unlike her previous long period in opposition, however, Ms Suu Kyi will now find much less sympathy in the west. In her long years as a lonely advocate of human rights for her nation she was lauded by governments, religious leaders, universities, the UN, and in 1991 was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. President Barack Obama paid a pilgrimage to her. The whole of the liberal world wanted a selfie with “The Lady”.

Then came her years in power and a depressing indifference, and worse, towards the Rohingya people and the well-being of the nation more widely. She fell from near-saintly status to cynical stooge in a shockingly short period of time – human rights hero to zero, and with nothing to show for it except human misery on an unprecedented scale in her country. Now she has learnt the hard way at what happens to those who think they can ride the tiger.

She has little defence. If she chose to come to an arrangement of convenience with the military, to win some influence and make some decisions, then she did not make the best of the opportunities available to her, to say the least. She might have chosen to lead, to speak out, to offer guarantees to prevent the attacks on those being murdered and expelled from their homes. That would have required the same steely determination and bravery that she had displayed in her long years of isolation, when she placed herself at the head of uprisings and demonstrations, and acquired her global celebrity.

She does not appear to have made much effort in making her old ideals reality. She slipped quickly into ethnic chauvinism and indifference to her own fellow citizens. Perhaps she was simply keen to regain the position and status lost by her father, premier of then-Burma, when he was assassinated by the army back in 1947, just before the nation became independent of Britain.

Today, so far from being showered with awards for her work in promoting human rights, Ms Suu Kyi would be fortunate to avoid a trial for crimes against human rights at The Hague . She has much to answer for, but whatever her fate may be, the real focus for the immediate future should be on the 860,000 Rohingya – traumatised and brutalised refugees who have fled to squalid makeshift camps in Bangladesh.

Hardly a wealthy nation, Bangladesh has found it difficult to cope with the influx, and the international community could do much more to relieve the humanitarian emergency. The usual hazards of the camps have now been joined by outbreaks of Covid-19, with little medical expertise, let alone vaccines, on hand to relieve the suffering.

If western governments are wondering what to do with their surplus vaccines, the camps of Bangladesh would be able to make good use of them. It is the pitiful plight of these people, rather than the piles of honorary doctorates, freedoms of cities and international awards, that will be the abiding legacy of the woman they no longer call “The Lady”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments