The government may come to regret taking a ‘light touch’ approach on AI

Editorial: It may in the end prove difficult to regulate the new technologies, but it seems odd that ministers have decided to pursue such a prosaic and piecemeal approach to AI given the enormity of what is already here

In the classic 1968 sci-fi movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, the onboard talking computer, HAL 9000, mutates from highly intelligent articulate utility to murderous quasi-human, a nightmarish scenario that shows signs of coming true.

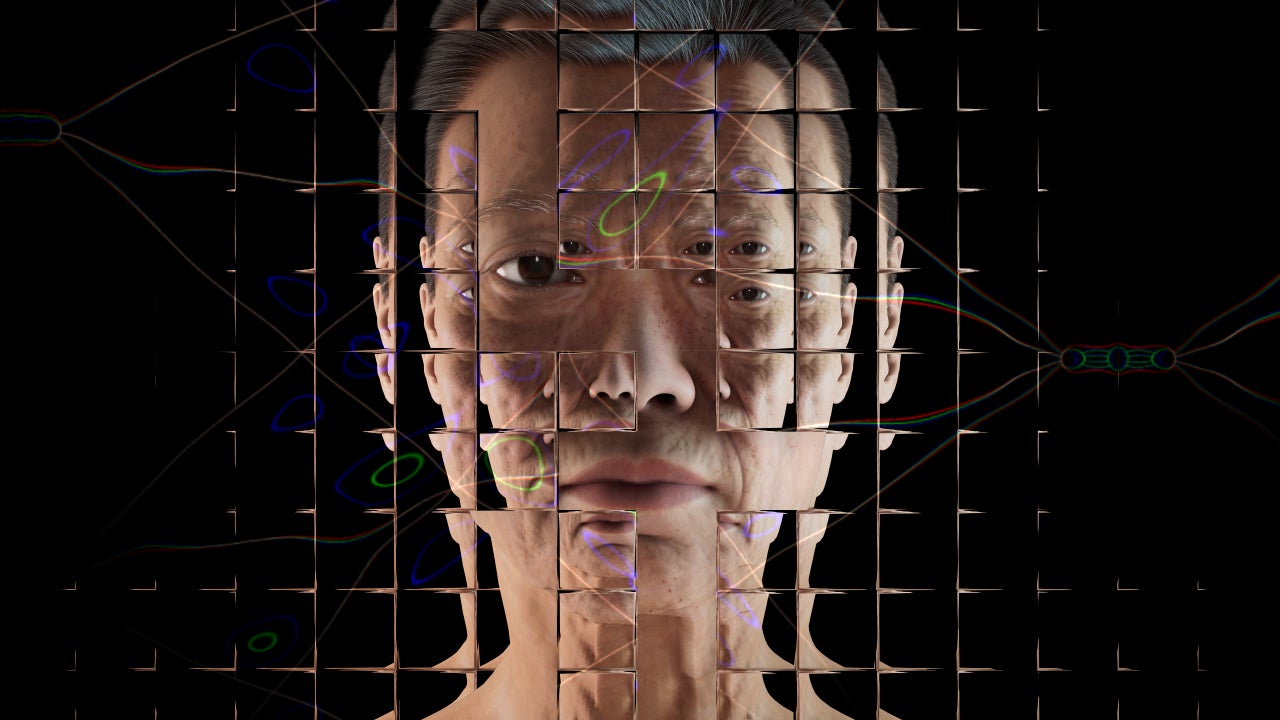

In the film, the terrified human crew try to turn off HAL (which stands for Heuristically programmed ALgorithmic computer, a sort of artificial intelligence machine), but it proves resistant to restraint. It is a situation that HAL’s designers didn’t quite foresee. This is roughly what humanity and its governments are now facing with the sudden rise of artificial intelligence – something that has been talked about since the earliest days of Alan Turing’s far-sighted research before the Second World War, but has now arrived with brutal force.

Even those most closely associated with the new technology have been surprised by its rapid development, and by its ability to generate everything from poetry to convincing-looking photographs to, yes, journalism.

In an echo of the aforementioned sci-fi film, even pausing the large language models (LLMs) that lie behind formidable AI software such as ChatGPT and Bard seems a hopeless task. Such LLMs are able to educate themselves at a rate far faster than humankind, because once one AI-enabled computer learns something, all the others do. It is as if, at the same moment as a brilliant mathematical scholar, after 300 years, managed to solve Fermat’s last theorem, every single person in the world instantaneously understood, digested and memorised their work. That is the power of AI, and it has launched itself upon the world like the atom bomb in 1945.

Hitherto, the British government, spying a rare “Brexit opportunity”, has favoured a “light-touch” approach to the new technology, in the hope of making the UK an “AI superpower”. This looks set to change, however. The government has announced a wide-ranging review of the impact of LLMs and AI. The Competition and Markets Authority will assess competition and consumer protection issues for companies using the technology, while other regulatory issues are to be devolved to the existing relevant watchdogs that oversee human rights, health and safety, and so on, rather than creating a new body dedicated to the technology.

This seems an inadequate initial response. The potential of AI is almost unlimited, and it will change everything, from self-driving vehicles and new works of art to selling investments, conveyancing, and curing people and animals of illnesses. There is a cosy assumption, embodied in the official “AI superpower” ambition, that AI is similar in quality to other revolutionary new technologies – steam power, electricity, mass production, flight, nuclear energy, and indeed computing, information technology and the internet.

That means that jobs will be created as well as destroyed, and, on balance, the latest scientific wonders can still be controlled and directed by humans. Yet the power of LLMs is of a different quality and order of magnitude to what has passed before, and the much-desired influx of jobs may not be created after all, because the LLMs are the ones that will be doing the work, and at a faster rate than any human can.

The brighter possibility is the final arrival of the kind of “leisure society” envisaged by the likes of John Maynard Keynes, HG Wells and Aldous Huxley, where the old challenges of increasing output and prosperity through human effort – the creation of wealth – are dissolved by the rise of the machines. Instead, humanity will have the problem of deciding how to distribute the economic dividends of the new technologies, and how to spend the free time after the abolition of work.

Will it be the owners of these new machines and their intellectual property who get to keep all the income and wealth thereby generated; or will we have a society in which the former workers, now unemployable, will receive an equal share?

Of course that is all fanciful, because it will be some time before even the dancing robots of today will be able to work in a care home or carry out a heart transplant, but the outlines of a brave new world are beginning to show themselves. It may in the end prove difficult to regulate the new technologies, but it seems odd that ministers have decided to pursue such a prosaic and piecemeal approach to AI, given the enormity of what is already here. The dangers are clear. LLMs are no more immune to error than old-fashioned early computers.

If they are collating, interpreting and learning vast amounts of language and information, then that doesn’t make their “judgements” sound. LLM systems are no less capable of generating and repeating conspiracy theories and political propaganda than Homo sapiens. They can bamboozle and defraud people of their money as well as any con man.

What would an AI-generated news report on, say, the war in Ukraine or the Channel migration crisis read like? To use a rather old but serviceable expression, the computers are prone to the problem of “rubbish in, rubbbish out”. And once LLMs learn moral or factual “rubbish”, how do they “unlearn” it?

Given such questions, there is a strong case, as with the challenges of the climate crisis, new medicines, and nuclear proliferation, for some form of international regulatory framework.

We are some way away from that, which is worrying given the speed at which LLMs are developing. That is the essence of the warning from the “godfather of AI”, Geoffrey Hinton, who recently resigned from Google. To him, the AI chatbots are “quite scary”: “Right now, they’re not more intelligent than us, as far as I can tell. But I think they soon may be.”

So far, the British government still seems to think that an uncoordinated “light touch” across myriad regulators is all that’s needed to keep an eye on things. The HAL of tomorrow may have different ideas.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments