The G7 meeting on Tuesday has two tasks. The first will be to coordinate a comprehensive and coherent response to the situation that has arisen around the emergency evacuation from Kabul. The second will be to start the long process of building a new approach for the west towards Afghanistan, and more generally towards the relationship between the “old” developed nations and the emerging world.

The first is a practical problem. The US inevitably remains the principal actor in this sad and savage drama. But other countries in the western alliance – including of course the UK, but also Germany, France, Italy and Canada – have, or have had, troops in Afghanistan. The effort is a test for the west, not only for America. There is a temptation to see this as a humiliation for President Biden, which unquestionably it is. Some of the statements he made in his press conference last Friday have been shown to be false. But the performance of the US president, however disturbing, is much less important than what happens on the ground.

Managing the evacuation is an operational issue. Competence in Kabul is vastly more important than politics in distant Washington, or indeed in London or Berlin. The west has to manage this better than it has to date, and that will require more negotiation with the new leadership of Afghanistan. A united approach from the G7 nations is vital. That is the immediate task.

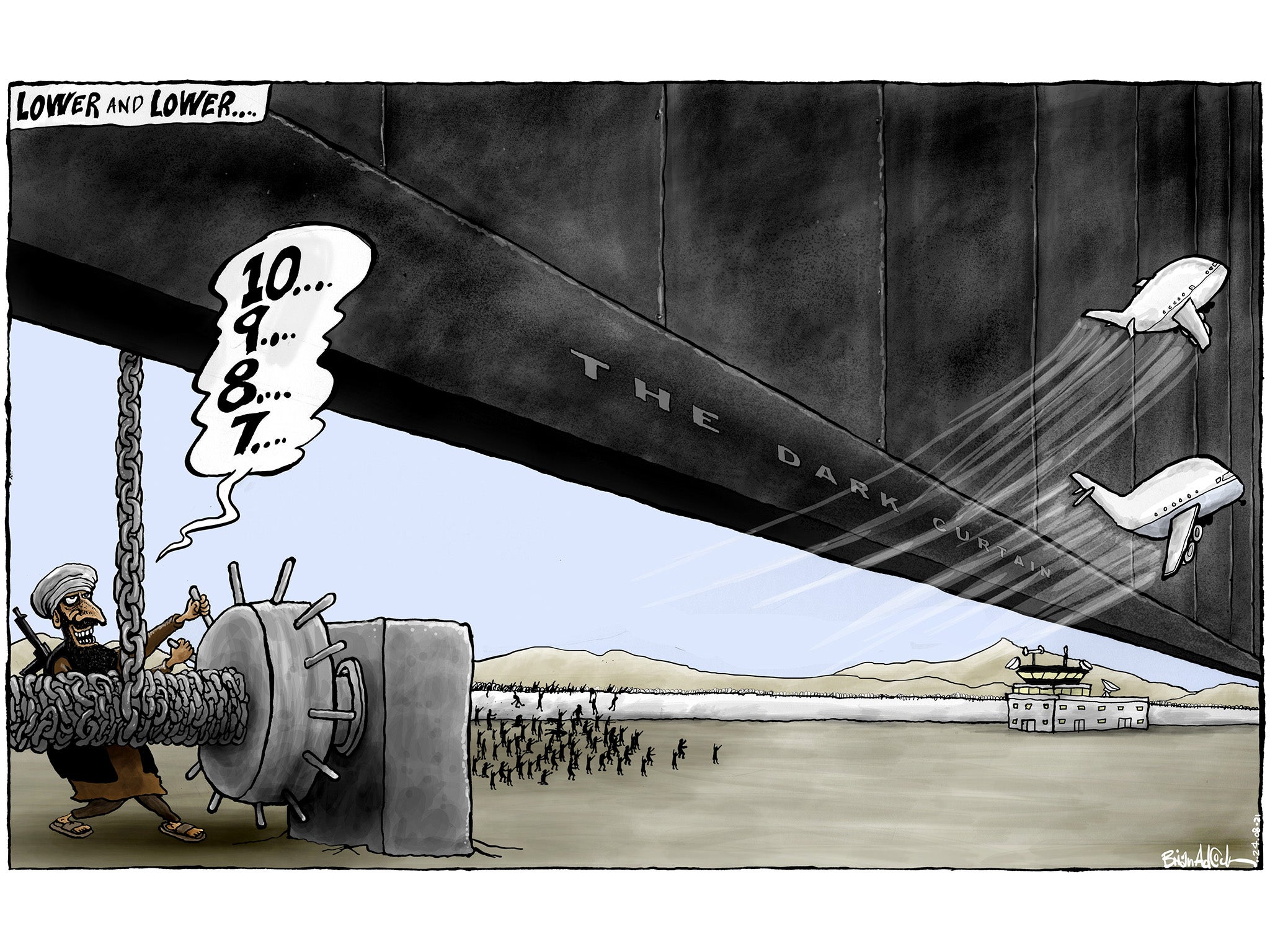

However, whatever happens in Kabul now, in a few weeks the US and its allies will have withdrawn completely from the country. This chapter of western involvement will be over. There will inevitably be a period of reflection about the mistakes that have been made. We must all learn from those. But the debacle is also an opportunity.

The west needs to reset its vision of itself. The G7 countries no longer dominate the world to the extent that they did when the group was formed in the 1970s, when they accounted for 80 per cent of the world’s economy. They need now to reflect on their diminished status, diminished further by the disaster in Afghanistan. But they still generate more than half of the world’s GDP. The US remains the world’s foremost military power. Europe remains the world’s second-largest economic grouping, smaller than the US but larger than China. Together the US and Europe will remain the drivers of the global response to the climate crisis.

One virtual G7 meeting, taking place in the middle of an emergency, cannot hope to do more than pose a series of questions – questions that need to be answered in a thoughtful and realistic manner in the coming months. These include practical ones. How does the west help the Afghan people now? How can the G7 best cooperate with Russia, India and China to ensure that none of the evident flashpoints around the world burst out into open conflict? And of course, how do we manage the refugee crisis that is taking place right now, in a humane and positive manner?

Beyond all this, though, the G7 leaders need to think about the role of their nations in a multi-polar world – a world where their countries self-evidently no longer call the shots. For example, does Joe Biden really echo Donald Trump’s “America First” line? Boris Johnson has to contemplate what “Global Britain” now really means, if anything. The next German chancellor will need to redefine policy towards both Russia and China. None of this will be easy. That is all the more reason to start this uncomfortable period of reassessment as soon as possible, and to do so in an honest and open way.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments