Like an A-level paper, this year’s results pose questions that may be difficult to answer

Editorial: The ‘Covid cohort’ of students have suffered from grade inflation and its supposed correction. But just how badly depends – unfairly – on what part of the country they are from

Congratulations to those who achieved what they needed, and commiserations to those who fell short.

Anyone who has ever sat an exam – which must be a universal experience – will well understand the emotions being felt by this latest cohort of A-level students. Given that they are too often derided by older, luckier generations, it’s worth acknowledging that the pandemic has had a serious impact on the education – and thus the life chances – of many who spent a proportion of their schooldays in Zoom and Teams sessions rather than in the classroom or the lecture hall.

Without rehearsing the arguments, even now many university leavers are awaiting their final degree award, delayed because of industrial action by academics. The lingering effects of the pandemic on the education of the young would make a fine proposal for a doctoral thesis. Perhaps one is already in train.

But the damage inflicted by the entirely necessary public health measures imposed during the Covid emergency has not been evenly spread. In terms of geography – a parameter that also serves as a rough proxy for social class – those in the North did worse than those in the South East of England, and that accords with both common sense and the anecdotal evidence that emerged during the course of 2020 and 2021.

Poorer families, already living in conditions unsuited to either private study or recreation, were probably even more disadvantaged by the switch to remote learning – and, for the youngest children, by the absence of early experiences of socialisation. Despite some efforts by the Department for Education, laptops were not universally available to those who needed them – but in better-off households, they were.

It is also true that fee-paying schools seemed to adapt to the new regime more readily than state schools. It all adds up to an exacerbation of existing educational disparities, and ones that do indeed go beyond geography and social class and into ethnicity.

None of that made social distancing or the imposition of lockdowns “wrong”, because the effects of even stronger waves of Covid during the pandemic would have made longer and harsher lockdowns inevitable, as well as costing more lives (albeit mainly among much older generations).

What does have to be recognised is the simple fact that the pandemic has cast a long shadow on the generation of Britons born after the millennium, and that not enough has yet been done to help those who lost out on vital elements of their school career to “catch up”. Such efforts as were made were swiftly wound up, a gesture of how little some in government seem to understand what has gone wrong in recent years.

Like an A-level paper, this year’s results throw up some questions that are easier to answer than others. It isn’t clear, for example, how the return to the normal marking of A-levels in England can be reconciled by prospective employers and university admissions teams with the deliberately inflated awards given to Welsh and Northern Irish applicants for jobs and places. Is an English B grade now worth the same as a Welsh A grade?

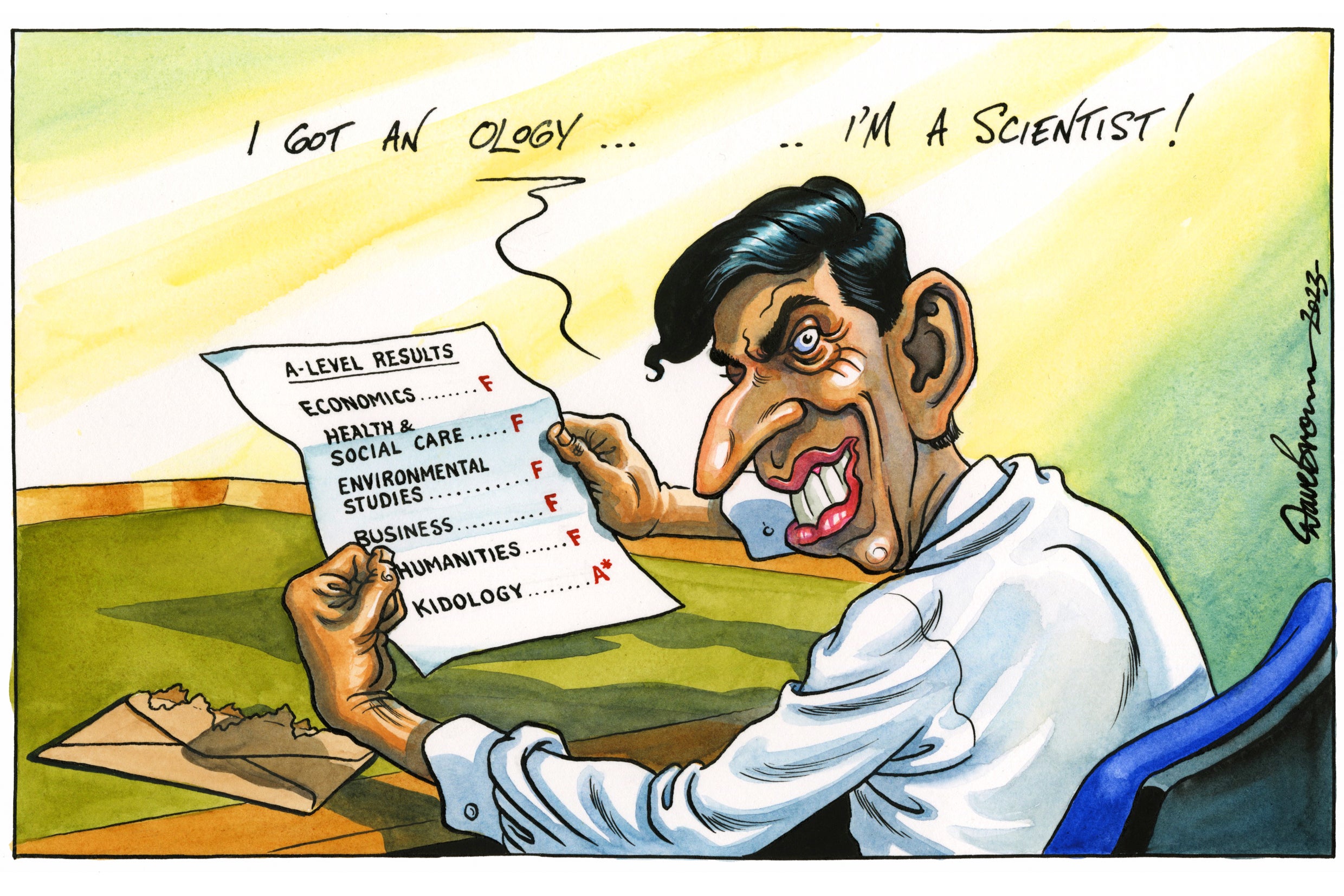

Much larger conundrums surround the future of higher education itself. Many universities have to attract lucrative foreign students in order to cross-subsidise the teaching of British undergraduates and the funding of research programmes. What, an examiner might enquire, is the optimal balance between these competing demands? And is Rishi Sunak right to find part of the answer in banning so-called “Mickey Mouse” courses (however these are defined)?

Such wider, more fundamental problems need to enjoy a higher profile in the public debate, given that the number of students from England embarking on a degree this year is set to slip by around 3 per cent.

The education secretary, Gillian Keegan, has landed herself in trouble by remarking that in 10 years’ time, no one will be much interested in someone’s grades as opposed to what they’ve achieved at university or at work. This is true, but good A-levels are the key that opens some of the doors, and it would be preferable if they were gained on a socially level playing field. That is a truth too little acknowledged by senior Conservatives.

If the higher education sector is forced to shrink in the coming years, then there will be many more disappointed teenagers seeing their favoured courses fall from their hands on days like this, and the broader consequences for growth and the economy from an intellectually less-well-trained workforce may be just as depressing. We need more investment in human capital – it is Britain’s most valuable commodity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks