How drag saved my relationship with my Muslim mother and made me fall in love again with my Arab heritage

My happy family life in the Middle East took a dark turn when I came out. But slowly, through the use of drag, I reconnected with my strict mother by taking inspiration from her

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Before I even knew what the word gay meant, there was so much to love as a child raised in the Middle East. My Arab family household was like Ru Paul’s Drag Race (but without the cameras and acknowledged queerness). When I was eight years old and it was past my bedtime, I used to sneak around the house and watch my Iraqi-Egyptian mother in fascination: the meticulous construction of her glamorous social costume, how with a dancer’s grace she’d usher in her guests, how she’d conduct her conversations like a trained performer.

When I think back to my pre-teen years in Bahrain and Dubai, I feel fuzzy inside; Arab households pride themselves on open door generosity and a constant flow of relatives (with subsequent yet loving family “dramas”), and there’s never a lonely moment.

But things took a dark turn when my sexuality became an issue. What I once loved about home life was clouded by the strict expectations of my behaviour as a growing Muslim “man”. A compulsory Islam tutor at home was a weekly source of fear; at the age of 11, he painted my (straight) twin brother and I vivid visual descriptions of hell, where any non-conformist or unholy behaviour would be brutally punished. And resultantly, throughout my teens, I was victim to a recurring nightmare in which God himself pinned me down on a metal bed and tortured me for my gay sexual fantasies.

My parents – who were brought up Muslim and in Iraq – were so worried about my developing sexual orientation that they sought to “protect” me from the inevitable inferno, grounding me when they discovered I bought the Brokeback Mountain DVD, for instance, or throwing away all my “effeminate” clothes.

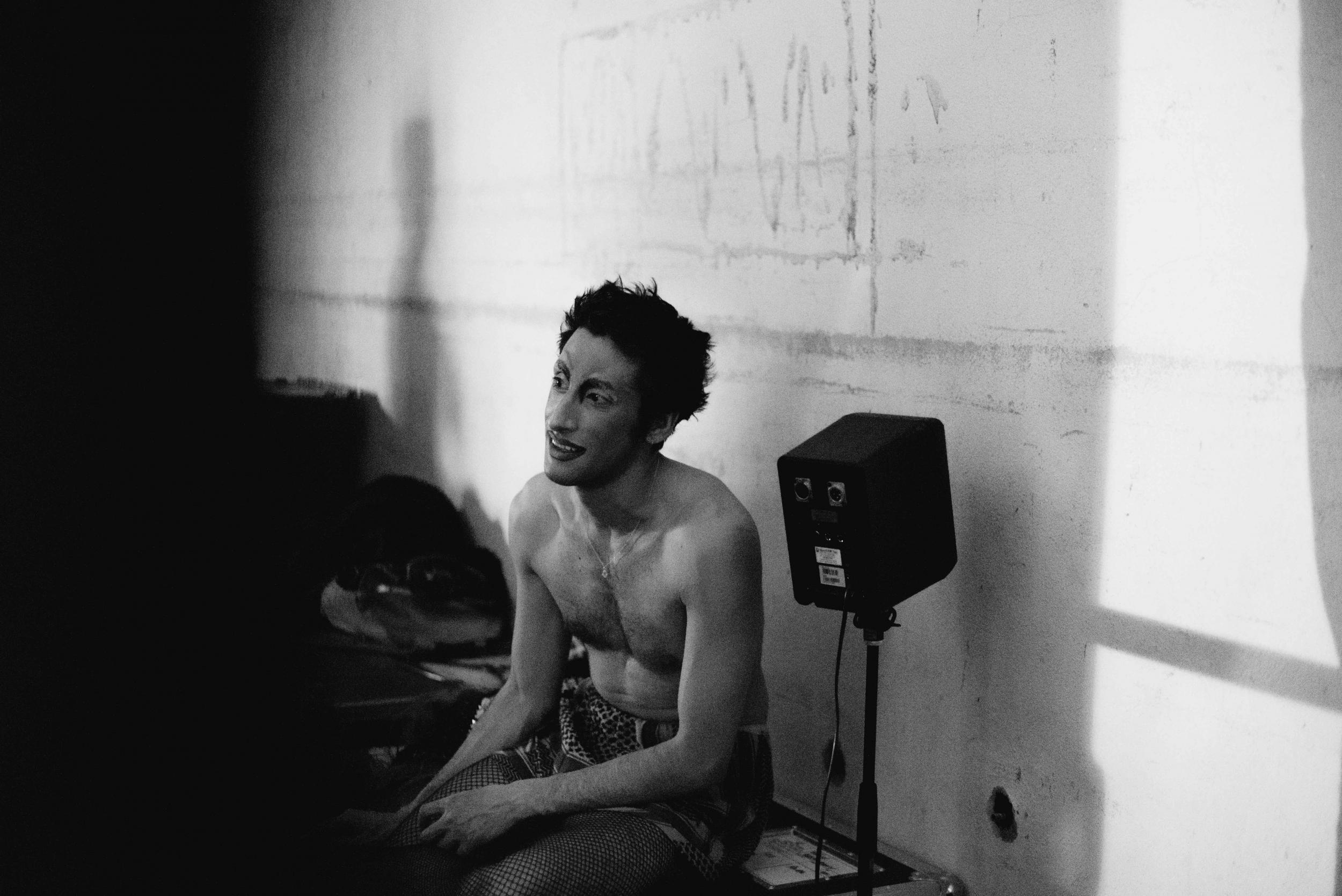

And now, at the age of 26, I’m a professional drag queen. After what was a traumatic coming out, I left home at 18 with as fraught a connection to my parents as you can imagine. And I made university my home away from home.

It was at Cambridge where I began drag, and set up my now musical comedy drag troupe, Denim. The sense of liberation I had as a student – where I could live and perform my sexuality and gender identity without familial reproach – was a profound emotional step for me. It is why I initially thought of drag as my “running away”. It was a way to transgress how I was taught a man should behave, and it was an act of self-creation that severed me from my upbringing.

But while I felt powerful in drag, I was still searching. I think it’s because my sense of empowerment felt forced, like a sparkly cork-stop on the anguish of rejection bubbling beneath. Rather than processing how I felt, drag was my armour – hence as the wig came off, I felt more vulnerable than ever before. And as I was quite literally shoving my drag in the closet when I visited my parents in the Middle East, drag became tied to further feelings of shame that I hoped it would eradicate. While moments in costume made me feel invincible and most “myself”, I found my general self-worth to plummet. Yet I couldn’t ditch the highs from feeling like a queer unicorn warrior when on stage as my drag alter-ego Glamrou.

It wasn’t until I met the remarkable Amnah Hafez that things started to change for me. A remarkable stylist and editor-in-chief of Cause & Effect magazine, Amnah is the only other “runaway Arab” I’ve met and gotten close to in London. Originally from Saudi Arabia, Amnah came to the UK from a background of even stricter gender expectations than I did. And through a stroke of luck, we met, and she eventually styled my drag troupe’s first music video.

Through Amnah I was reminded of all the wonderful elements of Arab culture that I was quick to denounce at 18 – the generosity, hilarity, love, openness, and implicitly drag displays of emotion. And it was Amnah who encouraged me to wear my heritage proudly in drag.

Since then, performing uplifting tropes of Middle Eastern femininity has been a key feature of my practice. Whilst I set out to reject my heritage through the queer art of drag, I’ve ended up falling back in love with it. And though my mother does not accept a large part of who I am, through performing what I love about her on stage, my wounds are healing. We’re in fact closer than we’ve ever been.

After all, I have drag to thank for rescuing the memory of my mother from when I was eight, peeping adoringly through the door crack, in awe of the ultimate Arab queen.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments