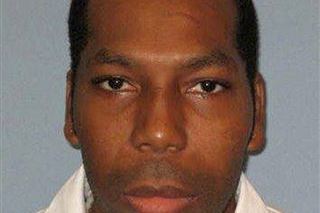

Dominique Ray died alone on death row — if he hadn't been a Muslim, it would never have happened

America is busy turning religion into a 'super right', but such efforts didn't extend to one man who wanted an imam in his execution chamber a few days ago

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Late at night on 7 February, Dominique Ray was executed in the death chamber by the State of Alabama. He died alone.

The killing by the state of another African American man in the death belt of the American South would not have usually drawn significant attention. But Dominique Ray was different. He died alone because he was Muslim. Had he been Christian, Alabama would have provided a state-employed Christian chaplain to give him comfort, hold his hand and prepare him for death in his final moments.

Ray’s execution was stayed by the conservative Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals. The Court found that there was a substantial likelihood he would prevail on his claim that Alabama’s policy violated his right to religious freedom.

Two hours later, in a 5-4 vote, the Supreme Court dissolved the stay in a one-sentence order, noting that Ray had waited too long to raise the argument. Ray had been given an execution date in November 2018; he petitioned the warden to have an imam present; the warden denied the request on 23 January 2019, and Ray filed his petition five days later. Ray had committed the crimes in 1999, when he was a teenager, and he had been on death row for 19 years. Justice Kagan, in dissent, called the lifting of the stay “profoundly wrong.”

The United States Constitution and federal statutes are profoundly protective of religious rights. The Establishment Clause of the Constitution prohibits discrimination among religious beliefs or between belief and non-belief: “The clearest command of the Establishment Clause is that one religious denomination cannot be officially preferred over another." This is an issue that was resolved at the time of the Constitution.

To be sure there were few Muslims in America at the time of the founding, although an estimated 20 per cent of slaves brought to the American colonies were Muslim. Thomas Jefferson’s religious freedom law of Virginia, approved in 1786, was the model for the First Amendment and was intended, Jefferson wrote, to “comprehend, within the mantle of its protection, the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and Mahometan [Muslim], the Hindoo [Hindu], and infidel of every denomination.”

Congress’ ostensible solicitousness for religious rights has also been reflected in statutes, including the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (“RLUIPA”) that applies to prisoners. A RLUIPA claimant must demonstrate a sincere belief and a substantial burden on his religious practices. At that point, the government must demonstrate that the infringing policy is the least restrictive means of furthering a compelling governmental interest.

There was no doubt that Ray was sincere in his Muslim beliefs and that being denied the spiritual comfort of chosen clergy at the hour of death was a substantial burden. It would be hard to envision a more critical or poignant moment for spiritual succour.

Alabama in Ray’s case simply argued that limiting the presence of a chaplain in the death chamber to state employees was in the governmental interest of security and that Ray could have a Christian chaplain in there if he wished. The state made no effort to consider other, less restrictive means, like obtaining the services of a Muslim military chaplain or Muslim chaplain with a history in Alabama prisons who is not on the state payroll, or employing a Muslim chaplain on the state payroll.

This Supreme Court has been in the process of enshrining religion as a kind of "super right" that takes precedence over other well-recognised rights. In the last term, Colorado cake bakers had a right of religious freedom to refuse to bake a cake for a gay couple if their religious beliefs prohibited gay marriage. These were the same arguments used to challenge the Civil Rights Act requirement that African Americans be served in restaurants and provided with public accommodations.

In the Hobby Lobby case, the Court found that corporations themselves had sufficient spiritual lives that they could not be compelled to provide family planning services. School prayer, state funding of parochial schools and abortion rights are all now within the sights of the religious right in the name of religious freedom. But no such protection of religious freedom was extended to Dominique Ray.

The Supreme Court’s 5-4 majority did not hold that Dominique Ray could not have a chaplain in the death chamber. They moved to the easy procedural cop-out of delay. After nearly a quarter-century on death row, and only a five-day delay after the warden denied Ray’s request, the death sentence had to be carried out now. The state’s right to administrative efficiency apparently trumped the right of religious freedom.

Presumably, the Court knew that it could not issue an opinion saying Muslims had no right to a chaplain when Christians did, or that Muslims had to use a Christian chaplain. But let’s review the recent history. My Guantanamo Muslim detainee clients were granted no right to religious freedom; they were not “persons” pursuant to the statute. A ban on Muslims was, according to the Supreme Court “neutral on its face” despite the fact that the president said over and over again it was a ban on Muslims. This is a record of differential treatment that cannot be hidden in legal obfuscation or technical procedural rulings.

Nearly a quarter-millennium ago, George Washington wrote in his letter to the Jewish Congregation of Newport, Rhode Island, “May the Children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree, and there shall be none to make him afraid.” Muslims, the Stock of Abraham/Ibrahim as well, should have the same rights, the same concern, especially “at the hour of our death".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments