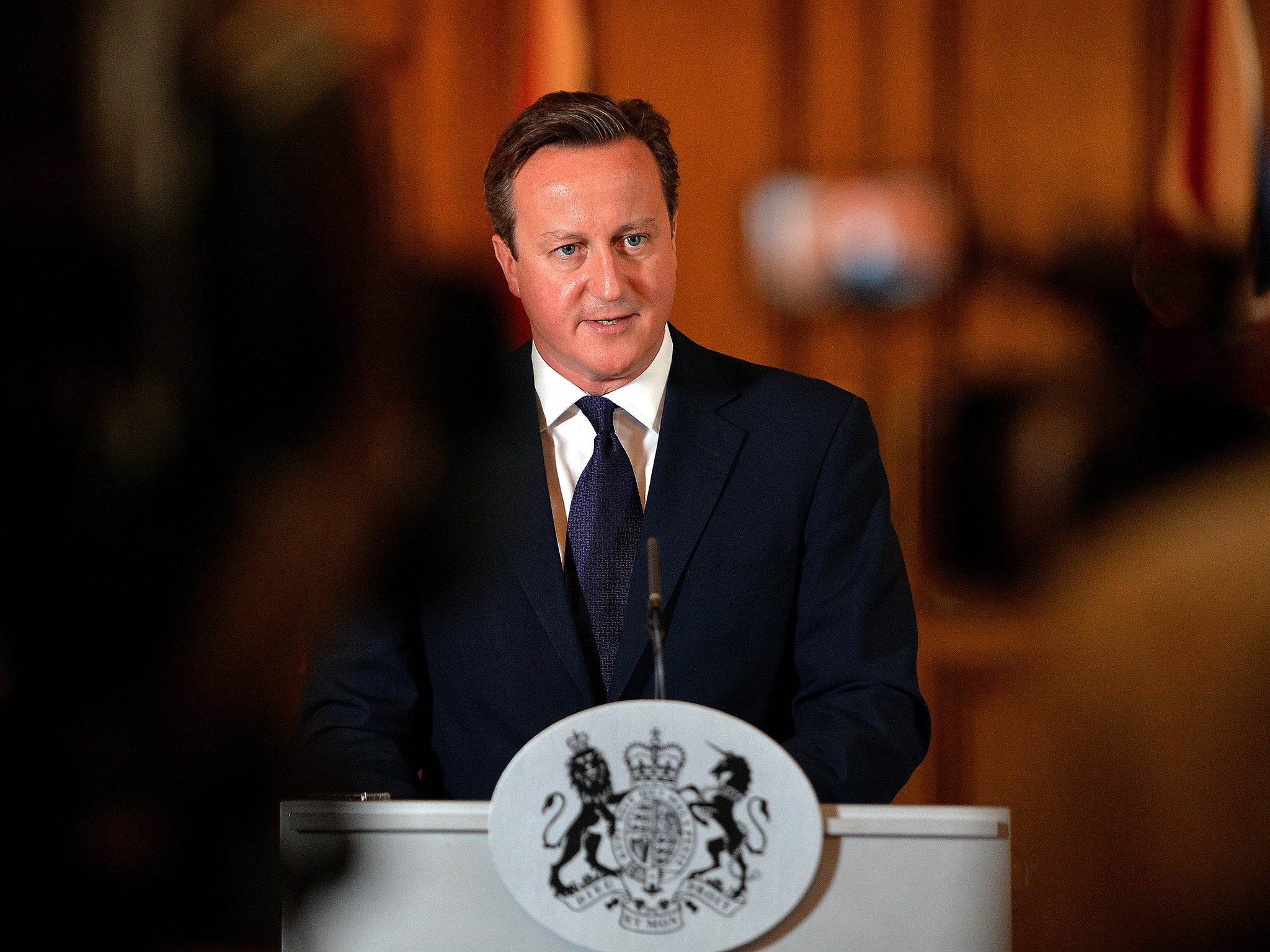

David Cameron’s legacy: a mix of warm words and cold cuts

To his credit, the Prime Minister wades into the difficult problems of troubled families and neuroscience

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Within hours of the publication of transcripts of conversations between Bill Clinton and Tony Blair last week, plausible spoofs were circulating on the internet. In one, Clinton explained that he found “punching a ham” therapeutic and that he would bring a ham the next time he visited. “We have ham here,” was the fictional Blair’s deadpan reply.

I was on my guard therefore, when I came across another Blair imitation on Friday. I was told about a speech given by the One Nation Prime Minister, towards the end of his time in office, setting out his “legacy agenda”. In it, he addresses the problem of poverty, although he rebrands it as “life chances”, and says he wanted to move away from the two old ways of looking at it.

Traditionally, he says, the left wanted to transfer money from the better-off, while the right thought that a rising economic tide would lift all boats. He wants to move beyond both: “It’s clear to me the returns from pursuing these two old approaches to poverty aren’t just diminishing, in some cases they’re disappearing in the modern world.” These “economic” methods miss the “human dimension to poverty”, he says. He wants to look at “the reasons people can get stuck, and become isolated”.

Yes, I was being told about a speech David Cameron is going to give tomorrow. It will be a classic Blair, third-way speech, on a subject supposed to be close to the Prime Minister’s patrician heart. It will detail some of the substance of the “big push on massive social issues” for which he hopes his government will be remembered.

A lot of the speech contains important thinking about social justice. He will not only try to steal Blair’s clothes, but he will try to take Nick Clegg’s too, pinching the wardrobe the Liberal Democrats wore in the coalition. It was Labour and then the Lib Dems who worried most about early years, parenting skills and the gap in child development between rich and poor. Now it is going to be the compassionate Conservatives. Suppress for a moment the thought that it was the coalition government that closed down many Sure Start centres: if Cameron wants to re-invent that wheel, those who care about inequality should welcome it.

Some of the speech will sound quite Conservative. The section on education will talk of character, service, perseverance, coming back from failure. I am told it will be “the opposite of the all-must-have-prizes culture”, although that might be quite Blairite too. But what is important and new is Cameron’s emphasis on mental illness and addiction. This sounds very different from the Conservative Party of the past, and is a mark of progress.

As a backbench member of the Home Affairs Select Committee long ago, Cameron was liberal and thoughtful about drugs, crime and punishment. As a prime minister in a hurry to leave his mark on history, he is going with the grain of social change in trying to change attitudes to mental illness and to reduce the stigma that often prevents people seeking help.

In all this, there is too an openness to evidence that is refreshing. He will quote Jack P Shonkoff, the Harvard professor of child development, and Robert Putnam, the author of Our Kids, about the growing divide in “social capital” in the US. It sounds like the Blair mantra, “what matters is what works”. If, however, policy is going to be led by evidence, the Prime Minister ought to be alarmed by official figures here showing a widening wealth gap in 2012-14 for the first time in 15 years.

Cameron could simply say that work is the best cure for poverty, for child poverty, and, often, for mental illness, and boast about his government’s extraordinary – and largely unintended – record in creating jobs. So, it is to his credit that he wants to go further, wading into the difficult and traditionally unrewarding problems of troubled families and neuroscience.

But still doubts creep in. Mental healthcare funding over the past five years has been too low, for example.

One of the big things that prevents centrist social democrats who are dismayed by Jeremy Corbyn from throwing in their lot with One Nation Conservatives is this: it is not that Cameron and Osborne don’t care about poverty and inequality; it is, as Philip Collins of The Times says, that they don’t care enough. They want to make it easier for the poor to help themselves, but when the poor do help themselves by working they see no contradiction in taking away the tax credits that lifted them up.

The planned cuts to tax credits have been scrapped, but the same cuts are still planned for new claimants of universal credit, as it replaces tax credits over the next four years. It is wonderful that Cameron wants to tackle the underlying, long-term causes of poverty, but it will sound like warm words if he increases the hardship of the working poor in the here and now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments