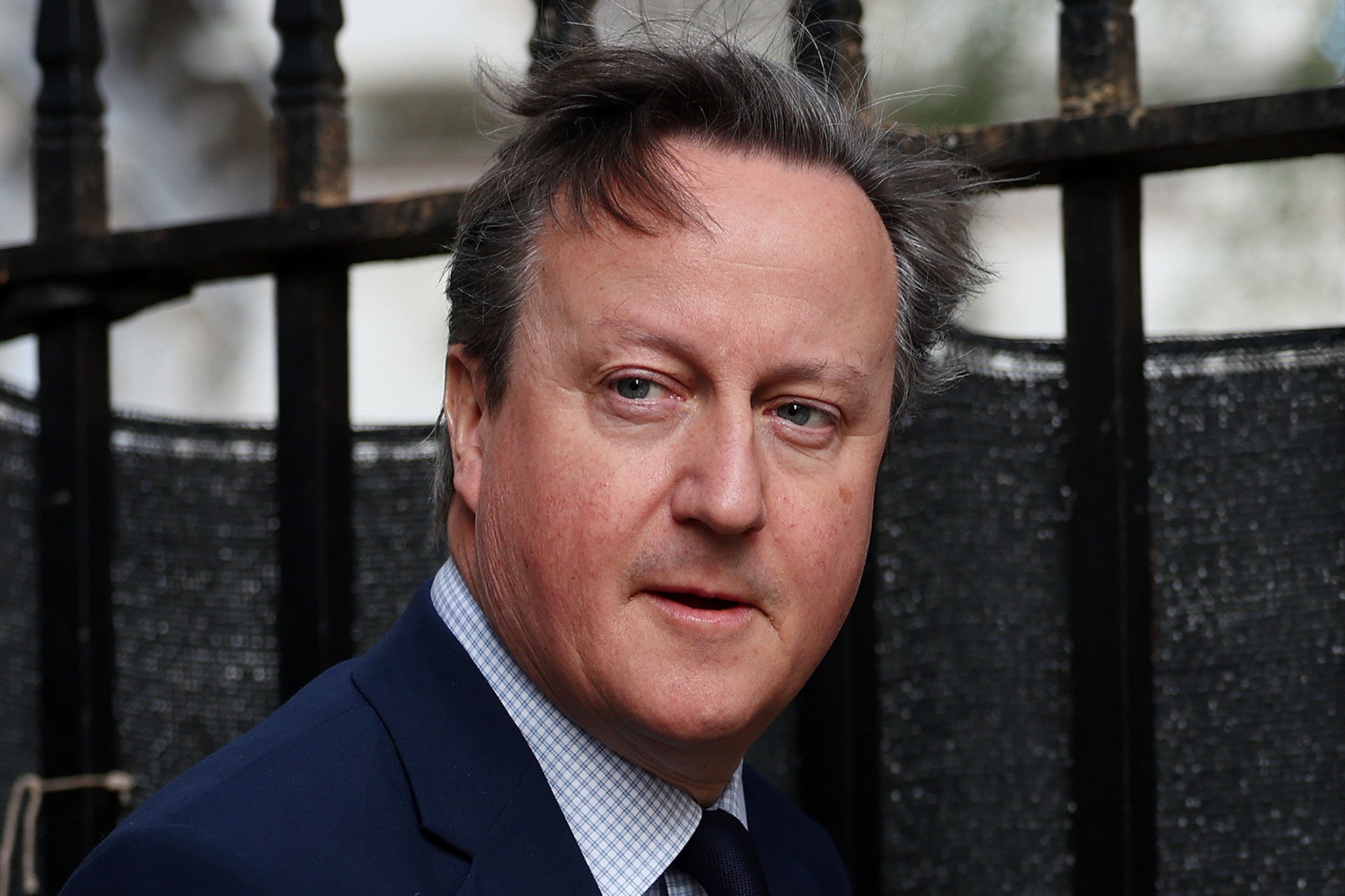

Smooth David Cameron was brought back to bolster Britain abroad – but it hasn’t worked

The former prime minister was supposed to add some heft to foreign policy. Ahead of the G7 summit, John Rentoul looks beyond his silky communication skills and asks: what’s he really achieved?

David Cameron “knows he’s got a limited time to make a difference – and he’s really going for it”, according to Peter Ricketts, the crossbench peer who served as national security adviser in the coalition government.

It was a great coup for Rishi Sunak to recruit the former prime minister as foreign secretary – who can forget the yelp of surprise from Kay Burley on Sky News’s live coverage when old smoothie-chops himself emerged from the car in Downing Street in November’s cabinet reshuffle.

There was certainly a strong case for using Cameron’s silky communication skills and personal contacts with world leaders to upgrade Britain’s presence abroad. Not that James Cleverly was doing a bad job – some Foreign Office officials who were initially sceptical about him, thinking him a lightweight, were surprised by how good he was at a glad-handing role that he so obviously enjoyed.

But serious times called for heavier firepower. That seemed to be Sunak’s thinking. Britain’s response to the crisis in Gaza, in addition to the war in Ukraine, would benefit from being represented abroad by a former prime minister. Awkward questions about the threat from China – with which Cameron had as prime minister declared a new “golden era” of relations – were pushed to one side, as were any leftover doubts about Cameron lobbying his former colleagues on behalf of Greensill.

But how has Cameron actually fared as foreign secretary? What difference has he made? He continued the slow shuffle of changing forms of words on the question of calling for a ceasefire in Gaza – from a “humanitarian pause” to a “sustainable ceasefire”, as the British government tracked the Biden administration’s policy closely.

Support for Israel tempered by calls for restraint and demands for aid to be let into Gaza continued to be the British line. It was tested severely when the Israeli Defence Forces killed seven aid workers, including three British nationals, two weeks ago. Cameron navigated the diplomatic minefield as adroitly as you would expect, but as he and Sunak were unwilling to suspend arms sales to Israel, it was mostly for show.

Cameron’s great strengths were on show at the Nato summit last week, celebrating the alliance’s 75th anniversary. He joined in a lot of brave talk about how Europe was prepared to shoulder a greater share of the burden of supporting Ukraine, and that this was the answer to the bluster from Donald Trump, threatening to cut US funding.

Cameron recorded a celebrated video, walking through the conference centre, delivering an account of himself straight to camera. Yet that video also recorded his weakness, in that he claimed that he was about to go to Washington to talk to Mike Johnson, the Republican House speaker, to try to persuade congressional Republicans to unblock funding for Ukraine.

But when Cameron got there, Johnson’s diary proved mysteriously unable to accommodate the foreign secretary. To make matters worse, Jake Sullivan, Joe Biden’s national security adviser, downgraded a meeting with Cameron to a phone call. The foreign secretary flew all the way to Washington to make a phone call – and that was with people with whom he agreed.

If Cameron hadn’t overclaimed in advance, the trip would have been a success. The foreign secretary dropped in on Mar-a-Lago, Trump’s home in Florida, on his way to Washington. This was a breach of the usual protocol of avoiding contact with opposition politicians during election campaigns, but made good sense in that you have to go into the tents of the ungodly if you want to change the world. Trump himself is the main obstacle to US support for Ukraine, even if he never returns to the White House.

And Cameron met Antony Blinken, the US secretary of state, holding the usual joint press conference.

But the sense lingers that Britain is a minor player. The Royal Air Force was allowed to join in US efforts to help Israel shoot down Iranian missiles and drones at the weekend, but it was a subsidiary role.

Sunak was guilty of overclaiming too. He said in his statement in the Commons on Monday that he was about to speak to Benjamin Netanyahu on the phone – a call that did not take place until the following afternoon. When it did, it was the minimum expected of both sides, as Sunak urged restraint and the Israeli prime minister presumably thought to himself, “Whatevs.”

An anonymous Foreign Office official quoted by Politico said that Cameron “gives the impression of being a man in a hurry – he knows he only has four or five months left and wants to make it count”. Another official suggested that this “makes him less constrained and operate with a greater risk appetite”.

So far, however, he has taken the risk of advertising meetings in advance that haven’t taken place – suggesting that bringing back a big cabinet beast has ended up only advertising Britain’s diminished role in the world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments