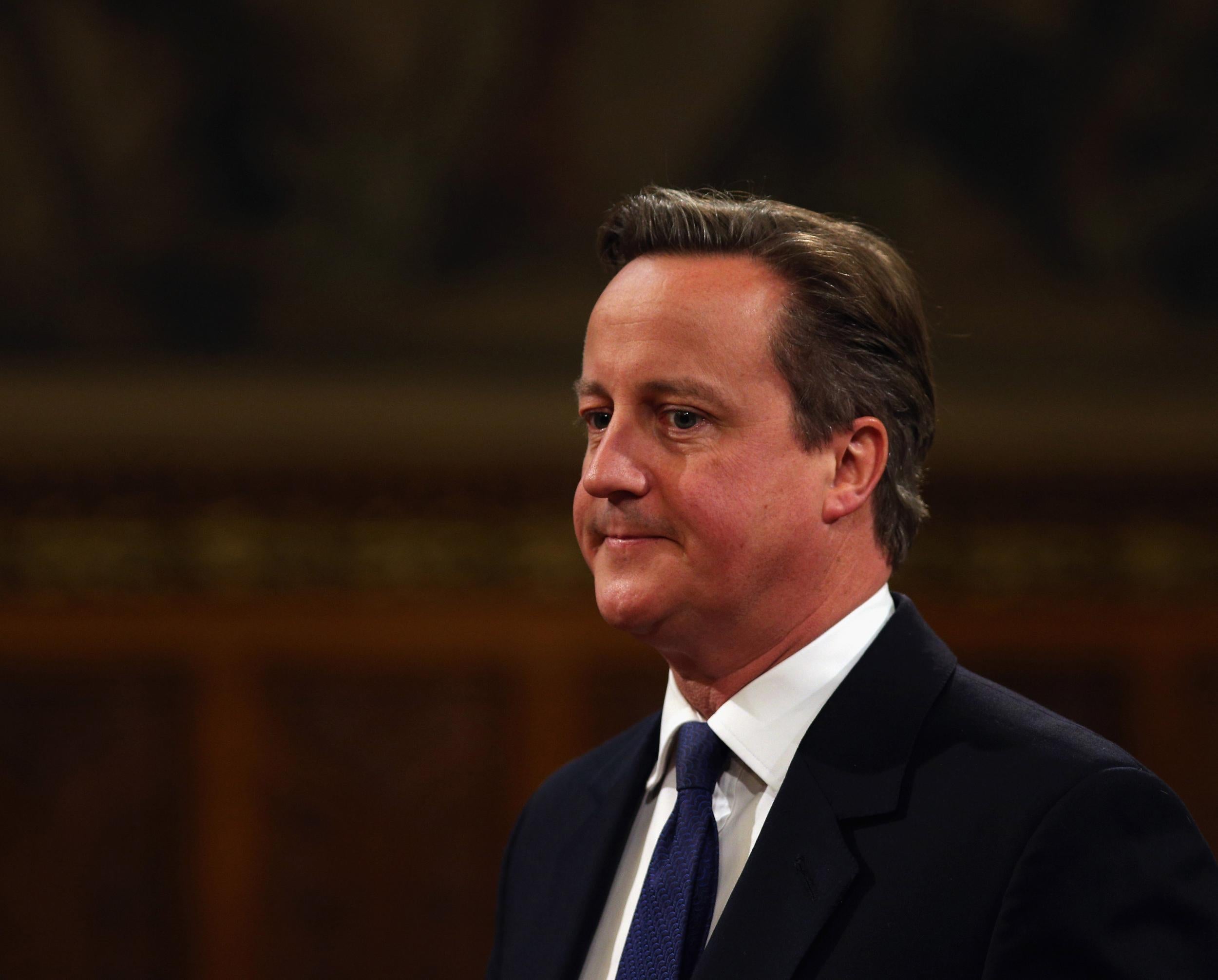

David Cameron faces much larger obstacles than the Lords to control the UK

Osborne’s Budget charter compels him to deliver a speedy surplus; the charter is the source of all his difficulties

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.After the euphoria of winning an unexpected majority at the election, the Government discovers how difficult it is to govern. In spite of the centrism that casts a spell over parts of the non-Conservative media, some senior ministers seek radical change: the proposal to cut tax credits from those on low incomes is not an aberration but part of a wider pattern.

In some respects, ministers are less patient and expedient in their determined ambition than the Thatcher administrations of the 1980s. Charles Moore’s second volume of his biography on Margaret Thatcher brings to life the nervy caution that lurked sometimes behind her public proclamations of steely resolution. Only towards the wild end would Thatcher have rushed into such an ill-judged policy as a steep and sudden cut in income for the working poor, though compared with Cameron and Osborne she had far more political space to do as she pleased.

Thatcher led a landslide majority and faced far fewer checks and balances. Yesterday’s battle between the Government and the Lords is only one example of a constraint on power, and in some ways the least significant. The Lords has often acted as an obstacle, or potential obstacle, to governments. Over this Parliament the Lords will leap selectively and, as we have seen with the tax credits, a lot of agonising accompanies attempted acts of defiance.

What is different for this Government is the wider political landscape, unrecognisable compared with the last time a radical Conservative majority ruled. When Thatcher made waves in the 1980s, the entire UK was swept along with virtually no intervening agencies to offer shelter from the storm. She abolished the locally-elected metropolitan authorities in England, including the GLC in London. There was no Scottish Parliament. There were no assemblies in Wales or Northern Ireland. The rest of local government in England was reduced to near powerlessness, with derided “loony left” councils failing to act as credible alternatives to central government.

Now the situation is transformed. The Conservatives might have won a small majority at Westminster but they cannot rule the UK in the way they, or indeed other parties, used to. Politics is viewed on the assumption that a Conservative Government rules mightily against a Labour party in disarray. There is plenty of ammunition for such an assumption, but take a step back, look around the wider UK and a subtler, complex picture emerges.

In Scotland, the dominant political figure is Nicola Sturgeon. At Westminster, the SNP parliamentary party already acts as a barrier to the mighty rulers. In July, the Government dropped plans to relax the fox-hunting ban when SNP MPs declared they would vote against. And if Cameron decides to back expansion at Heathrow Airport he will face the opposition of the London Mayor, Boris Johnson, and Johnson’s successor too. The Mayor does not have power to prevent the Government going ahead if it chooses, but does hold the authority of electoral victory in the capital. Johnson has used the platform to urge a rethink on tax credits; he will shout more loudly if Heathrow gets the go-ahead.

In the 1980s, there were no platforms for alternative public figures to acquire authority. Briefly, Ken Livingstone had a stage at the GLC – one that he used effectively to challenge the government. The platform was removed. Local government is also now very different across England. Although relatively powerless compared with their counterparts in other EU countries, some councils are becoming more influential. Labour council leaders in the north of England, and some in London, are widely respected. Osborne’s ‘Northern Powerhouse’ project comes with many strings attached, but elected Mayors will wield power and acquire platforms to challenge the elected Westminster government. City councils (especially Manchester) are acquiring additional responsibilities, limited and with more spending cuts to come. But some council leaders rule constructively in England’s big cities and their personal authority grows.

Let us not get carried away. The election to win is the UK general election. The fixed term parliament makes victory all the more worthwhile, power almost guaranteed for five years even with a tiny overall majority. Much power still resides at the centre even with all the talk, much of it imprecise, about the virtues of devolving power. But think of the agonies of John Major’s government after its 1992 win, the fearfully slow, cautious incremental reforms of Labour’s landslide government in 1997 and the compromises that arose when two parties ruled in coalition from 2010. The current apparently liberated government faces more constraints than any of those: a tiny majority in the Commons, no majority in the Lords, powerful independent figures in London, Scotland and in local government.

The Government is in “listening mode” over tax credits. It will have no choice but to listen on other policy fronts. Osborne’s Budget charter compels him to deliver a speedy surplus; the charter, and not his sensible attempt to move from high welfare subsidies to higher wages, is the source of all his difficulties. The rush to surplus means the spending review is proving to be painful. Tax credit cuts are getting all the attention, but the police fear unsustainable cuts of up to 40 per cent, while social care could be hit deeply at a time when hospitals cannot cope, two examples of many that are causing considerable anxieties behind the scenes in Whitehall and beyond. Consider the range of bodies and individuals who might speak out as cuts are announced: newly-empowered council leaders? The London Mayor? The Scottish First Minister? More forceful select committees at Westminster? A few Tory MPs, enough to wipe out a puny majority?

A government with radical ambitions faces more barriers than other recent daring or expedient administrations. The Lords are not alone.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments