All of us who watch this brutal – but thrilling – sport are responsible for what befell Damar Hamlin

NFL long accused of ignoring dangers of sport and controversy driven by race and class

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.You should watch it. It is really disturbing. And that is the point.

After 24-year-old Damar Hamlin of the Buffalo Bills makes the clattering tackle, he quickly gets to his feet. He seems to be fine. But after two steps, he collapses, tumbling to the pitch, unable to move.

We know that medical personnel who rushed on to pitch had to restart the player’s heart, before he was evacuated by ambulance and taken to hospital, as players from both the Bills and the Cincinnati Bengals sat or prayed, utterly distraught.

The young man was said to be a critical condition at the University of Cincinnati Medical Centre, where he has been sedated and is undergoing “further testing and treatment”.

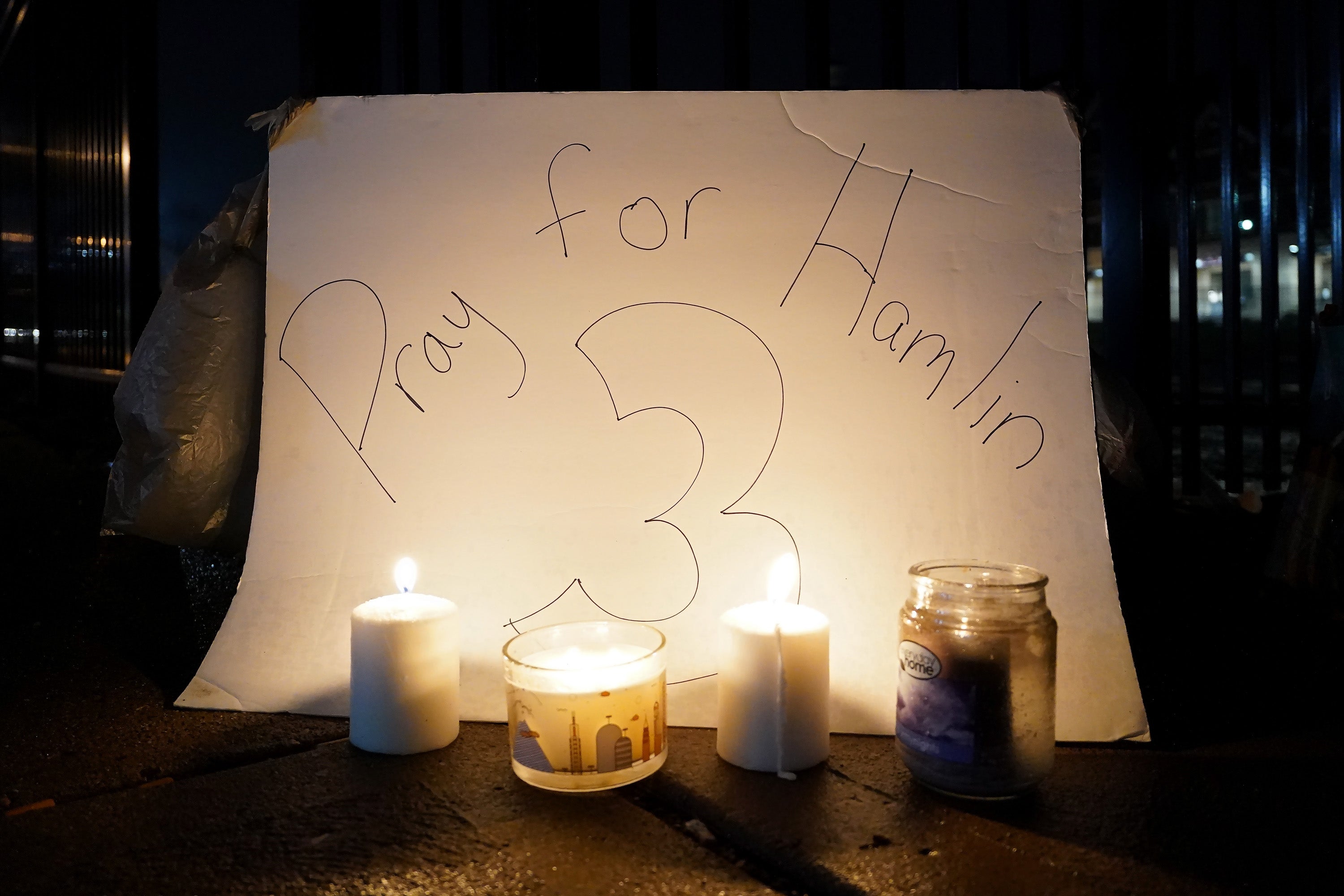

There was flood of emotional messages of support from fans and players alike, wishing Hamlin a swift recovery, not least from Tee Higgins, the Bengals player he clattered into. “I’m praying that you pull through bro. Love,” he wrote on Twitter.

But is that it? Is that all that is going to happen? Is that the only soul-searching that is going to take place after this game, that was reportedly only called off after the accident, after the intervention of the two coaches.

The truth is that American football, especially the high-impact, highly drilled version involving strong, intensely trained, fast professional athletes, is inherently dangerous.

Sadly, it is the dangerous parts – the tackles, the collisions, the sacking of a quarter back before he gets the ball away and is swamped by a sea of opponents – that help make it so utterly compelling.

“The hardest part about taming today’s NFL is that the sport’s very foundation is built on violence,” journalist Jeffri Chadiha wrote for ESPN back in 2012.

Chadiha, who now writes a column for the NFL official home page, added: “The most successful teams intimidate and brutalise their opponents, devouring their will.”

People have known that the sport was dangerous for a long time. In the early 2000s, Dr Bennet Omalu, a Nigerian-born forensic pathologist based in Pittsburgh carried out an autopsy on the body of “Iron Mike” Webster of the Steelers.

Omalu – played by Will Smith in the 2015 movie Concussion – discovered that Webster was suffering from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a progressive degenerative disease, that had previously been associated with “punch drunk” boxers and victims of brain trauma.

His work inspired others, including neuropathologist Ann McKee from the VA Boston Healthcare System.

In 2017, the largest study of its kind found 87 per cent of former football players who suffered mental symptoms, including mood swings and depression, had CTE.

Of players who competed in the NFL it was 99 per cent. (Their brains had been donated for research after their deaths.)

All the while, the NFL sought to play down the dangers. In their book League of Denial, Mark Fainaru-Wada and Steve Fainaru accused the NFL of covering up the “concussion crisis”.

The NFL has made some minor changes: players who are hit hard or appear to have any head injury are taken off the field and evaluated immediately for a concussion, and it has sought to ban “dangerous hits”, including intentional strikes on the head.

But it is obvious how limited these steps are: is a team coach, or an individual player, the most neutral decision maker? Of course not. He wants to get back on the pitch. And lots of tackles, and repeated clashes, go on as ever before. It is the nature of the game.

There is a racial and class element to the story as well. For decades, professional sports such as basketball, and American football, have been seen as potential routes to a well-paid job, and a sponsored college education, in the way that boxing once was, especially for the less privileged in society.

Yet across America, many middle class parents are pulling their children out of sports such American football and enrolling them in soccer. There is an even more egregious racial, and racist, part to this controversy. Back in 2013, the NFL reached a $765m deal to compensate up to 18,000 retired players who said they had suffered brain damage.

But for several years, the NFL sought to claim that the mental abilities of Black players was lower than their white counterparts, seeking to pay less because they claimed they started with lower cognitive function. It was only in 2021 – two years ago – the NFL Associated Press stopped the use of so-called “race-norming” that made it harder for Black retirees to show a deficit and qualify for an award.

We know all of this and yet the NFL thrives. Every week, millions head to stadiums or bars, or tune in at home to watch this human combat, our own version of the colosseum, albeit with cheerleaders. The Super Bowl has effectively become a national holiday, while the NFL, made up of 32 teams, is estimated to be worth more than $100bn.

If we wanted to make the sport safer we could. People might complain about some of the changes that could be made, such as eliminating kick-offs, which invariably result in a dangerous pile-on.

Having a real concussion protocol would help as well. In October, Miami Dolphins’ quarterback Tua Tagovailoa suffered back-to-back head injuries in a week.

The team claimed his wobbling after the first hit was a back injury, and he was allowed to play on. He also appeared days later, and was struck again in the head, and had to be carried from the field.

Why not have independent doctors involved in these decisions, especially given his team claimed he was stumbling because of back injury?

We know all of this, and yet we still tune in week after week.

Have we really reached the point where we consider a person risking their life is worth an hour’s entertainment?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments