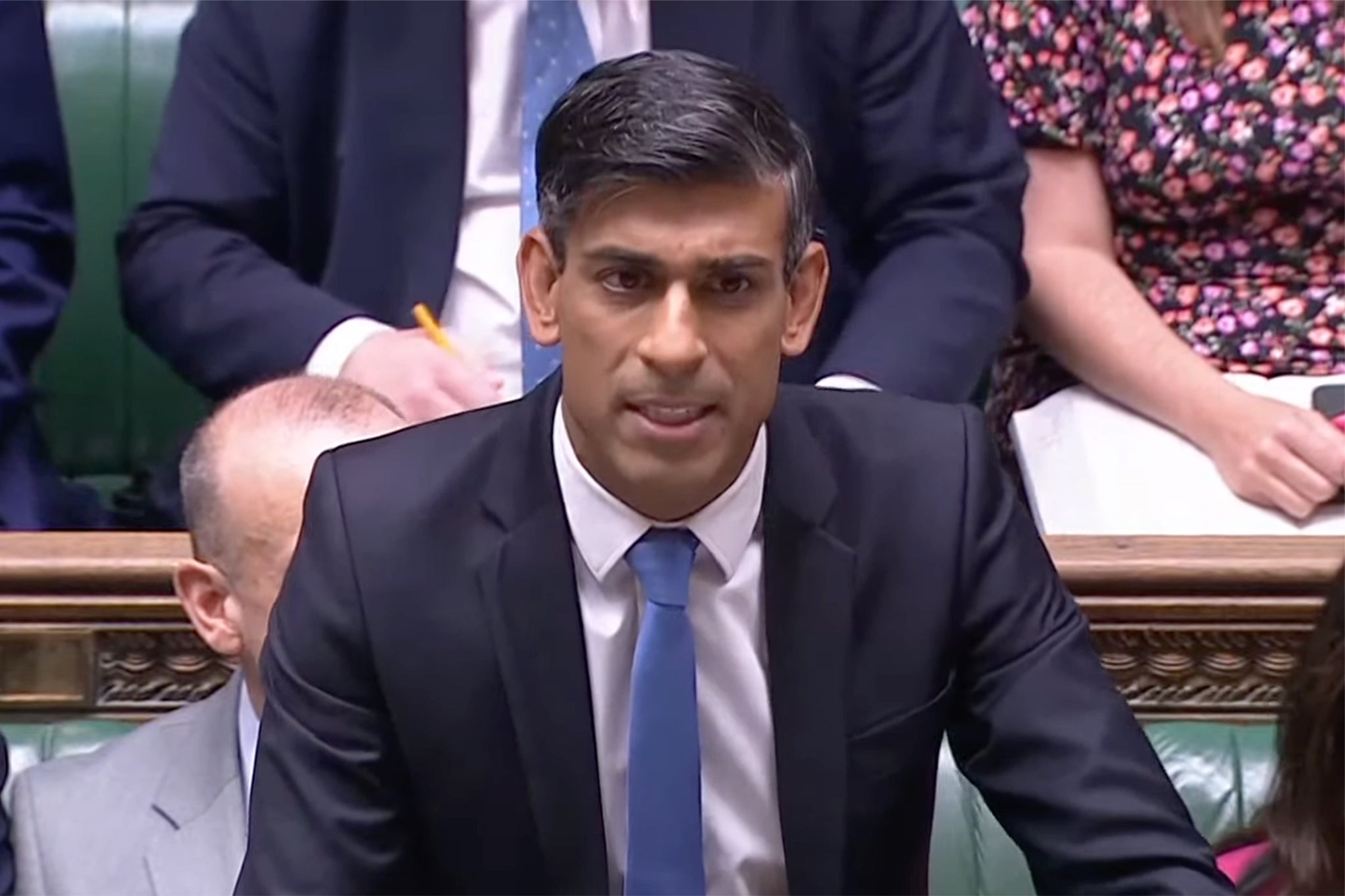

Crumbling concrete is Sunak’s poll tax moment

We may look back on the school buildings crisis as more than just a symbol of a disintegrating administration – but the moment the Tories lost the election, writes Andrew Grice

There are times when a government loses its authority in such a hugely symbolic way that a sea change which will sweep it away in an election defeat becomes inevitable.

Rubbish piled up in the streets during the 1978-79 “winter of discontent” was an image that haunted Labour long after Margaret Thatcher’s 1979 election victory. As James Callaghan, the Labour prime minister she defeated, admitted to an aide before the election: “There are times, perhaps once every 30 years, when there is a sea change in politics. It then does not matter what you say or what you do. There is a shift in what the public wants and what it approves of.”

Sometimes, it’s personal: Thatcher stubbornly sticking to her hated poll tax spelt the end of her premiership. Her successor John Major and the Tories never recovered their economic credibility after Black Wednesday, when Britain was booted out of the European exchange rate mechanism. An inevitable defeat at the following election brought an end to 18 years of Tory rule.

Today, crumbling concrete in schools could become the symbol of another dying administration and a country that wants change. It has handed Labour a perfect metaphor for a “broken Britain,” with creaking public services after 13 years of Tory government.

For a year, Tory MPs have been privately warning ministers about the danger of a “nothing works” narrative. Many Tory backbenchers returned from their summer break this week in a downhearted state, resigned to their party losing power next year. They know the schools disaster has reinforced Labour’s “time for change” message and Keir Starmer’s criticism of “sticking plaster” solutions.

Labour can also point to sewage in rivers and the sea, lengthening NHS waiting lists and last week’s air traffic control shambles. Strikes on the railways and in hospitals add to the picture. Birmingham City Council’s financial crisis raises the question of central government cuts to local government. It’s not an isolated case; some Tory councils are also in trouble.

Many controversies consume Westminster without being noticed by the public. The current crisis, beautifully timed for the start of a new school year, will definitely cut through. Tory ministers are past masters at blaming someone else for their failures – whether civil servants, “lefty lawyers,” judges, trade unions and in this case Gillian Keegan ludicrously pointing the finger at school heads – but this time there is no one else to blame.

Thirteen schools in England included in the Labour building programme axed by the incoming Tory-led government in 2010 now have crumbling concrete. Rishi Sunak was not an MP then, but as chancellor, he cut the programme from 100 to 50 refurbishments a year, so this is uncomfortably close to home. He has form on education spending: ministers recall how he brutally “stitched up” Gavin Williamson, the education secretary, in a last-minute dilution of the proposed £15bn catch-up programme after the pandemic.

What’s emerged so far might be merely the tip of an iceberg, with faulty reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (Raac) likely to be discovered in more schools, hospitals, care homes, courts, prisons, other public buildings and possibly social housing.

Ministers should be reminded of a golden rule of politics: the buck stops with them. You can’t devolve a crisis to academies or free schools (whose growth has meant less money for building projects at other schools). When the s*** hits the fan, as Keegan might have said, people look to their government to clean up the mess.

The education secretary’s sweary outburst and her frustration at not getting credit for doing her job smelt of the arrogance of power. Tory MPs are selling shares in Keegan only three months after she set out her future leadership credentials in a speech – at a conference to remember Thatcher, of course. This is the week she joined the list of ex-future leaders.

Another sign of a government on the way out is that it loses control of the agenda. This week’s “narrative” was supposed to be about better-than-expected economic news, as Sunak told his cabinet yesterday. But the government has trumped itself through its woeful response on crumbling concrete.

Bizarrely, the Tories claimed Starmer’s shadow cabinet reshuffle was evidence of “more of the same old short-term approach to politics which has failed this country”. The aim is to prepare the ground for a relaunch in which Sunak will argue he is tackling the long-term problems other politicians have ducked. A bit rich given the Tories’ short-termism in delaying school building schemes.

Crisis management is part of the business of government. But when a crisis comes to symbolise a government’s wider failure, it’s impossible to turn the tide. I think the one afflicting our schools might well prove such a defining moment.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments