Liberal Tories are in a gloomy mood – and they’re plotting rebellion

Centre-right Conservatives may find a home for themselves outside of the party, writes Andrew Grice. However, breaking up is hard to do – and in politics, it rarely has a happy ending

The liberal wing of the Conservative Party, which has been too nice and too quiet for its own good in the past few years, decided recently to launch a fightback against the noisy right-wingers who dominate the party’s debates.

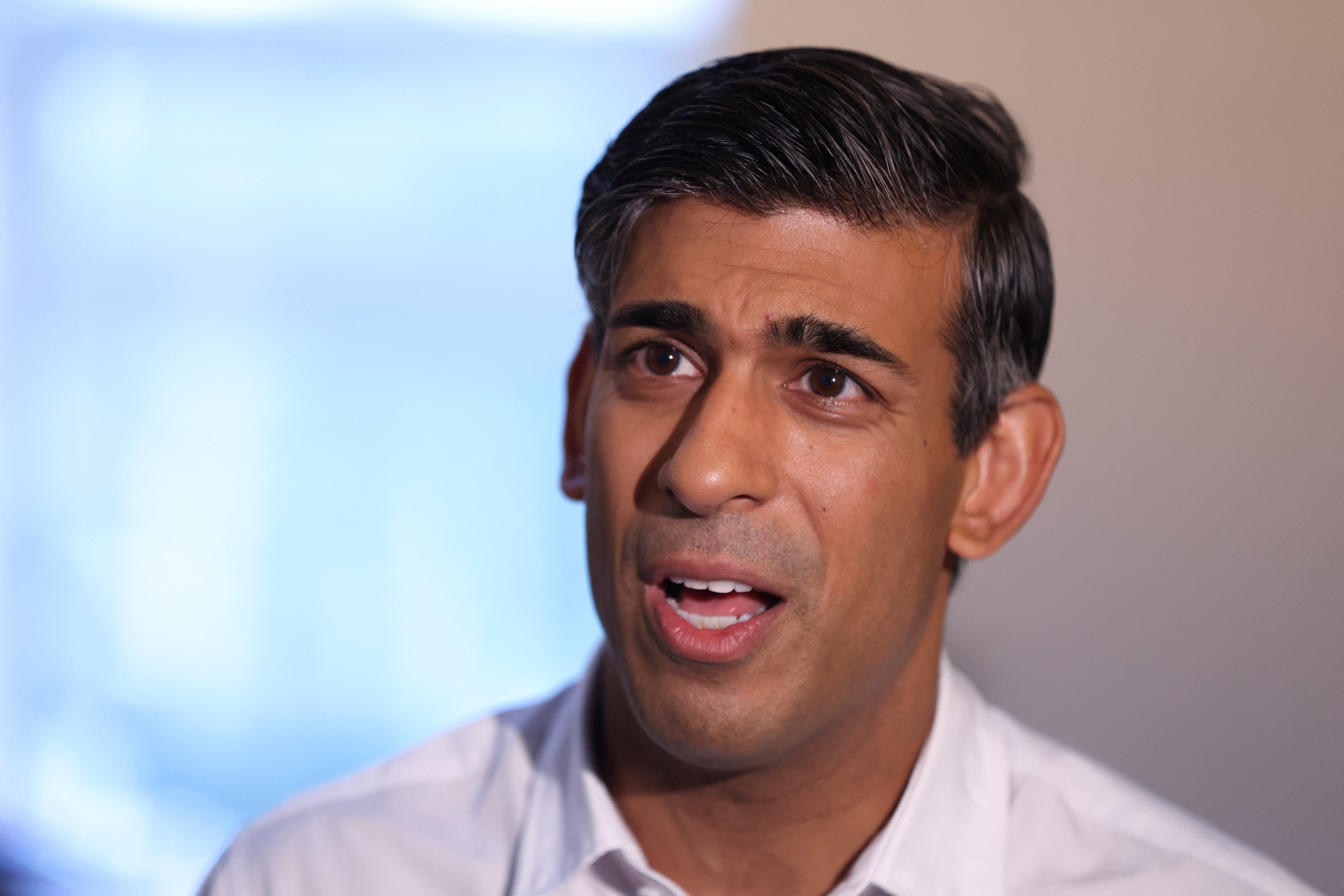

The liberal Tories drew two “red lines” Rishi Sunak should not cross: a firm commitment to net zero, and remaining in the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). In the past 10 days, Sunak has blown up their campaign, diluting some measures to achieve net zero and allowing Suella Braverman, the home secretary, to float the idea of leaving the ECHR.

So One Nation Tories are in a gloomy mood ahead of the party conference in Manchester starting on Sunday. They regard Sunak as a member of the “sensible right” and many of them voted for him in last year’s leadership contest. They view Jeremy Hunt, the chancellor, as “one of us.” But they fear Sunak is lurching to the right to appease his hardline MPs and to shore up the Tories’ core vote.

They fear it spells electoral disaster, as it will alienate under-50s and people living in the south. Indeed, the Onward think tank found that 49 per cent of 2019 Tory voters back net zero, with only a fifth opposed, but many want the government to help them to “go green.”

I’m told the liberal Tories are divided about what to do next. Some are so depressed about events they wonder whether the game is up for them inside the Tories and are starting to think the way forward might be to launch a new centre-right party. David Gauke, the respected former cabinet minister, hints at such an approach in a book of essays, The Case for the Centre Right, launched last night.

He says “the liberal centre right will face some stark choices” if it cannot halt the drift to the right in the “robust debate” over the Tories’ direction in the months and years ahead. He adds that “whatever happens with the Conservative Party, the UK needs a strong and powerful liberal centre right.” He argues that “the failures of the populist right” makes the case for a return to “openness, internationalism, moderation, prudence and integrity.”

Gauke stood as an independent at the 2019 election after being one of 21 Tories to lose the whip under Boris Johnson during the heated parliamentary debate on Brexit.

One unfortunate side effect of Brexit was to demolish the Tories’ broad church. Politics is worse off without it. Although there are still about 80 One Nation Tory MPs, they lack influence and, unlike their right-wing rivals, cheerleaders in the press. They fear that after a general election defeat next year, Tory grassroots members would ignore the lesson of the Liz Truss debacle and elect another right-winger such as Braverman as leader.

Some liberals share Gauke’s pessimism about their prospects inside the Tories. But others, such as David Lidington and Amber Rudd, are arguing against a breakaway, pointing out accurately that the first-past-the-post voting system is a huge barrier for new parties, as the Social Democratic Party discovered in the 1980s and ChangeUK did in 2019. These Tories conclude the lesson from Labour is that the centrists who decided to “stay and fight” when the left took control eventually regained power inside the party – under Neil Kinnock in 1983 and Keir Starmer in 2020.

But if, as looks likely, the right has a firm grip on the Tories after the next election, it is not impossible that some liberals decide they have nothing to lose by breaking away. On the face of it, they might not be alone: Dominic Cummings, Johnson’s former aide, has floated the idea of a start-up party taking a tougher line than the Tories on crime, security and immigration, and the ECHR. But there would be little space to outflank the Tories from the right if they become a hardline party in opposition.

Some liberal Tories see their best hope in this scenario as a hung parliament in which Ed Davey, the Liberal Democrat leader, demands the introduction of proportional representation as the price of supporting a minority Labour government. Only one problem: Keir Starmer’s one-time enthusiasm for electoral reform has cooled. If he does not win an overall majority, Starmer would probably tell the Lib Dems to choose between voting for Labour’s programme or allowing the Tories back in.

The absence of PR would probably leave a new liberal Tory party in the wilderness. Breaking up is hard to do; in politics, it rarely has a happy ending.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments