Tim Lott: Excuses, buck-passing, and the lost virtue of taking responsibility

Why does no one own up to their own mistakes any more?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

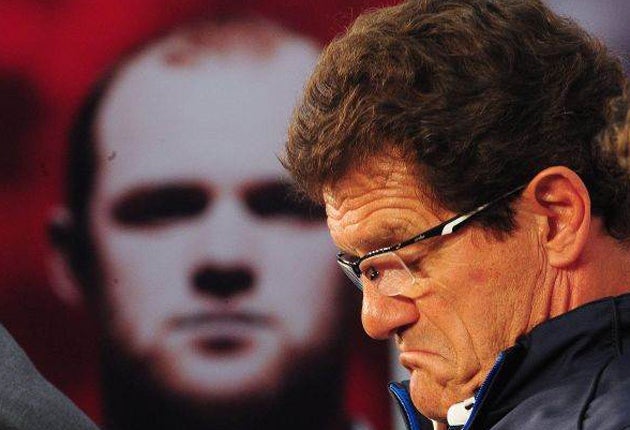

Your support makes all the difference.For the worst World Cup performance in memory, Fabio Capello blamed (at different times) the referee, the long season, and the new ball. He seemed singularly disinclined to blame himself. Likewise, Wayne Rooney complained about the fans, but anyway, it certainly wasn't his fault, and besides, he was tired.

Football is a rich source for improbable excuses – last year Sir Alex Ferguson attributed United's losing to Fulham on the inadequate size of the Craven Cottage dressing room. But football by no means holds the monopoly. On the tennis court, a grumpy Roger Federer blamed his bad back as he crashed out of Wimbledon, and in politics, as the Iraq inquiry unfolded, Tony Blair continued not to take any blame whatsoever for the grisly mess that was Iraq.

Being a bad loser and the failure to take responsibility for your actions are closely connected phenomena. I speak from experience – I can be a bad loser myself. I take no pride in reporting that a few weeks ago, I growled to my brother, after losing to him at tennis, "I was shit – but you were slightly less shit".

No, I agree, it wasn't very nice. But then, you've never played him (all feeble dolly shots and lobs down the middle, laced with slightly smug expressions). And he is my brother. Nobody, other than the Williams sisters, loses gracefully to a sibling.

These lame defences of my indefensible behaviour are perfect examples of excuses – which along with rationalisations, elisions, lies and blanket denials constitute the armoury of the serial responsibility-avoider. And that includes most of us in some context or other. It's a tendency deeply embedded in the soul. "Look what you made me do," has been the default position of the human since the world began.

After all, the two earliest and most enduring Christian myths are about the wilful avoidance of responsibility. Adam blamed his eating of the apple on Eve, while Eve blamed it on the serpent. And the serpent, no doubt, just smiled and gave God a knowing wink. One generation later, Cain was refusing to take the rap for murdering Abel with his dismissive reply to God's request as to Abel's whereabouts – "Am I my brother's keeper"? Like his dad, he just wouldn't take responsibility for what he had done.

The trend for ducking responsibility continues unabated. No longer do we blame it on a snake, or the stars, or the gods, or the portents – most of us, anyway – but whether it's the wrong kind of ball or the wrong kind of snow, we're still pretty keen on the whole game of "it wasn't me, honest".

Politicians are, obviously, particularly prone to the syndrome, simply because the stakes are so high. Richard Nixon explained away an 18-minute blank on the Watergate tapes by blaming it on his secretary for accidentally putting her foot on the erase button while she was answering the phone. Bill Clinton famously "did not have sex with that woman" and George Bush, after the disaster of Hurricane Katrina, justified his government's failure by saying, "I don't think anybody anticipated the breach of the levees."

Bush's avoidance of responsibility here was straightforward lying – a number of reports had long warned that the levees were not sufficiently secure. Clinton's was the pedant's defence against responsibility – "having sex" clearly means different things to different people. Likewise, civil servant Sir Robert Armstrong did not mislead the public by lying during the Spycatcher trial in 1986. He was simply "economical with the truth". A gift for verbal elision is the stock in trade of the professional blame-dodger.

More recently, more modestly, but equally entertainingly, there was Labour MP David Wright's Twitter message about the Conservatives, "You can put lipstick on a scum-sucking pig but it's still a scum-sucking pig". This was apparently down to "someone ... tinkering with his Twitter account". And on the other side of the benches, Conservative MP Stewart Jackson defended claiming expenses for his swimming pool as legitimate because "the pool came with the house and I needed to know how to run it".

Politicians ain't what they used to be, that's for sure. Once upon a time they would fall on their sword when they felt they – or their, crucially, their department – had failed. Memorably, James Callaghan resigned immediately after the pound devalued under Harold Wilson's government in 1967. It wasn't his personal fault, but as Chancellor it was his responsibility – hence he was honour-bound to go.

In stark contrast, Norman Lamont hung on as Chancellor blithely – or rather shamelessly – for seven months after Britain was forced out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992. That crisis was partly Lamont's fault, as well as his responsibility, but it made no difference. Political times had changed – now it was a question of surviving at all costs, or at least until you are about to be sacked anyway.

The concepts of "fault" and "responsibility" are woefully mixed up in both the private and the public mind. If Baby Peter dies on her watch, it is not Sharon Shoesmith's fault, but it is her responsibility which is why it is shameful that she did not resign when the facts of the case came out. If the England team put in their worst performance in World Cup history, that isn't Fabio Capello's fault – the fault is separated into multiplicitous strands – but it is his responsibility. You may resign either because of fault or because of responsibility – but few people do either, nowadays.

An excuse is a wonderfully tempting thing, though, even for ordinary human beings. The really good excuse is like an all-purpose suit of armour. Ideally, it will be unchallengeable on the grounds of taste or propriety. There's a great episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm in which the mother of Larry David's character dies. He's not close to her and he's not that upset, but he quickly finds out that whenever he messes up – as, being Larry, he does frequently – as soon as he uses the phrase "my mother just died", he is immediately forgiven. He consequently starts to use the excuse with recreational abandon – even getting good tables at sought-after restaurants because "my mother just died".

The reason why avoiding responsibility is so popular is obvious – there just aren't that many good motivations to own up. This applies in private life just as it does in public. What is a marriage, after all, but a series of attempts by either partner to avoid responsibility? And what is a naughty child's first weapon of defence other than "He [or she] started it".

How I long to hear those words "I'm sorry darling, it was my fault." But I never shall. I myself tend to eschew excuses, preferring to put my hand up – for all the good it does me. It wins me not a scintilla of mercy – because for my wife, there is no distinction between a good reason and an excuse. In fact, my wife always seems further infuriated that I haven't tried to come up with an excuse that she can then puncture with facts and liberal helpings of scorn.

The trouble with taking responsibility is that, in the end, there's just too little motivation for it. You lose face, or, if you're the manager of England, you lose money, the face being beyond salvation. There are people who believe that the only way to enjoy integrity as a human being is to face up to what you have done, at least internally, and ideally publicly, but they are in the minority. For most, the questions is not, "Is this down to me?" but "Can I get away with this?" Even if the answer to the latter question is no, the temptation to duck responsibility can still be irresistible. We just hate 'fessing up.

Again, the Bible is the best source to explain this. It identifies the disease – that the fundamental human failing is to duck responsibility – and it also identifies the source of the disease, which is spiritual pride. We cannot face the consequences of what we do, not simply because it might cost us money or prestige, but because we lack humility. And thus we sacrifice our chance of dignity, or, if you are of a religious mindset, the love of God.

The fact is, there is no real shame in failing. The shame is in dissembling. All of us fail at something at some level more or less every day. If Capello and Rooney and Clinton and Blair and all the rest of them had held their hands up and said, "We're human. And we screwed up", they could have a lot to lose. But I suspect they would also gain something that, although intangible and apparent only to themselves, might be truly valuable.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments