Terence Blacker: Standing up for bad language

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The much-loved author Alexander McCall Smith is concerned about moral pollution. He believes that swearing blights society, representing "casual aggression" and, under certain circumstances, "a form of sexual intrusion".

Coincidentally, what McCall Smith calls "strong language" has been on my mind, too, although it is fair to say we take a slightly different tack on the subject. Watching the excellent new BBC3 comedy series Him and Her, I realised that my enjoyment of the programme owed much to a sense of liberation that it offered. Here was a sitcom which treated me as an adult, rather than as someone of acute sensitivity, who could be watching the programme at 10.30pm in the company of small, impressionable children.

The episode I saw contained eye-wateringly rude lavatorial jokes, regular references to casual sex and plenty of swearing. It was like being back in the early, glory days of Channel 4.

There is a greater pollutant than swearing, and that is prissiness. One of the effects of the rumbling debate about the right – or otherwise – to cause offence has been a general loss of nerve about opinions or words which might possibly stir up our ever-vigilant moral guardians. Now, when an episode of Mad Men is shown at 10pm on BBC4, a moral health warning is included on the on-screen billing: the programme, we are solemnly warned, contains adult themes. When a rock concert is broadcast in which a swear word has been uttered, there will be a warning about strong language.

Where did this new primness come from? Why is it that, even after the watershed, there is a general assumption that children and the easily offended will be watching and that it is they, not the rest of the adult population, who should dictate the moral agenda? A similar nervousness is to be found in the written press and even, embarrassingly, in fiction.

Bad language is good in the right context. It is part of a writer's armoury, and the decision to use it has absolutely nothing to do with sloppiness or laziness. Surely it hardly needs saying that the novels of Philip Roth, Martin Amis, James Kelman, Bret Easton Ellis and countless others would lose bounce, daring and aggression without carefully deployed expletives. Without its joyous, childish swearing, South Park would be incomparably less funny and subversive. The main joke of The Thick of It is Malcolm Tucker's creative genius for foul-mouthed abuse.

The new fear of "bad language" indicates a wider conformity. Swearing can often represent defiance and individuality. Listen, for example, to the collection of First World War canteen songs put together in 1995 by Tim Healey on a CD called Carry On, Lads, and somehow it is difficult to see the familiar expletives, when written and sung by servicemen fighting for their country, as a moral pollutant. There the strong language – from "Fuck 'em all, fuck 'em all, the long and the short and the tall" to "Ain't the Airforce Fuckin' Awful" – represents strength.

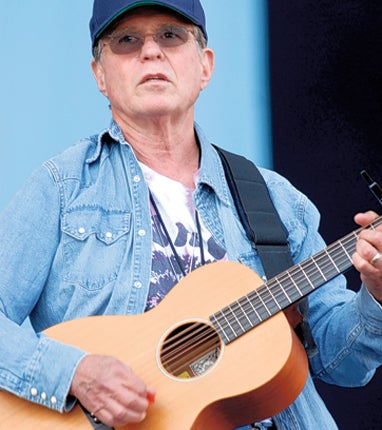

Bad language may even denote a society which is in robust shape. In the 1960s, when many liberal attitudes we take for granted were earned, swearing became something of a revolutionary act. Before he sang his great anti-war song "Fixin' to Die Rag", Country Joe McDonald would ask his audiences to "give me an F, give me a U, give me a C, give me a K".

The best writers of the alternative culture – Terry Southern, William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg – saw that liberation begins with language. One of the leading magazines of the time was called Screw; another, set up by Ed Sanders and the recently-deceased Tuli Kupferberg, went under the title of Fuck You; a Magazine of the Arts.

The squaddies of the Second World War and the hippies of the Sixties had little in common but both used indecorous language as an expression of their own bloody-minded independence. We need a bit of that spirit now. Give me an F, give me a U...

Having the best of times – unless you're getting on a bit

There is something distinctly odd about the BBC's recent enthusiasm for the old. In a Newsnight investigation into the retirement years, there was worthy talk about the dangers of the old being portrayed in the media in an unthinking, hackneyed fashion. A few moments later, their correspondent was reporting, in the semi-facetious manner the programme often likes to adopt, from a thé-dansant in Yorkshire where ancient pensioners were shuffling about the dance-floor.

The same uncertain tone – sympathetic but slightly amused – is to be found in the reality show The Young Ones. It is there in the title, in the incidental music and in the comments of the middle-aged experts who are watching a group of celebrity old codgers who have been locked away in a house together.

The idea is sound enough. Old people, the programme will doubtless show, become less helpless and dependant when their minds and bodies are kept active, but the nigglingly patronising tone is not unlike that used in programmes about badly-behaved teenagers. It is as if the experts who are still in active adult life prefer to see those much younger or much older than themselves in terms of an easy, reassuring cliché.

The anthems in the pews, consigned to the terraces

As if the Catholic Church were not causing enough controversy, the Archbishop of Melbourne has banned the playing of inappropriately secular music at funerals. Australians have apparently developed a liking for a singalong as they bid farewell to a loved one. Among the most popular musical favourites, up there with those old favourites "My Way" and "The Wind Beneath My Wings", are several Aussie Rules Football anthems.

The archbishop has had enough of all this. "In planning the liturgy, the celebrant should moderate any tendency to turn the funeral into a secular celebration of the life," he decreed. Sporting songs, romantic ballads and pop songs have been proscribed, as has any tune which might intensify grief. It is a brave position to take, since a modern funeral, if it is not actively celebratory, tends to encourage feelings to be on full display. Already priests, anxious not to seem out of touch, are suggesting that football anthems might be sung on the way into church.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments