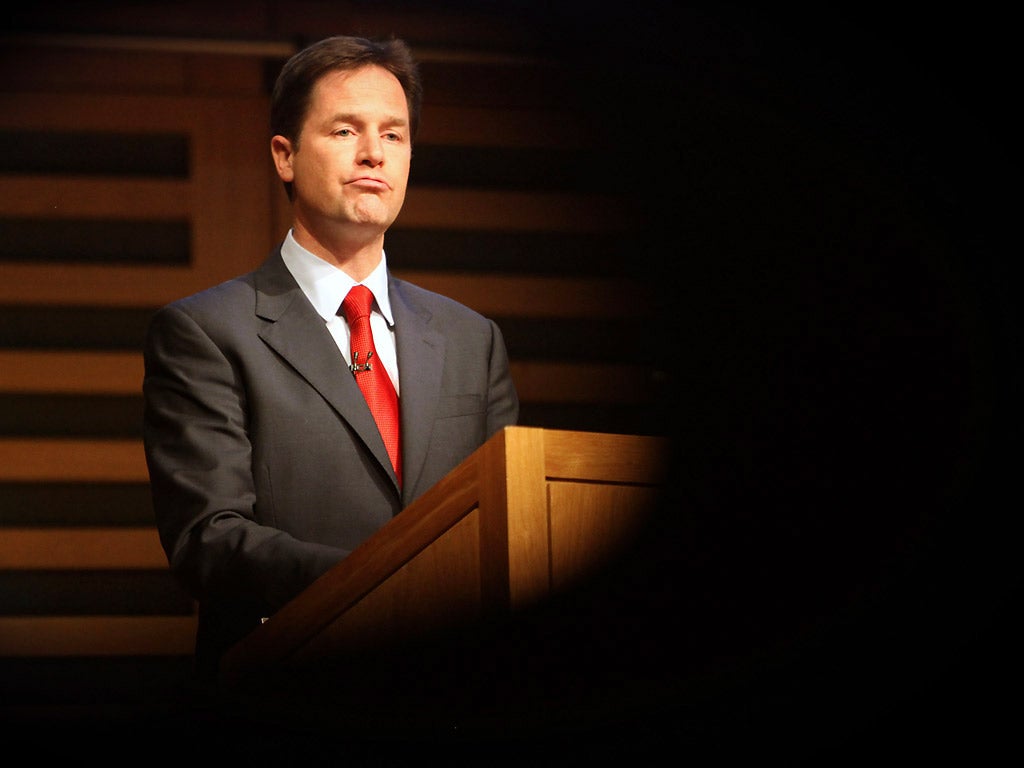

Terence Blacker: Clegg a frustrated writer? He's more of a frustrated politician, surely

What do the Deputy Prime Minister's Literary pretensions

tell us about him? Also: thoughts on the late Ray Bradbury

The effortlessly irritating Nick Clegg has done it again. As a politician of the muddled middle, he is caught awkwardly between a reluctant support of big business and an uncertain, watered-down brand of statism. In his private life, he again took the middle way by owning up to precisely the number of sexual encounters (30) which would simultaneously annoy prudes while disappointing freer, more liberal spirits as a rather feeble show under the circumstances.

Now Clegg, the would-be writer, has stepped forward, as tentative and unsatisfactory as Clegg, the politician, and Clegg, the ladies' man. Among the décor hints and summer pudding recipes of the latest issue of Easy Living, the Deputy Prime Minister has revealed that he would like to write a novel one day. "I find writing very therapeutic," he says. "I would love to emulate the style of one of my favourite writers, JM Coetzee, although I don't think I ever could."

During his twenties, he had embarked on a novel inspired by another of his literary idols. Gabriel Garcia Márquez, but had abandoned it after 120 "shockingly bad" pages. These days, he stills reads fiction "religiously" before going to sleep.

These are not unusual fantasies, and are normally articulated at the end of a boozy dinner-party, at a book club or after an inspiring talk at a literary festival. In this age of self-obsession, writing fiction has acquired a surprising new social cachet. The ambition to write a novel suggests an emotional hinterland. If realised, it can also, by some happy miracle, have a therapeutic effect, making one a kinder, saner, more contented person.

The dream of finding fulfilment through writing, cheerfully encouraged by the vast creative writing industry, is now so embedded in our culture that it is difficult to shift. The briefest glance at the kindness, sanity and contentment of those who write for a living may cast some doubt on the effectiveness of writing as therapy, yet people continue to write in the hope, presumably, of becoming as generous-spirited as VS Naipaul, as sensitive as Jeffrey Archer, as humble as Martin Amis.

When the would-be writer eventually writes, it is usually in the manner of a literary favourite – Garcia Márquez, say, or JM Coetzee – and the novel tends to peter out when the fun becomes hard work, which is usually around page 120. A bit of time is wasted, but a useful lesson learned, and no harm done.

In Clegg's case, though, the dream is terribly sad. It points up why he is never that convincing as a political leader. The impulse to invent fictional worlds comes from a need to re-order experience, to imagine circumstances and characters away from the mess of real life.

Press reports have described Clegg as "a frustrated novelist", but this interview suggests that the opposite is the problem. It is politics where his frustration lies. In government, his position shifts, just as the plot of a novel might change as it is being written. The characters in his political life often "take over"; he is never entirely in control of his material.

It is wrong to suggest that Clegg's favourite authors – Samuel Beckett is usually listed, but not in Easy Living – suggest literary pretentiousness. His enthusiasm seems genuine enough. What they have in common is that they create their own particular and peculiar fiction, in which the detailed and mundane have no place. Politicians who have written novels, from Disraeli through to Edwina Currie, have tended to set their stories in a recognisable world. For them, fiction was a sideshow to their political careers. Clegg's imagined literary life is different; the novel he would like to write is ambitious, pared down, stylish. Since he says he does not care to read about politics, he would be unlikely to write about it. He is dreaming of escape from the reality in which he finds himself. His fantasy reveals more about himself than he thinks.

Ray Bradbury's predictive text

Satnavs, it has been revealed, are dangerous. Not only can they direct you into a river or up a private drive, but the instructions they give can addle and overload the brain, disabling human faculties that are really quite important while driving – vision, for example, and commonsense.

Ray Bradbury, who died this week, would not have been surprised by these findings. "What is there about such 'conveniences' that makes them so temptingly convenient?" he asked in his astonishingly prescient short story The Murderer.

Its central character has been sent mad by the sound, inescapable throughout the day, of advertisements, muzak, inter-office communications, talking household appliances and incessant calls on his radio wristwatch from his wife and friends.

"The very idea of these things, the practical uses, was wonderful. They were almost toys, to be played with, but the people got too involved, went too far, and got caught up in a pattern of social behaviour and couldn't get out, couldn't admit they were in, even."

Those words were written in 1953.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks