Rupert Cornwell: Unlike our boat race, US college sport is big business

Out of America: University games are meant to be strictly amateur – but there are millions of dollars at stake

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Both, on their respective sides of the Atlantic, are national rites of spring. Both are sporting events, involving well-known universities. But there the similarities end. Britain yesterday celebrated the 157th rowing of that faintly dotty Corinthian throwback known as the Boat Race. America meanwhile is gripped by the month-long extravaganza known as "March Madness".

Never heard of it? Don't worry, outside the 50 states of this great union (and a few people in Canada), nobody has. It is the annual men's college basketball tournament, now at its quarter-final stage, and whose final takes place in Houston a week tomorrow. You may, like me, find basketball a rather tedious exercise, where one team runs down the court and a very tall man scores, and then the other team immediately runs to the opposite end and another very tall man plops the ball into the basket. But that's beside the point. March Madness is the ultimate example of that multibillion-dollar, uniquely American institution known as college sports.

In Britain, the phenomenon – insofar as it ever existed – has today shrunk to the annual contest between Oxford and Cambridge over a stretch of the Thames. Here though, at least in its two principal manifestations of basketball and American football, college sports is a money-spinning religion, and growing more lucrative and commanding a more devoted following with each passing year.

The tournament now features a record 68 teams. The organisation that runs it, the National Collegiate Athletic Association or NCAA, has just signed a 14-year TV deal worth $10.8bn. The audience for the March Madness round-of-16 was 14 per cent higher this year than in 2010, while the final will probably be watched by more people than baseball's World Series or even the best-of-seven NBA championship in June, the showcase of US basketball and the very pinnacle of the sport.

In Las Vegas, more bets will be placed on the final in Houston than on any other American sporting event barring football's Super Bowl. It's amazing (to a foreigner at least) but true, that where football and basketball are concerned, college sport in the US is as big a deal – some would say an even bigger deal – than the professional major leagues. More remarkable still, this new surge in popularity comes at a moment when experts complain the players are not as good as they used to be, largely because the best ones either curtail their time at university or skip it entirely, to partake of the riches of the NBA.

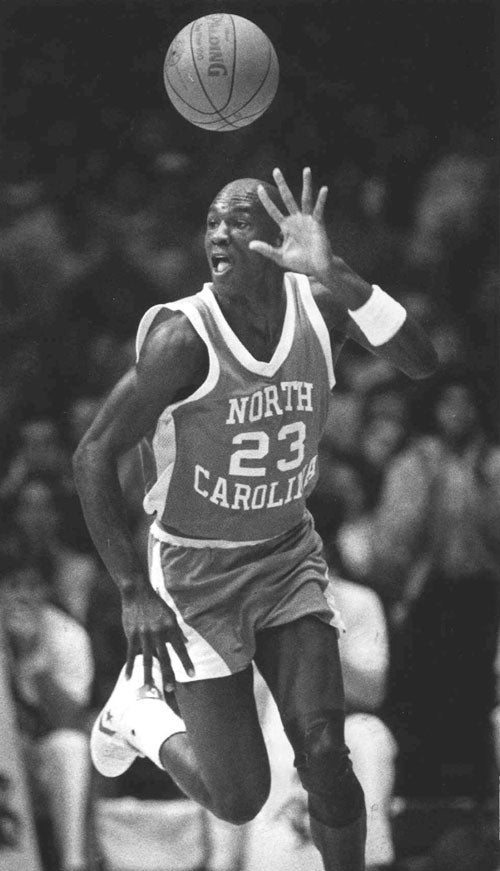

This lack of stars has undoubtedly tended to make March Madness more even and unpredictable, and thus more exciting. But it is safe to say that nothing that happens in Houston will resonate down the years as did the winning shot for the University of North Carolina in the championship game of 1982, made by a certain gangly freshman called Michael Jordan.

All, however, is not well in this seeming financial paradise. The Boat Race may be an anachronism, innocent fun tarred only by the odd grumble that some postgraduate participants may (perish the thought) have been awarded their university place morefor their rowing skill than their academic prowess. In US college sports, however, that is the norm.

On the basketball court or the football field, all must be snow-white amateur probity, the NCAA insists. Its athletes perform solely for love of the game, it maintains, and any payments to them are illegal. Payment, though, can take many forms: backhanders, lavish perks and inducements, and of course all-expenses-paid sports scholarships. And they must chart their unsullied paths through an ocean of money and commercialism that surrounds them.

At some American seats of learning, sports are more important than any academic discipline. Athletic success brings fame, money and prestige – which is why the football or basketball coach can be the most important individual on campus.

Success breeds money. Millions watch on TV, so the sports equipment makers pay extra millions for teams to wear their shoes or jerseys. The University of Michigan reportedly received a $6m (£3.75m) signing bonus from Adidas, merely for switching from Nike. Then there's merchandise revenue. Think Manchester United team shirts and you get the idea. But things may be spinning out of control. A recent study found that spending per athlete at some big sports colleges was up to 10 times more than the outlay on education per student – at a time when recession has put even greater financial pressure on universities.

Since 1989, the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics has been trying to reform college sport, recommending among other things that an NCAA team should only be eligible for a tournament if at least 50 per cent of the players were on course to graduate. By one reckoning 10 of this year's 68 qualifiers would have been ruled out. The commission's message is sobering. If the current business model of college sport continues, it warns, the result could be "permanent and untenable competition between academics and athletics" and "a loss of credibility not just for inter-collegiate sports but for higher education itself." At least the dear old Boat Race doesn't cause problems like that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments