Rupert Cornwell: The mysterious case of the New Jersey Five

Out of America: After acquittal of prime suspect, fate of teenage boys who vanished in 1978 is as unclear as ever

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Perhaps only one thing is sadder than a mystery without an end – at least when the mystery in question surrounds five teenagers who, one sweltering summer's day 33 years ago, simply disappeared from the face of the earth. And that is when the mystery seems about to be resolved, only for the explanation to crumble, like dust through the fingers, into nothing.

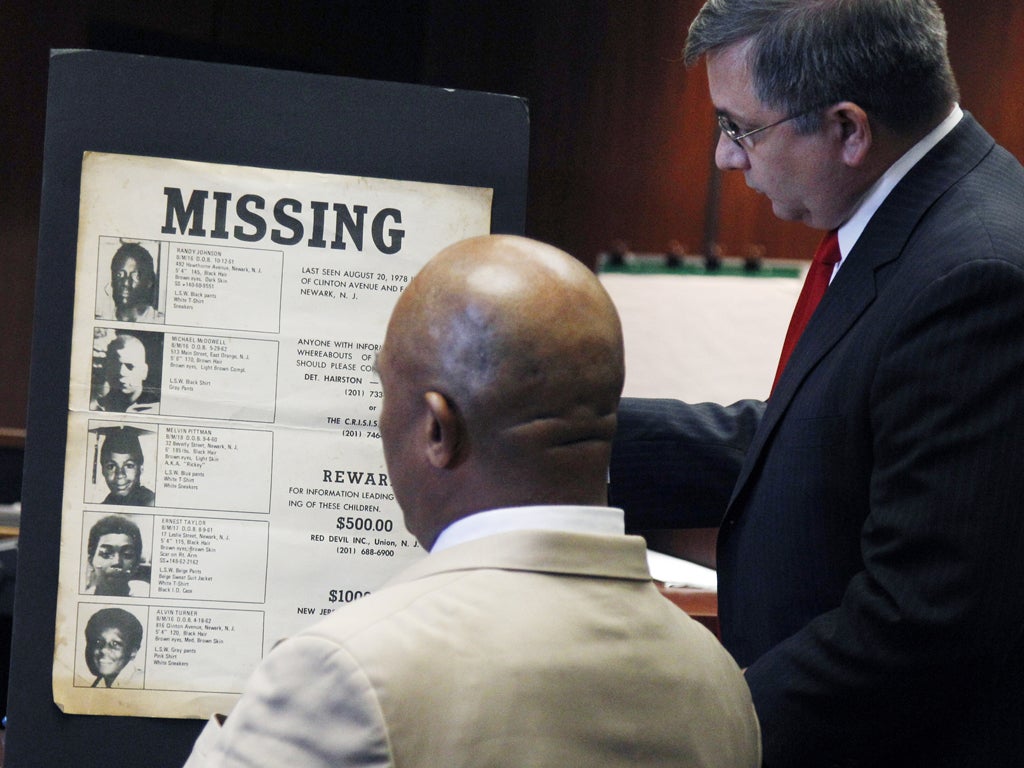

On the afternoon of 20 August 1978, Ernest Taylor, Randy Johnson, Michael McDowell, Melvin Pittman and Alvin Turner played a game of basketball in a park in Newark, New Jersey. They went home for supper before going out again, to earn a few dollars doing some work for a local odd-job man. They were never seen again.

Last Wednesday, Lee Anthony Evans, the former odd-job man, was acquitted in a Newark court on charges of murdering the five 16- and 17-year-olds who would be approaching 50 today. In between those dates lies one of the most haunting crime stories that could be imagined. If, that is, a crime were committed at all.

From the outset, the investigation naturally focused on Mr Evans, the last person to be seen with the boys in what police initially treated as a missing persons case. But he insisted he was innocent, continued to go about his business and made no attempt to leave the area. He even passed a lie-detector test.

At that point the trail went cold, and small wonder. Back then, Newark was an industrial city fallen on bad times, with poverty and crime rates among the highest in the US. The police had more than enough proven murder and mayhem to deal with; no one paid much attention to the fact that a long-vacant house in a decaying neighbourhood had caught fire that same night of 20 August and burnt to the ground. There was even talk the missing boys had perished with the infamous Jim Jones in his Peoples Temple in Guyana later that year.

But the strange tale never ceased to nag Newark's police department – how could five kids just have vanished into thin air? Twice investigators even went so far as to call in psychics, who suggested that the bodies had been hidden in rubbish tips near Newark airport. The sites were searched, but to no avail.

In 2008, however, a seemingly decisive breakthrough finally arrived. A cousin of Mr Evans named Philander Hampton told police the boys had indeed been murdered. He had been involved, Mr Hampton said, but the crime had been organised and carried out by Mr Evans. In March 2010, the pair were arrested and charged. "The mystery," the county prosecutor boasted, "has now been solved."

Mr Evans protested his innocence as vehemently as ever and was released on bail. But Mr Hampton made a plea deal, admitting guilt and agreeing to testify against his cousin in return for a shortened 10-year sentence and $15,000 in "relocation money".

His story of what happened was horrific. Mr Evans, allegedly, had murdered the boys to punish them for stealing 1lb of marijuana. On that long-ago August evening, he had picked them up in his truck and taken them to an abandoned house where his cousin was waiting. With his help, Mr Evans forced the five into a tiny closet and sealed it shut with a hammer and a single long nail. Then he doused the room with petrol and set it ablaze, incinerating his victims. The problem was the absence of DNA and other physical evidence, and of any other eyewitness at the scene. A smart new house now stands on the site, but police used ground-penetrating radar and found absolutely no trace of the victims, not even a tooth or bone fragment. The prosecution case rested entirely on Mr Hampton's word.

He was not the most convincing of witnesses. For one thing, he had served 10 years for robbery, had a record of heroin use and admitted selling drugs from the building where the teenagers were supposedly burnt alive. Nor was his account entirely convincing. Mr Evans is big, hulking man – but could a single nail really have held back five desperate boys? Could they all have been crammed into a 4ft by 2ft closet?

At the trial, Mr Evans, acting as his own lawyer, performed well enough to win acquittal on all counts. Alas, acquittal, as every amateur jurist knows, does not necessarily signify innocence, merely a reasonable doubt of guilt. Mr Evans himself was anything but exultant at the outcome, aware that his own reputation will be for ever tarnished. "When you smash something up," he declared afterwards, "you can't put it back together."

We may criticise the process that led to Wednesday's verdict, the paucity of the evidence and the use of a plea-bargain system that on occasion positively invites perjury. Ultimately, though, there's no special moral to this story, just an overwhelming emptiness and sadness.

In a purely criminal sense, the matter is closed; unless unsuspected forensic evidence is miraculously unearthed, there will be no new investigation. But for the families of the disappeared, there is no closure. For the most part, they believe Mr Evans is another OJ Simpson, a guilty man walking free. As with OJ, there is talk of bringing a civil suit for wrongful death, and, given that the standards of proof required are less than in a criminal trial, such a suit might well succeed.

In reality, though, we are back to square one. We do not even know if it is a murder case at all – only that one sultry summer evening long ago, five teenagers with their lives ahead of them vanished as completely as if they had never been born.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

2Comments