Rupert Cornwell: Neighbours feud over drugs, guns, and immigration

Out of America: The killing of a Mexican boy by a US border guard highlights the tensions between the two nations

I was remembering the other day my first visit to Mexico, from the nondescript Arizona border town of Nogales. Where exactly was the frontier crossing, I asked, eager for adventure. "On the left," someone answered, "immediately after the Safeway parking lot."

That was more than 20 years ago, when relations between the US and its southern neighbour were, by historical standards, pretty smooth. Nonetheless, that "so what" reply still in part captures attitudes on this side of the border, of familiarity flavoured by a big dollop of condescension. But would things were as mundane today, and a supermarket parking lot could serve as a link between the two countries.

Consider last week's headlines in the American press. On Monday, a schoolboy was killed by a bullet (or bullets, the exact circumstances are as yet unclear) fired by a US border patrol agent across the Rio Grande river which divides city of El Paso, Texas from Ciudad Juarez in Mexico.

The shooting took place after some young Mexicans attempted to cross into the US illegally. Foiled, they apparently started throwing rocks at the agent. He fired back in self-defence, killing the 14-year-old boy – who by all accounts never left Mexican soil and had nothing to do with the incident. But it was the second such death on the border in a couple of weeks. Understandably outraged, the Mexican authorities condemned the shooting, accusing the Americans of acting like trigger-happy cowboys.

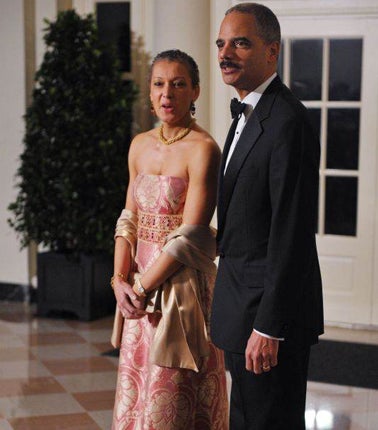

A couple of days later the stage switched to Washington, where Attorney General Eric Holder, America's top law enforcement official, announced to much fanfare that the FBI had arrested more than 2,200 people during a two year crackdown here on the Mexican drug cartels, that also netted 74 tons in confiscated illegal narcotics.

The public reaction to these separate yet related events was no less telling. The killing of the boy elicited sadness, though not really surprise. But the news of the mass arrests drew only a fatalistic shrug; could yet another police dragnet make any difference to the issue that above all others now defines relations between the US and Mexico.

It wasn't supposed to be like that. Back in 1993, the two countries, along with Canada, signed Nafta, the free trade agreement that was hailed as the dawn of a North American common market. The Canada-US part was always going to be easy enough; the tricky bit was the US-Mexico; and so it has proved.

Geography made the pair rivals from the moment they achieved independence from the European colonial powers, in 1776 and 1819 respectively. Nowhere else on the planet did the first world and the third world collide as along the 2,000 mile frontier between the US and Mexico. Never has it been a match-up of equals. America is five times larger by total land area, three times as populous and 12 times as rich.

In meteorology, such collisions between warm and cold air masses cause great storms. So it is that comparable human storms have been generated by the collision at the US/Mexican border of two utterly different economic and political universes. As those news headlines demonstrate, there are two overlapping areas of turbulence. One is drugs, the other is illegal immigration.

In the case of the first, look no further than the website of The Los Angeles Times, the flagship newspaper of California. In its world affairs section, the site devotes a special heading to "Mexico Under Siege", as prominent as the headings "Afghanistan" and "Iraq" – hot wars where American troops are actually fighting and dying. Today though, the country on the other side of the Nogales parking lot is a war zone too, of scarcely less consequence to the US, and just as deadly.

Nafta has undoubtedly boosted orthodox trade between its partners. But alongside trade, clandestine and often violent businesses now flourish as well. Mexico stands astride surely the world's largest underground trade route, of illegal drugs from producing countries into the US, the largest consumer market for these drugs. But if the drugs, along with the crime that always accompanies them, flow north, money (an estimated $30bn-plus a year) and guns flow in the opposite direction. The US not only buys more drugs than anyone else; it also sells more guns than anyone. These guns have made Mexico's killing fields even bloodier.

Since 2007, over 23,000 people are believed to have died in its drug wars, and Ciudad Juarez alone, with a murder rate of 130 per 100,000 inhabitants, is now the most dangerous city on earth. Such is the violence, and the inability of the authorities to deal with it, that some US commentators argue that to all intents and purposes, Mexico is a failed state.

That is, of course, an exaggeration. Nonetheless, large numbers of its 111m inhabitants will do anything to leave. Of the estimated 500,000 people who immigrate illegally to the US each year, a majority are Mexicans. During an economic boom such an influx might be tolerable, but not in today's hard times. That's why Arizona has just passed a draconian immigration law – one that President Obama wants to overturn, but the vast majority of Americans heartily approve of – and that's why Mr Obama is sending 1,200 more National Guardsmen to defend the ever more fortified border.

But this initiative will surely fail, as others have failed before it. The laws of economic gravity cannot be denied. Unless the US loses its insatiable appetite for illegal drugs, and until Mexico's standard of living moves close to that of America, the frictions and tensions along the border will persist.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks