Richard Dawkins: Illness made Hitchens a symbol of the honesty and dignity of atheism

On 7 October, I recorded a long conversation with Christopher Hitchens in Houston, Texas, for the Christmas edition of New Statesman which I was guest-editing.

He looked frail, and his voice was no longer the familiar Richard Burton boom; but, though his body had clearly been diminished by the brutality of cancer, his mind and spirit had not. Just two months before his death, he was still shining his relentless light on uncomfortable truths, still speaking the unspeakable ("The way I put it is this: if you're writing about the history of the 1930s and the rise of totalitarianism, you can take out the word 'fascist', if you want, for Italy, Portugal, Spain, Czechoslovakia and Austria and replace it with 'extreme-right Catholic party'"), still leading the charge for human freedom and dignity ("The totalitarian, to me, is the enemy – the one that's absolute, the one that wants control over the inside of your head, not just your actions and your taxes. And the origins of that are theocratic, obviously. The beginning of that is the idea that there is a supreme leader, or infallible pope, or a chief rabbi, or whatever, who can ventriloquise the divine and tell us what to do") and still encouraging others to stand up fearlessly for truth and reason ("Stridency is the least you should muster ... It's the shame of your colleagues that they don't form ranks and say, 'Listen, we're going to defend our colleagues from these appalling and obfuscating elements'.").

The following day, I presented him with an award in my name at the Atheist Alliance International convention, and I can today derive a little comfort from having been able to tell him during the presentation that day how much he meant to those of us who shared his goals.

I told him that he was a man whose name would be joined, in the history of the atheist/secular movement, with those of Bertrand Russell, Robert Ingersoll, Thomas Paine, David Hume. What follows is based on my speech, now sadly turned into the past tense.

Christopher Hitchens was a writer and an orator with a matchless style, commanding a vocabulary and a range of literary and historical allusion far wider than anybody I know. He was a reader whose breadth of reading was simultaneously so deep and comprehensive as to deserve the slightly stuffy word "learned" – except that Christopher was the least stuffy learned person you could ever meet.

He was a debater who would kick the stuffing out of a hapless victim, yet did it with a grace that disarmed his opponent while simultaneously eviscerating him. He was emphatically not of the school that thinks the winner of a debate is he who shouts loudest. His opponents might have shouted and shrieked. Indeed they did. But Hitch didn't need to shout, for he could rely instead on his words, his polymathic store of facts and allusions, his commanding generalship of the field of discourse, and the forked lightning of his wit.

Christopher Hitchens was known as a man of the left. But he was too complex a thinker to be placed on a single left-right dimension. He was a one-off: unclassifiable. He might be described as a contrarian except that he specifically and correctly disavowed the title. He was uniquely placed in his own multidimensional space. You never knew what he would say about anything until you heard him say it, and when he did, he would say it so well, and back it up so fully, that if you wanted to argue against him you had better be on your guard.

He was recognised throughout the world as a leading public intellectual of our time. He wrote many books and countless articles. He was an intrepid traveller and a war reporter of signal valour. But he had a special place in the affections of atheists and secularists as the leading intellect and scholar of our movement. A formidable adversary to the pretentious,

the woolly-minded or the intellectually dishonest, he was a gently encouraging friend to the young, the diffident, and those tentatively feeling their way into the life of the freethinker and not certain where it would take them.

He inspired, energised and encouraged us. He had us cheering him on almost daily. He even begat a new word – the hitchslap. It wasn't just his intellect we admired: it was also his pugnacity, his spirit, his refusal to countenance ignoble compromise, his forthrightness, his indomitable spirit, his brutal honesty.

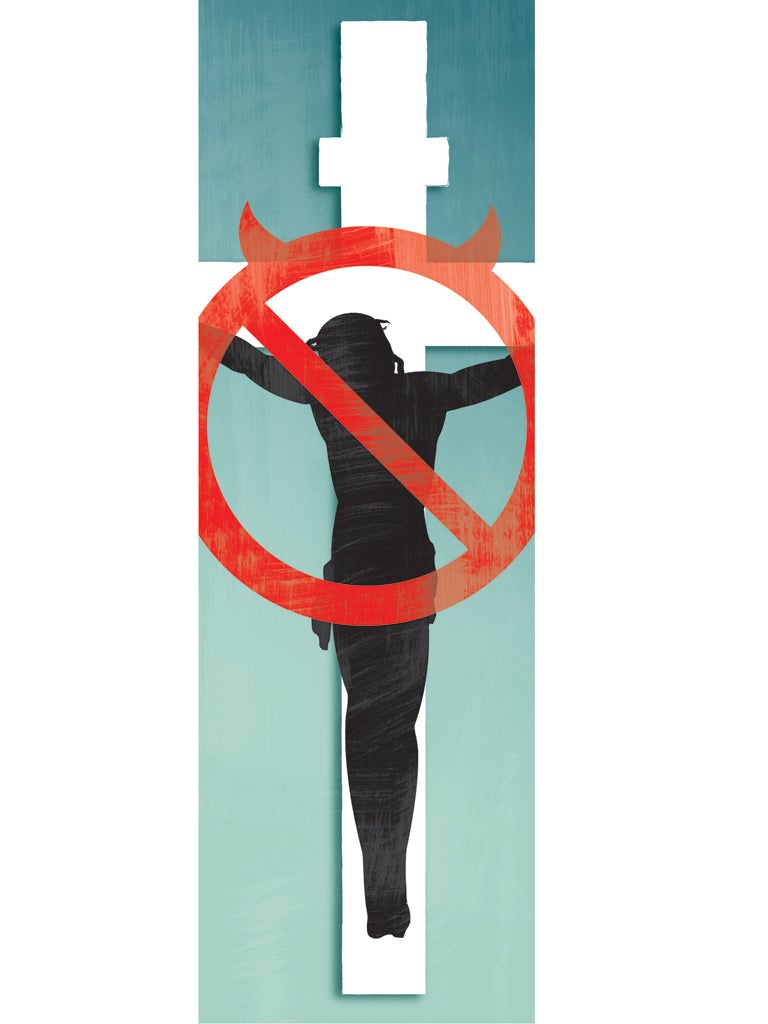

And in the very way he looked his illness in the eye, he embodied one part of the case against religion. Leave it to the religious to mewl and whimper at the feet of an imaginary deity in their fear of death; leave it to them to spend their lives in denial of its reality. Hitch looked it squarely in the eye: not denying it, not giving in to it, but facing up to it squarely and honestly and with a courage that inspires us all.

Before his illness, it was as an erudite author, essayist and sparkling, devastating speaker that this valiant horseman led the charge against the follies and lies of religion. During his illness he added another weapon to his armoury and ours – perhaps the most formidable and powerful weapon of all: his very character became an outstanding and unmistakable symbol of the honesty and dignity of atheism, as well as of the worth and dignity of the human being when not debased by the infantile babblings of religion.

Every day of his declining life he demonstrated the falsehood of that most squalid of Christian lies: that there are no atheists in foxholes. Hitch was in a foxhole, and he dealt with it with a courage, an honesty and a dignity that any of us would be, and should be, proud to be able to muster. And in the process, he showed himself to be even more deserving of our admiration, respect, and love.

Farewell, great voice. Great voice of reason, of humanity, of humour. Great voice against cant, against hypocrisy, against obscurantism and pretension, against all tyrants including God.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks