Paul Vallely: Maybe cowardice seems so despicable because we worry we'd also run away

Whatever human-nature defence may be offered for Captain Francesco Schettino, can we be sure that we'd do any better?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

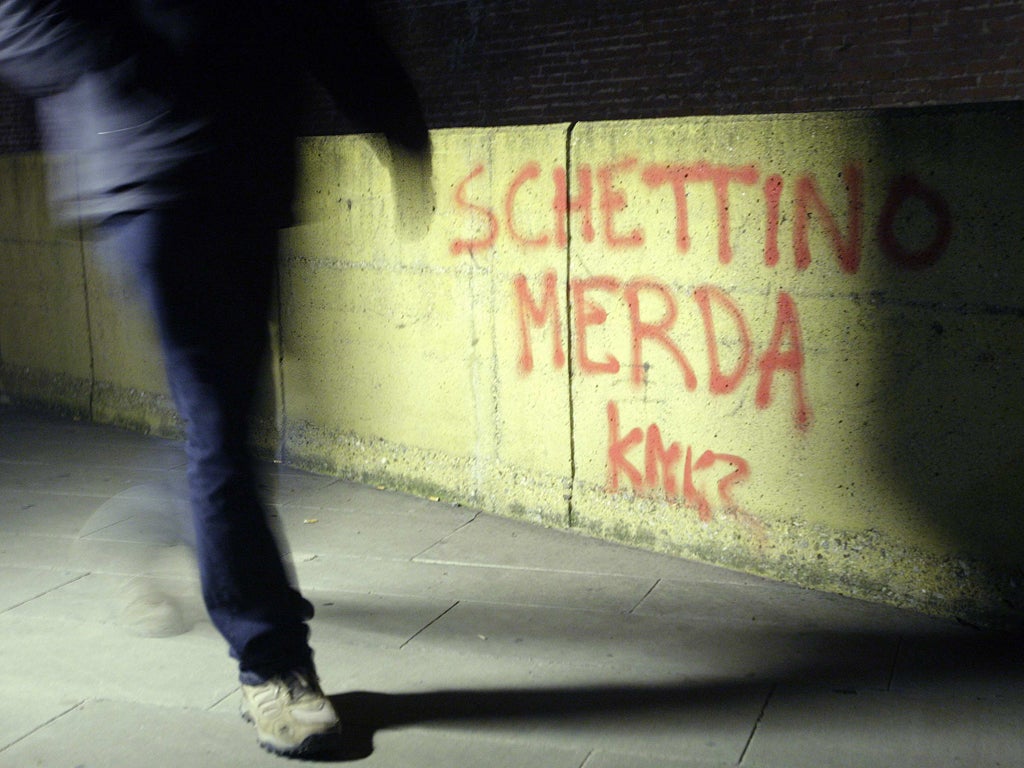

Your support makes all the difference.The world has rushed with glee to shower its scorn on Francesco Schettino, the man who ran aground the cruise liner Costa Concordia with the loss of at least 11 lives. His reckless behaviour looks set to see him charged with multiple manslaughter, abandoning a ship and causing a shipwreck. But what are we to make of the intense vilification of the mariner who has been variously called Captain Coward, the craven captain and the most hated man in Italy?

The judge handling the case has labelled his actions "inept, negligent and imprudent". Political pundits have seized upon him as a metaphor for Italy's self-inflicted economic woes. And the words screamed at him by the chief coastguard after Schettino left the liner before it had been fully evacuated – "Vada a bordo, cazzo!" (Get back on board, you prick) – have been emblazoned on T-shirts, made into a dance-disco remix and are being sold as a phone ringtone.

That concludes the case for the prosecution. But is there one for the defence?

Is human weakness a crime, one commentator tentatively asked. It's a line drawn from evolutionary psychology. What's wrong with cowardice, the argument goes. Isn't it just a pejorative way of describing the human survival instinct? Aren't we all hard-wired to save ourselves? If our ancestors hadn't run away and avoided getting killed we wouldn't be here in the first place, as Darwin might have said.

Why should we stigmatise a human quality that can't be overcome? Is there any more culpability in cowardice than there is credit in courage, a quality seemingly given to some individuals more than others? Isn't cowardice, as Ernest Hemingway put it, "simply a lack of ability to suspend functioning of the imagination". Discretion, as Shakespeare said, is the better part of valour.

Except, of course, that wasn't Shakespeare qua Shakespeare. He put the words in the mouth of that fat, foolish fraud Falstaff. The truth is that, if you want to follow Darwinian logic, we don't survive as individuals; we survive as a species. And, as Shakespeare also shows, altruism too is wired into us, and in a more profoundly mysterious way. Greater love hath no man, and all that.

But there is an unpleasant side to that social dimension. That was clear from the White Feather movement during the First World War when a group of bumptious busybody women, at the behest of a British admiral, handed out feathers as symbols of cowardice to any man on the street not wearing a military uniform.

Some of the victims dismissed it with humour. The conscientious objector Fenner Brockway claimed that he'd been given so many white feathers he had enough to make a fan. But others were brow-beaten into enlisting when they were not fit or had other responsibilities. The government became so alarmed at the pressure being put on public servants that it issued them with "King and Country" lapel badges to show they were already serving in the war effort.

The mob mentality in such bullying appears at work in the Schettino case. Armchair accusers are eager to point the finger in a situation in which they can never have been tested. Perhaps their disdain disguises a deeper anxiety that they might have been found wanting in such a circumstance. There, but for the grace of God... though God, in his own way, has been rather big on such scapegoating. The Book of Revelation puts cowards alongside murderers, sorcerers, idolaters, adulterers and liars as most detestable.

Yet the real opposite of courage in our society is not cowardice but conformity. The Costa Concordia case plays to a range of handy stereotypes. Schettino was a flash Italian who "handles his ships as if he is driving a Ferrari". When danger beckoned he ran away – that wartime joke about Italian tanks having one forward gear and five reverse reverberates in Italy, too – Francesco Merlo wrote in La Repubblica: "the notion of running away is part of our history, and nails the Italian character". Rather than "women and children first", for Schettino, one wag said, it was more a case of "Ciao, baby."

Yet all these things are culturally specific. "Women and children first" is, historically, a recent invention. It goes back only to 1852 when the British troopship HMS Birkenhead sank off South Africa. The 480 men on board were ordered to stand back while the wives and children climbed into the lifeboat. A Rudyard Kipling poem immortalised the ideal as the "Birkenhead drill". But the phrase is most associated with the Titanic.

That sinking continues to resonate loudly in the British psyche, especially in this centenary year of the 1912 disaster. As the "unsinkable" liner slipped beneath the icy waves, three quarters of the women on board were saved as were half of the children, but only a bare fifth of the men. It was the high point of a Victorian idealisation of British manhood which lauded classic masculine qualities of physical strength, courage and stoicism. They were virtues of Victorian chivalry on which an empire had been built. Yet this very empire was slipping away, along with the opulence and privilege that the Titanic symbolised, which was blown apart by the Great War.

But while it lasted it was a powerful ideal, replacing older notions that men came first, and those who violated it paid the price. The man responsible for building the Titanic, J Bruce Ismay, the managing director of the White Star Line, never lived down the shame of climbing into a lifeboat while women and children were still on board. To make matters worse, it was he who had vetoed the extra 48 lifeboats that would have saved nearly all the 1,500 people who died.

Ismay's hair apparently turned white overnight. Later his wife forbade mention of the word Titanic in his presence. He became a virtual recluse, hiring a whole compartment to travel on trains, demonstrating what would now be called post-traumatic shock disorder.

But none of that saved him from a savaging by the American and the British press, who labelled him one of the biggest cowards in history and renamed him "J Brute Ismay". He was ostracised in London society. "Mr Ismay cares for nobody but himself," declared one paper. "He passes through the most stupendous tragedy untouched and unmoved. He leaves his ship to sink with its powerless cargo of lives and does not care to lift his eyes."

In this post-feminist era the idea of giving precedence to women and children reveals an outdated notion of a weaker sex with children as the responsibility of women. Modern practice is for a ship's passengers to be assigned lifeboats according to their cabin numbers. On the Costa Concordia it was said that fathers refused to be parted from their families, on the grounds that a man's duty was to protect his own. The nuclear family is the new sacred norm.

In the end courage is, like so many other virtues, something which can be taught. Aristotle understood that. Doing the right thing when confronted with a big problem grows out of the habits cultivated when dealing with little problems, he says in the Nicomachean Ethics. Being moral is thus a very practical business. The army knows this. Its training is centred on building camaraderie of such intensity that men will risk their lives for one another. By contrast a civvy society, based on maximising consumer choice and personal preference, inculcates a worldview which is self-focused and self-absorbed.

Selfishness is the father of cowardice. Captain Schettino's tale of how he came to be in the lifeboat before his passengers is revealing. He was helping people, he said, when the ship suddenly listed and he tripped and fell into a lifeboat that coincidentally already held two of his top officers, including his second-in-command. It is a story that could only be told by someone who lacked the courage to face his own failings. "The coward is a despairing sort of person," said Aristotle, "for he fears everything."

Anyone can panic. The test is whether, when we have recollected our senses, we go on to do the right thing. Francesco Schettino was told by the chief coastguard to get back on board his vessel. There were plenty of rescuers ashore. But a captain's knowledge of his ship is crucial in an emergency. Instead, Schettino rang for a taxi and abandoned the scene, leaving passengers to fend for themselves. Coward, on this occasion, does not seem the wrong word.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments